Diversity has an inclusion problem

And how design thinking contributes to it.

If you search on Google inclusivity images, you will probably end up with something like this:

…which is perhaps the typical, succinct image most organizations utilize to define diversity in promotional materials and corporate photos. But not enough to call the need to address the complexity of inclusion.

The role of social media has been pivotal, pushing the boundaries of awareness and arming individuals with the knowledge needed to challenge inequality. Minorities experience exclusion daily through products, language, and subtle biases in day-to-day interactions.

But do organizations truly commit to making their diverse groups feel included?

When design fails

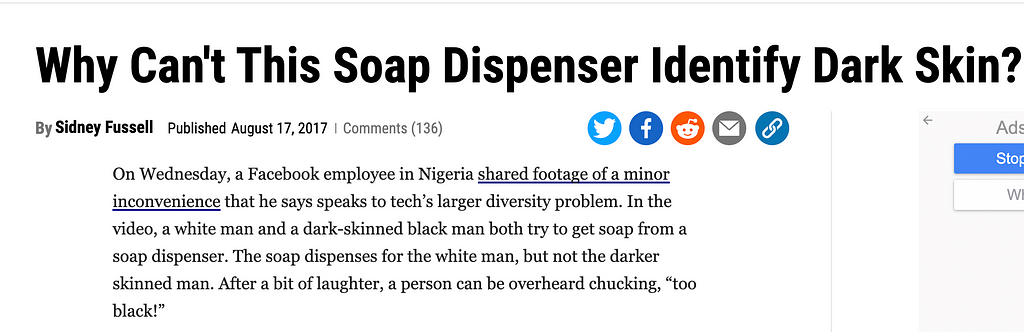

When diversity of thought, background, and experience is not adequately represented in the creation process (through inclusivity), the result is products that cater to a limited segment of society, inadvertently perpetuating exclusion. Designs and products fail when the designer is not empowered to ask why. In the desperate need of becoming the design disruptors and the ones that come up with the next big thing, we forgot to focus on intent and service.

Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to recognize and actively counteract our biases. It involves creating spaces where diverse perspectives are not only heard but are integral to the decision-making process. This means going beyond “tokenistic” gestures of inclusion to foster an environment where diversity is genuinely valued and leveraged for its potential to drive innovation and creativity.

The problem is so embedded in our day-to-day behaviors that we might not realize it’s an issue unless we are part of that culture or group and experience it ourselves.

We all have blind spots. Which ones are yours?

Language has undergone significant transformations over the centuries, adapting and morphing in response to cultural shifts and societal changes. Among these are terms such as “master bedroom,” which carries connotations of dominance and hierarchy; phrases like “black sheep” and “blacklist,” which unconsciously perpetuate negative associations with the color black; and the use of “nude color” to describe a skin tone that is typically light and excludes a vast range of other skin tones.

This oversight is not merely a matter of semantics but a reflection of broader societal blind spots and a lack of awareness. Despite the rich tapestry of human diversity — encompassing emotional, social, cultural, and spiritual dimensions — we often resort to oversimplification and generalization through our lenses. Personas are one example of how organizations try to account for multiple scenarios when addressing needs. Still, they often represent lots of subconscious biases through the demographics and segmented data findings. When stored inside corporate silos, data becomes nugatory. User research allows corporations to minimize existing unconscious bias. A few categories of biases include:

- Confirmation bias

- Affinity bias

- Attribution bias

- Conformity bias

- The halo effect

- The horns effect

- Contrast effect

- Gender bias

- Ageism

- Name bias

- Beauty bias

- Height bias

- Anchor bias

- Nonverbal bias

- Authority bias

- Overconfidence bias

Or they are known as short our blind spots.

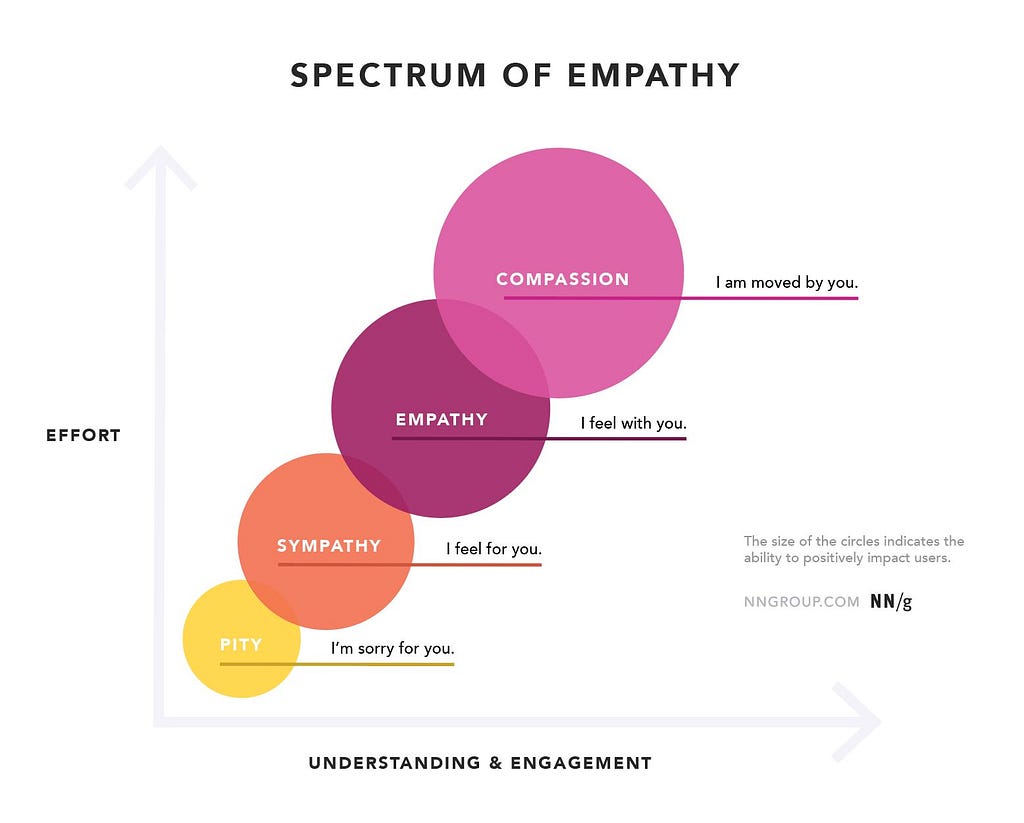

Empathy is the first step in design thinking

Yet it emerges as the most overlooked blind spot within corporate landscapes

The notion of empathy is widely used across multiple domains but is especially emphasized in product development. Empathy is a term that we speak of so much in our industry without adequately integrating its meaning into the design process. True integration of empathy into product development requires more than just understanding users’ needs from a surface level. It involves a deep, genuine effort to understand the emotions, experiences, and contexts that shape user interactions with products. This means going beyond traditional market research or user testing to engage with the lived experiences of the target audience, especially those from underrepresented or marginalized groups.

Empathy is difficult to achieve

Corporations often tout Design Thinking as the cornerstone of their design and product development strategies, emphasizing its user-centered approach as key to innovation. However, the reality reflected in many products suggests a disconnect between this ideal and its execution.

Although introduced across organizations, the practice of design thinking is challenged as it is based on user empathy. And that’s what makes this entire process absurd, as Lee Vinsel wrote back in this article in 2018.

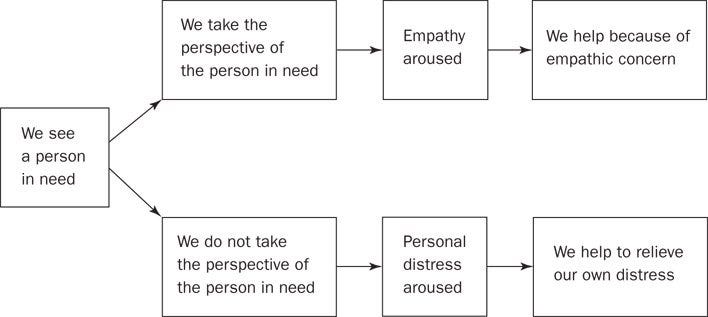

Psychology theories like Batson’s empathy-altruism hypothesis state that feeling empathy toward a person is enough for someone to be altruistic without seeking gain in a situation. Another interpretation based on the empathy-altruism concept is the insight that the self-concept is located outside the individual and inside other close individuals. Cialdini, Brown, Lewis, Luce, and Neuberg (1997) introduced the concept of oneness to describe self-other relationship overlapping, and feelings of empathetic concern are predicated on feelings of oneness (Levine et al.).

Real progress demands a cultural shift within organizations, recognizing that the era of designing primarily for the majority is behind us. It calls for a proactive approach that values the existence and experiences of all humans, rather than being merely reactive to legal pressures or lawsuits.

Feedback is the research killer

Designers often look for “feedback” as part of their progress. But feedback is the research killer. The designer is supposed to iterate and test the hypothesis (the design) with a diverse set of users. Yet, the quest for feedback often morphs into a quest for confirmation, subtly shifting the focus from genuine exploration to validation of pre-existing ideas. This tendency towards confirmation bias is precisely why the role of moderators in testing sessions is critical. Without it, unchecked biases are a significant factor in diminishing product quality, as they prevent the design from truly resonating with the broad spectrum of user needs and experiences.

So who are we designing for?

Organizational structures and leadership teams, often characterized by their predominantly white and male composition, are a fundamental reason for the challenges in achieving true diversity and inclusivity in design and product development.

It’s difficult to look beyond the corporate veil of words, and truly see that inclusivity exists when organizations fail to acknowledge or celebrate the diversity they try to bring, whether is by celebrating all non-Christian holidays (like Muslim holidays for instance), ensuring equity in compensation, and even creating safe environments where people dare to say “I am not ok”. The gap between aspiration and reality is beyond the role of the designer. While the designer can impact the product and help shift the mentality (slowly), the responsibility for fostering inclusivity also heavily rests on the leadership team. Lastly, inclusivity is a continuous commitment, and not only confined to days, weeks, or dedicated months throughout the year.

We’ve made SOME progress. Like this company, Immortal Cosmetic Art in Nigeria, which creates prostheses for people of color, or companies like Tru-Color bandages which is black-owned and they take inclusivity seriously.

Or have you ever thought about how a deaf person might be able to experience a concert? While I bring up accessibility, here is another example of how two blind brothers brought awareness through their product on how blind people shop. And as Gen-Z consumers are creating a demand for more inclusive and gender neutral clothing, retailers like Pacsun are taking a stab at it. And probably there are more — feel free to share.

In conclusion? When it comes to product design and life experiences, let’s focus less on the importance of design thinking and more on inclusivity and the depth that comes with it. Everything else in the design process will follow naturally when the intent and the right questions are asked.

Some additional reads on the topic:

- The decline in Design (Thinking)

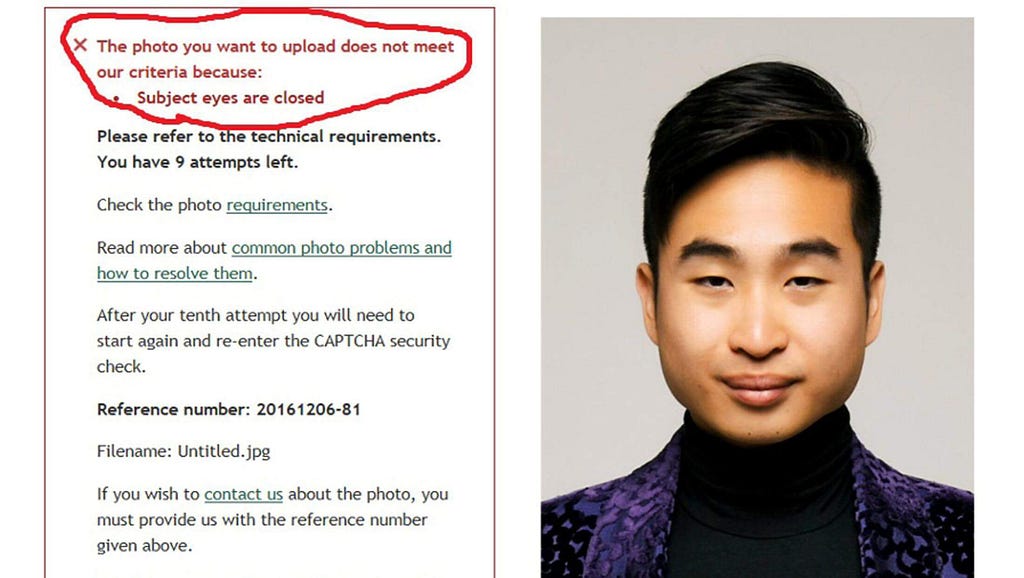

- An algorithm rejected an Asian man's passport photo for having "closed eyes"

- 16 Unconscious Bias Examples and How to Avoid Them in the Workplace

- Prosocial – Cognitive & SOCI

- Evidence that a simpático self-schema accounts for differences in the self-concepts and social behavior of Latinos versus Whites (and Blacks) – PubMed

If you liked this, here is how you can support:

👏 Clap, share & follow

👩💻 Connect with me on LinkedIn

The state of inclusivity in 2024 was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply