A reflection on data disclosure in the context of LLMs.

The other day, I asked Perplexity: “Why, when it comes to Web Design, deceptive patterns are a well-recognized topic?”

And the answer was:

When it comes to web design, Deceptive Patterns are a well-recognized topic due to their prevalence and impact on users. […]

Perplexity, on one hand, observes the prevalence, citing a Nielsen Norman Group article that claims a 2019 study found deceptive patterns on over 10% of a sample of 11,000 popular e-commerce sites, likely increasing due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

And on the other side, it highlights their impact, indicating that these practices actually harm both users and, sometimes, companies, and that it’s important to learn how to recognize and avoid them.

In fact, since 2010, many people and professionals have been dedicated to addressing this issue, working daily to make the Internet a more transparent and safe space.

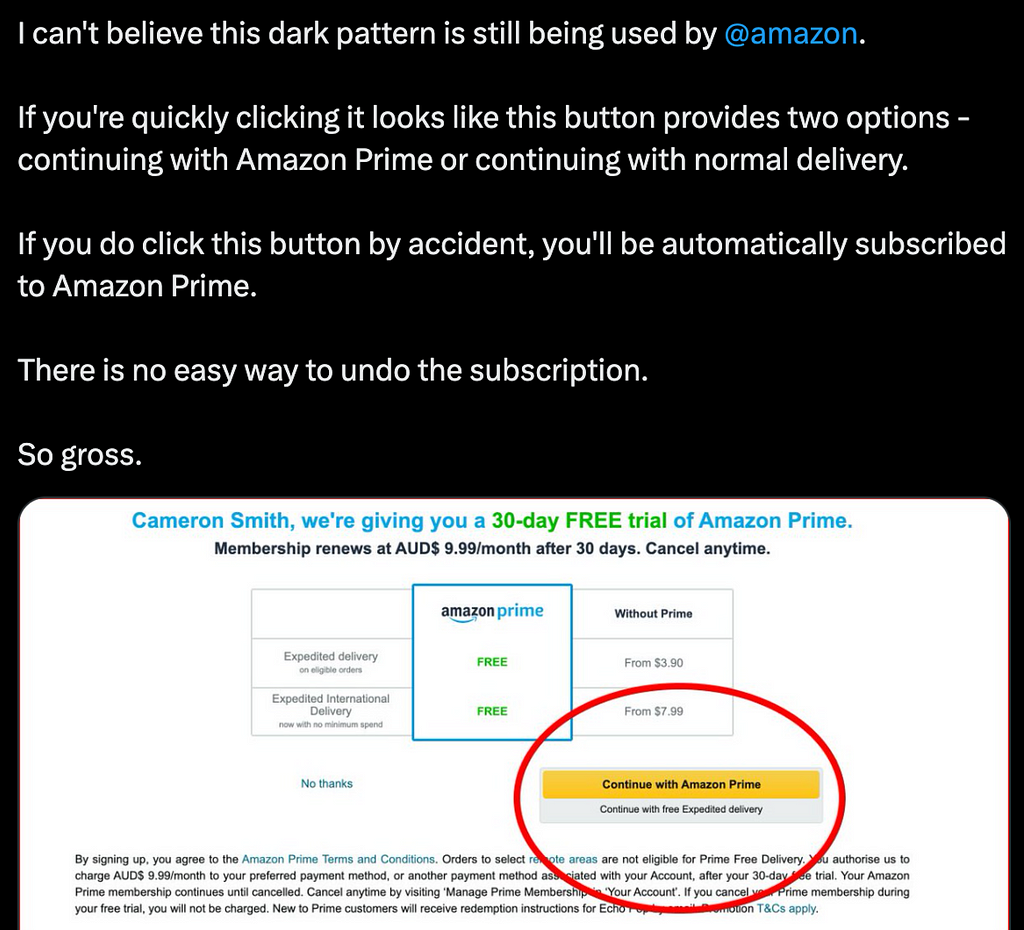

And luckily nowadays, many people can recognize a deceptive pattern when they see one and report it, drawing others’ attention to it.

But what are the returns of these patterns, usually?

Sometimes it’s about getting immediate revenue streams, and others it’s about the opportunity of getting them in the mid term.

But other times, especially in the last decade, it’s accessing the information needed to possibly shape those revenue streams.

In other words, data.

Back in 2021 WhatsApp sent a notification to all its users announcing changes to its Terms and Conditions.

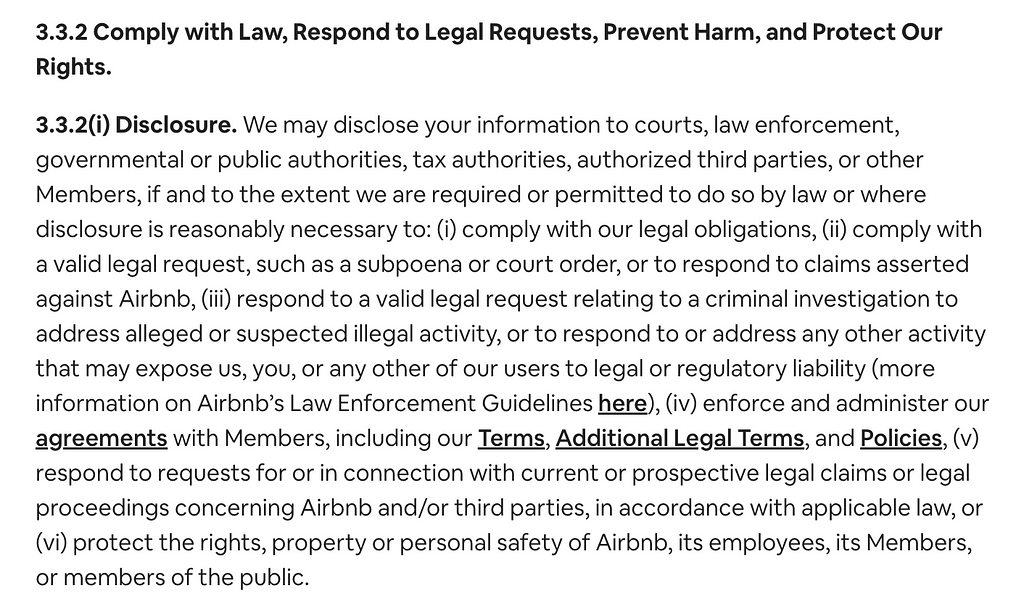

The Privacy Policy states:

“As part of the Facebook family of companies, WhatsApp receives information from, and shares information with, this family of companies”

And also

“We may use the information we receive from them, and they may use the information we share with them, to help operate, provide, improve, understand, customize, support, and market our Services and their offerings.”

Something significant was happening; the most used apps on our smartphones were requesting access to our information with the goal of cooperating and improve their services, and therefore our digital experiences.

Yet, the concept of improvement is always multifaceted.

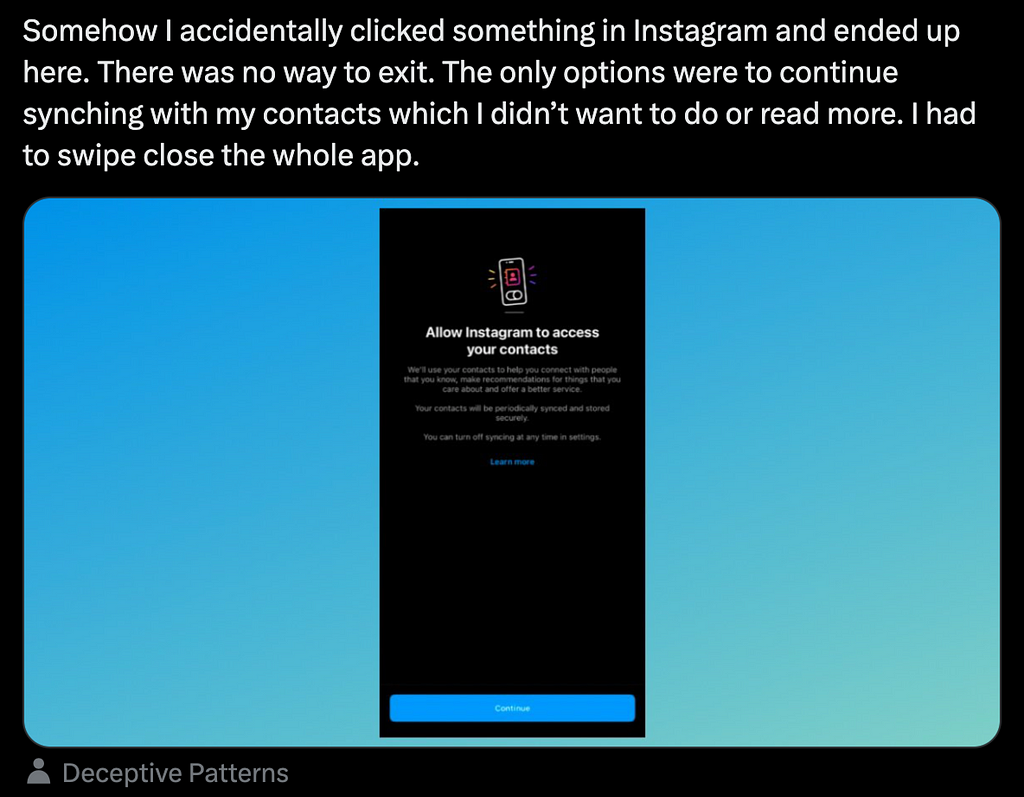

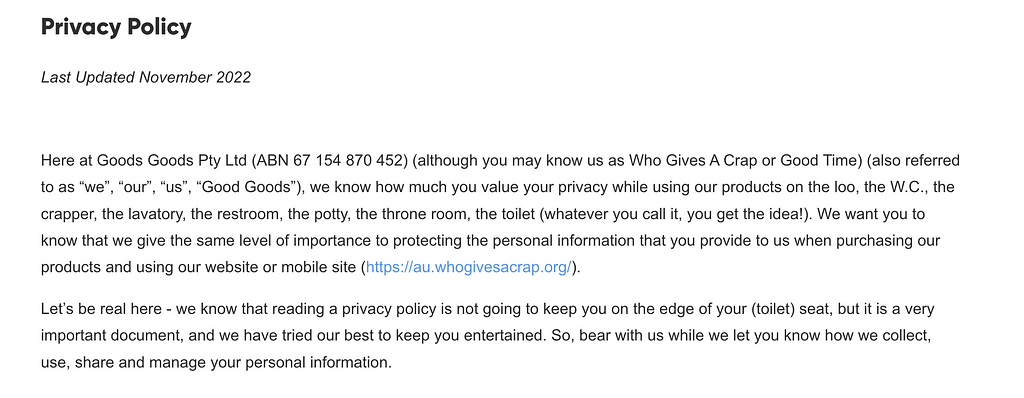

When it comes to privacy policies, people often struggle to understand what they really entail.

In fact, products policies and regulations are often hardly accessible due to their jargon (as remarked in the article “We Read 150 Privacy Policies. They Were an Incomprehensible Disaster” by Kevin Litman-Navarro), and in some cases they are unknowingly accepted, but in others, they lead to reactions of distrust.

Therefore, it’s our responsibility as designers to ensure that those procedures and requests are made in an understandable way, and also possibly collaborate with legal professionals in order to format that content strategically (as remarked in the article “Deceptive patterns in data protection (and what UX designers can do about them)” by Luiza Jarovsky).

In this context is worth asking: what happens when a deceptive pattern is hidden in a privacy policy? In such case, people not only feel cheated but also somehow violated and unsafe.

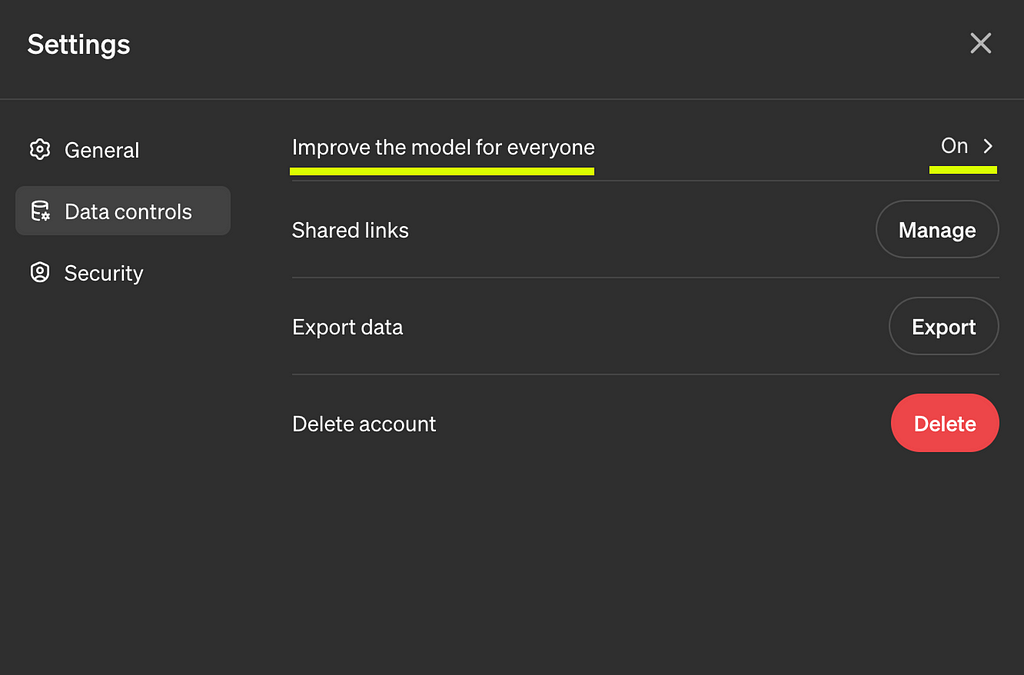

And that’s exactly the feeling I experienced when some time ago I opened the settings of ChatGPT.

When a person creates an OpenAI profile, there’s an option that is automatically activated that says “Improve the model for everyone”.

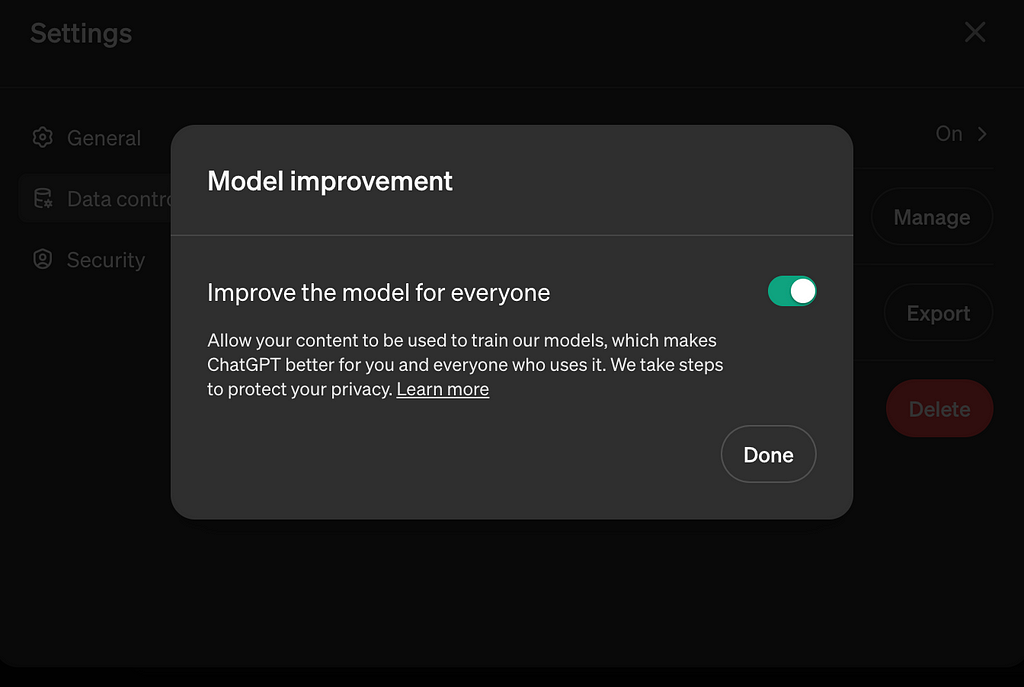

Before delving into the structure of the deceptive pattern itself, I’d like to briefly analyze its language.

Improve the model for everyone

When a person reads these words, they not only feel like they’re doing something positive for the community, but they also feel empowered to commit to a fair action (a feeling confirmed by the word “improve”, on which we once again confirm its ambiguous usage).

But let’s come to the structure.

The core of the issue isn’t necessarily that OpenAI wants to use the content we provide to its systems to improve their models (even though it would be necessary to provide further explanation since not everyone is familiar with LLMs training); the problem is that it doesn’t clearly ask for it as soon as an account is created.

And this specific way of structuring a deceptive pattern reveals another layer of data disclosure.

Let’s briefly go back to the language:

Allow your content to be used to train our models, which makes ChatGPT better for you and for everyone who uses it . We take steps to protect your privacy. Learn more

In a world where tools like ChatGPT are becoming part of our daily routine (both professional and personal), we’re no longer just talking about diagnostic data, we’re talking about content.

We’re talking about moods, behaviors, private reflections, unpublished works and creative habits. We’re talking about sharing our intimate expressions and individual essences.

And we should all agree that it’s everyone’s right to immediately acknowledge if those are being used to improve any AI models.

Without adequate clarity and transparency on this front, we are facing a new frontier of deceptive patterns that risks jeopardizing a new relationship with some of the most powerful and innovative tools of our contemporary age.

The good news, however, is that there are realities that are taking steps to flag this issue and highlighting the need of transparent regulations.

As Illia Polosukhin, Co-Founder of NEAR and CEO of NEAR Foundation, points out in his blog article Self-Sovereignty Is NEAR: A Vision for Our Ecosystem:

[…] People need to own their data so they know what it’s being used for and so they can actively consent to personalized experiences they think will improve their lives. Models must be governed transparently, in public, with clear rules and monitoring to proactively manage risk and reputation systems to build more clarity around information and traceability. Web3 can help to uphold, scale, and manage such systems to ensure AI is a force for good while also preventing it from being too exploitable. […]

Illia introduces this topic in relation to his past experience as an AI researcher and reflects on how such a powerful technology must be governed transparently.

The Web3 ecosystem, in fact, has at its core values the privacy of each individual and the principle that everyone has the right to own their data, so possibly, as we move forward, these values will help reshape our digital interactions.

Also, it’s worth mentioning that in January 2024, the Data Act came into force, with implementation scheduled for September 2025.

This new EU regulation focuses on creating fair rules for accessing and using data, with the possibility that looking ahead, not only clarity can be brought to this topic, but also imbalances that have existed for several years can be addressed.

Deceptive patterns have always had multiple forms, it is therefore essential to monitor their development in relation to those technologies that are increasingly shaping our future.

When inputting our content and information somewhere, we should always remember to pause, ask ourselves questions and claiming for answers.

Encouraging companies, technologies and designers to make digital products safe and transparent is necessary, but critical thinking is crucial, always.

Deceptive patterns in the era of AI writing assistants was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply