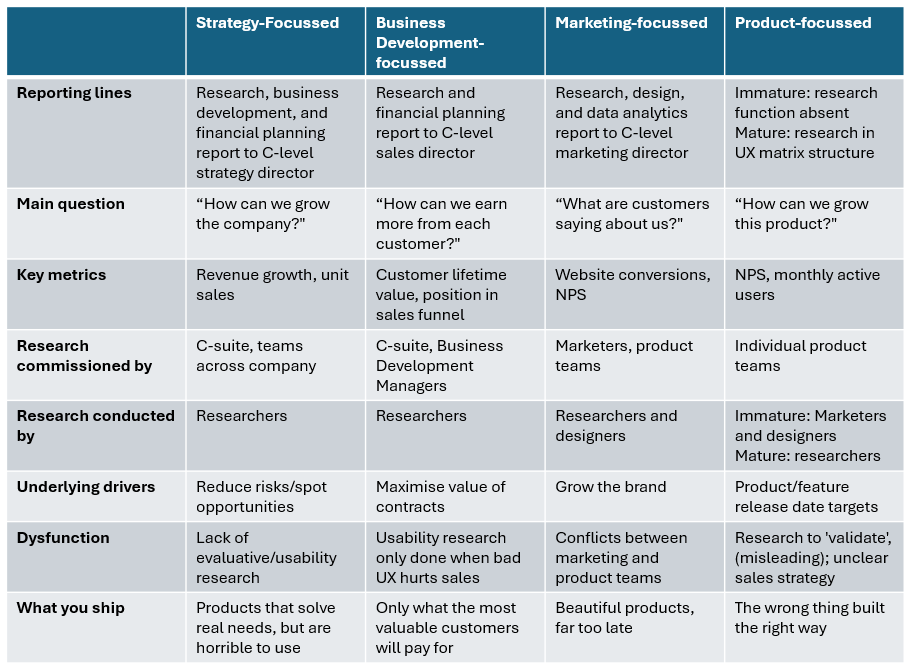

Most discussions on structure focus on centralised or matrix, but the departments in which those teams sit can make or break your product.

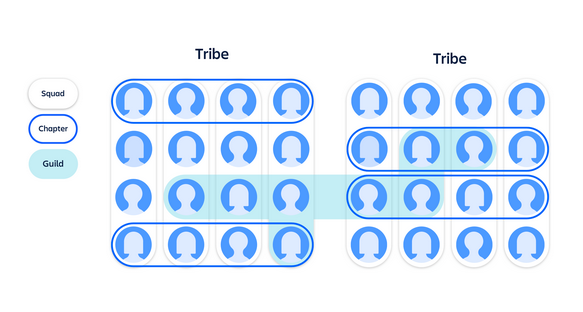

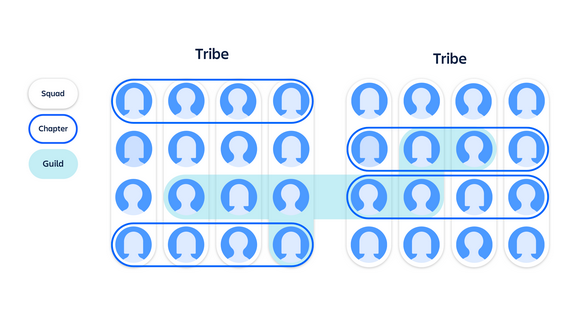

When the Spotify Model emerged in 2012, the world was entranced. Many companies tried and failed to replicate Spotify’s cultural success, mostly because they didn’t have Spotify’s people.

We learned that you can’t insert structure like a coin in a vending machine and expect culture to plop out, but it can make a surprising difference to your products.

Strategic focus

The result is products that solve real needs, but are lousy to use. You ship your structure.

The first time I worked on a survey, I was helping a colleague in another team. The market researcher put me to work coding open-ended survey responses into simple themes like “time,” “money,” and “price.”

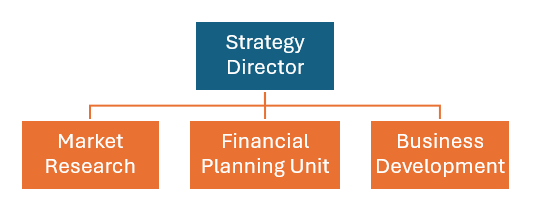

My regular boss was the C-level manager who wrote the business plan, whose office was next to the CEO, and the teams in her department included market research, a financial planning unit that crunched numbers, and business development.

In 2010, some years after I worked in this structure, Harvard Business Review described it as a Decision-Driven Organization:

“A corporation’s structure will produce better performance if and only if it improves the organization’s ability to make and execute key decisions better and faster than competitors. It may be that the strategic priority for your company is to become more innovative. In that case, the reorganization challenge is to structure the company so that its leaders can make decisions that produce more and better innovation over time.”

To make decisions for a market growth strategy, the director needed reliable information on trends and user needs, an understanding of the revenue impact of each decision, and a global view of the challenges and successes in every country.

In other words, the type of research gathered and value attributed to it was a direct result of the company structure.

You are probably wondering what role usability research played in all this, and the short answer is, it didn’t. The usability of a product did not obviously get between the director and answering the central question of a strategy-oriented structure: “How can we grow the business?”

The lack of demand for usability research stemmed from exactly the same source as the increased demand for discovery research.

Business development focus

The product you ship is designed around the needs of (only) your most lucrative customers.

Business development is related to sales, and UX design is related to pretty pictures. The latter might be part of it, but it’s a rich and rounded discipline.

“Business development is the process of planning for future growth by identifying new opportunities, forming partnerships, and adding value to a company. It involves understanding the target audience, market opportunities, and effective outreach channels to drive success.” — Investopedia

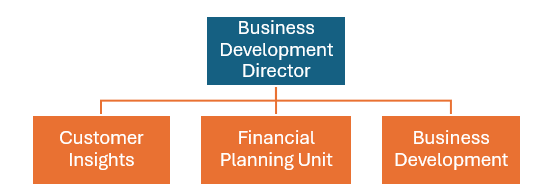

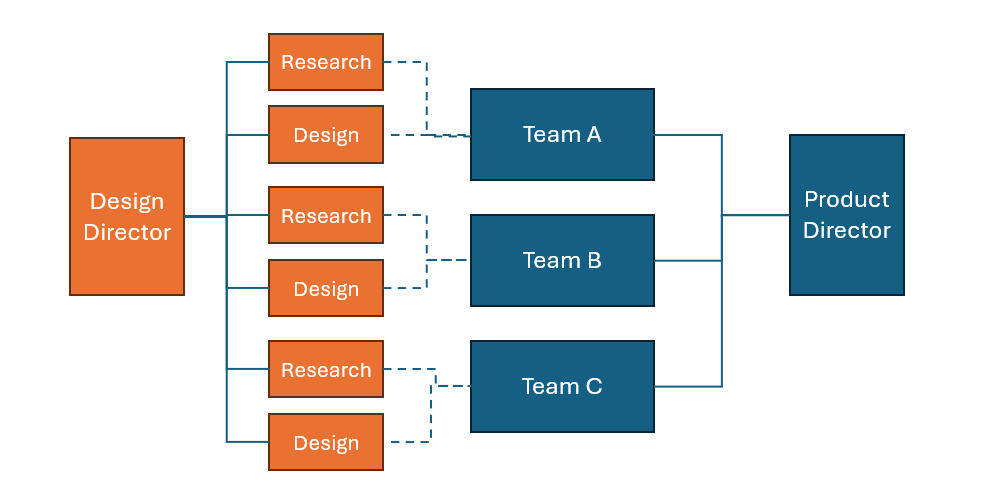

The structure I worked in looked like this:

The central question for the C-level director was “how can we we earn more from each customer?” and the core concept in business development is customer lifetime value.

“Customer lifetime value (CLV or CLTV) is a metric that indicates the total revenue a business can reasonably expect from a single customer account throughout the business relationship.” — HubSpot

To calculate it, you need to segment your audience and understand their purchasing habits: someone who goes to the cinema for the summer blockbusters has a very different spending profile than someone who goes twice every week.

You need to deeply understand the behaviours and drivers of each segment, so that the Business Development Managers can form long-term relationships with each client and pitch to them exactly the package that suits their needs.

While both strategy-focussed and business development-focussed organisations prioritise discovery work, the emphasis switches from macro to micro. You’ll see more demand for qualitative discovery research and usability research if UX flaws stand between a Business Development Managers and their sales target.

However, the BDM is not motivated to optimise the experience for every user. Another tenet of business development is the Pareto Principle: 20% of customers provide 80% of value, so don’t spend too much on people who spend too little.

Marketing focus

You ship beautiful products, far too late.

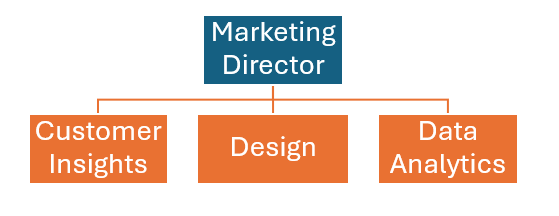

In two marketing departments I worked in, visual design and consumer research both reported to the C-level marketing director, along with a person or team whose role involved looking at data to show how people were using the products. The overall goal was to to grow the brand.

The central question for the marketing director was “what are customers saying about us?” — if it was good things, they were published in the brochures. If it was bad things, we’d request changes to the product.

Teams were arranged by segment, with each PM and PMM managing a portfolio based on sector or demographic needs. (In an education company, this was “primary schools”, “workplace training”, etc.) Marketing and product teams were co-located, and bickered endlessly for the same reasons Yahoo found in 2006 when it reorganised to become more user-centric:

“Seven product units were merged into a group called Audience and another seven moved into a group called Advertisers and Publishers. A unit dubbed Technology would provide infrastructure for the two new operating groups. […] Audience demanded tailored solutions that Technology could not provide at a reasonable cost. Advertisers and Publishers needed its own set of unique products and so was constantly competing with Audience for scarce developer time. In response, Yahoo executives created new roles and management levels to coordinate the units. The organization ballooned to 12 layers, product development slowed as decisions stalled, and overhead costs increased.”

Conway’s Law predicts that bloated, complicated teams ship bloated, complicated products — and yes, that is true — but even though the well-resourced Customer Insights and Design teams could provide seamless UX coverage at every level of seniority, the sluggish decision chain stifled innovation even in a UX Level 5 company.

Product focus

You build the wrong products the right way.

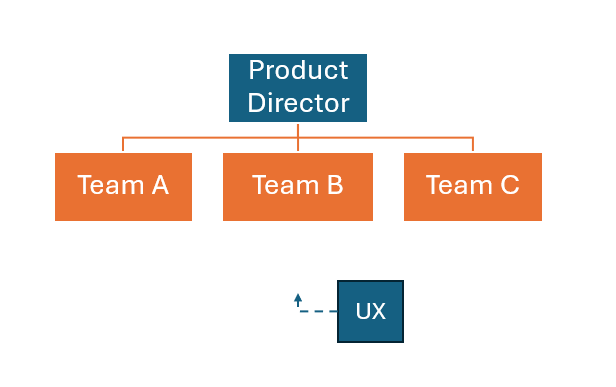

Many startups align people around products, working in cross-functional Scrum or Kanban teams. There may be no professional researchers at all, with the work conducted by marketers and designers until a UX researcher is hired to provide research services across several teams.

Nielsen Norman Group describes this as a Centralized Model, since the UX and product teams are wholly separate and UX is a shared consultancy service.

For the product team, the central question is “how can I grow this product?” which drives demand for research “validating” the market for a product, rather than guiding the teams in deciding what to build.

In an early-stage startup, not only is research typically conducted by people with not much training or experience in doing it — which is exactly like a designer with no software background randomly pushing their own code to production — but there’s no assumption that it ought to be done by someone with extensive training doing it, because lack of good research isn’t a barrier between the product manager and their goal.

It’s not that product managers intentionally want to ship bad products, and most really do want to ship good products, but a BDM cannot make a sale without good understanding of client needs, and the same is not true of product managers: they can still build their product, even with no research at all.

Even once researchers are in place, the over-emphasis of evaluative/usability rather than generative/discovery research means you often know what’s wrong with a product without really understanding why.

As the product director’s focus is on meeting delivery targets, the growth strategy might be unclear. In a strategy- or business development-focussed company, products are commissioned in response to validated needs; in a product-focussed company, products are built that they then try to sell.

In a more mature product-focussed company, the UX teams work in a matrix structure, embedding researchers and designers in each product team to work cross-functionally with the PM, PMM and engineers. It can work well, enabling rapid decision-making and responsiveness — so long as you stand guard against the inherent risks of this structure.

Avoiding the structure trap

- Strategy-focused companies can avoid the structure trap by conducting evaluative research (including usability testing by UX specialists) to check their blind spot: a lack of incentive to improve the after-sales user experience.

- Business development-focused companies can avoid the structure trap by finding ways to improve the experience for all users to avoid a dangerous reliance on a handful of high-value clients.

- Marketing-focused companies can avoid the structure trap by tightening the links between marketing/research/design and technical functions to avoid conflicts and delays.

- Product-focused companies can avoid the structure trap by conducting generative research (including needfinding discovery interviews by UX and market research specialists) to check their blind spot: defining the buyer’s needs first.

How to avoid the structure trap was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply