The sociology of the big difference between Western minds and those of the Far East

I can’t believe I am writing this, but… as UX designers, we must understand the users. Shocker!

However, is this enough when we design international products?

Perhaps not. I believe only interviewing users doesn’t give you a full understanding. You get an idea of the user’s behaviour but not the causes of these very behaviours.

Multicultural UX design is complex.

To get a profound comprehension of our target culture, we need to understand its history.

Which country can be better used than Japan to illustrate this case?

Japan has a rich history. It’s an intriguing country. It perfectly explains why historical comprehension is tremendously important for us UX designers.

In this article, I will discover Japan’s past and how historical events influence today’s digital behaviour.

Let’s start at the beginning

Allow me to write this from a Western perspective.

To understand Japan, we must go further than Japan's own history. We should understand the general difference between Western culture and the Far East.

We need to look at the Greek and Chinese.

The real “old Greeks”, the ones before Athens, were located on mountainous lands. These people lived in valleys and thus in relative isolation from each other. The only thing that mattered to them was what happened in their own valley. These people could be self-sufficient without having to rely much on cooperation. Those Greeks were, in essence, hunters and gatherers.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the planet, Chinese people had a different environment.

The Asian tribes lived around the Huáng hé. Everyone relied on this (yellow) river for a healthy agricultural outcome (rice farming). Coordination and central control were thus needed. Ensuring harmony was the goal.

When agriculture arrived in Greece, wine and olive oil production became the objective, turning the independent tribes into businessmen. Competition became the norm.

Philosophers

These different lifestyles greatly impacted how the most influential philosophers of that time thought about the world.

The Greek philosophers, mainly Plato and Aristotle, approached thinking from independent objects: a house, a person, or anything materialistic. Similar to how the peasants only had to think about their own valley.

These farmers’ behaviours also promoted debate. They were not relying on their neighbours and could afford to disagree with others. Greek philosophy is about debate and individual freedom.

The Chinese thought leader, Confucius, didn’t dedicate much of his work to objects. He mostly considered the relations among people. A harmonious social network was desired in his view, and a hierarchical social system was needed to maintain balance and peace.

For the Greeks, the truth was the goal; for the Chinese, the way was more important.

Now, the obligatory multicultural disclaimer: Greece is neither the US nor the UK, and China is neither Japan nor Korea. But we must start at the beginning of our civilisation to understand contemporary behaviour.

Japan has many unique characteristics, which we will discuss later. In this stage of the article, we just need to realise that numerous Japanese traits have originated on Asia’s mainland.

Confucianism has massively influenced Japan since the 6th century. This included concepts of Ethics, Governance, Education, and Filial Piety (family values and respect).

Holistic thinking

One of the most significant differences between Western and Eastern societies is how people view things.

We already discussed that Greek philosophers focus much more on individual objects than Eastern thinkers, who look more holistically.

This tendency hasn’t changed throughout history.

An article in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin studied Western and Eastern traditional art.

The researchers looked at how East Asians and Westerners draw landscape pictures and take portrait photographs. When looking at all the old artwork, a clear pattern emerges.

Ancient East Asian artists drew the horizon higher than their Western peers.

This allows the painter to include more contextual information and objects, like mountains, rivers, or people.

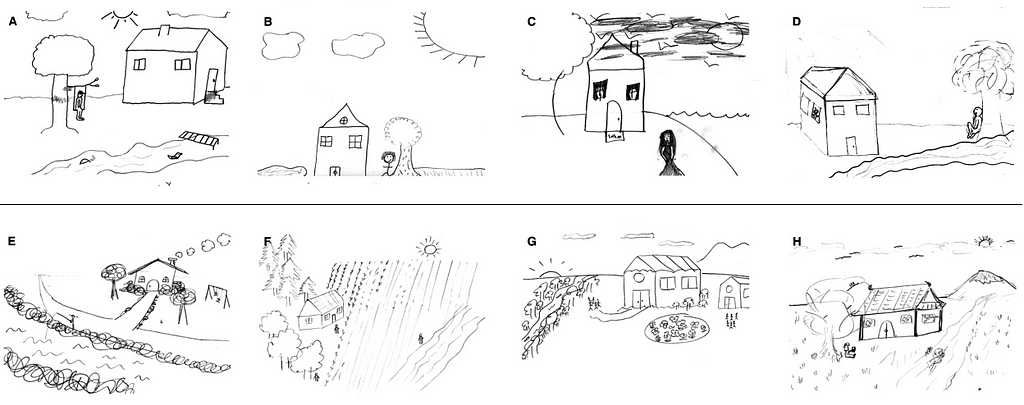

The researchers also asked contemporary members of East Asian and Western cultures to draw images.

The results were consistent with those of ancient painters. The scientists counted the number of contextual objects that were drawn. Asian drawings (number E-H in the screenshot above) contained more context than Western images (A-D). This proved that East Asians look more holistically.

The same article also studied whether portrait paintings and photography would have a similar trend.

The size of the person who was photographed was smaller in East Asian portraits than in Western portraits or paintings. The Asian portraits, therefore, contained much more environmental information.

The article concluded East Asians use “contextual information at the expense of the figure in the scene.”

The subjects that used a photo camera also showed a clear difference:

The results of the photograph-taking task indicated that East Asians were more likely than Westerners to set the zoom function to make the model small and the context large.

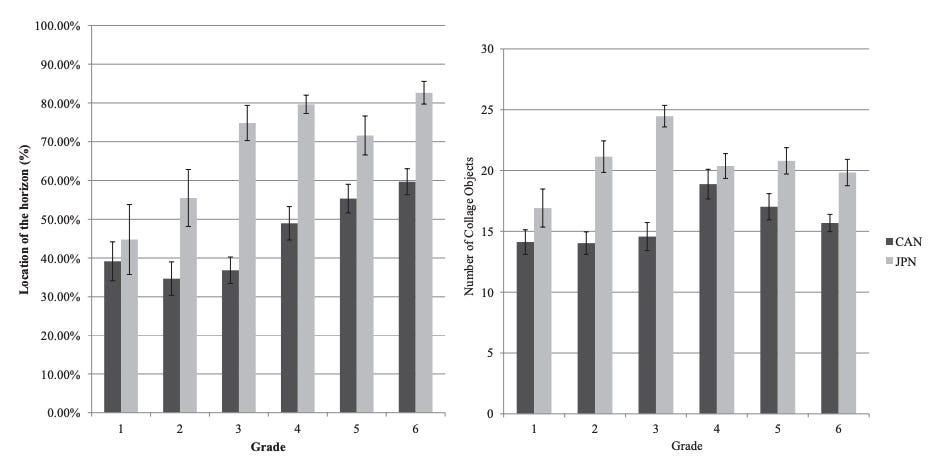

Another study in the Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology compared drawings from Canadian and Japanese children.

They found that the Japanese placed the location of the horizon significantly higher than the Canadian kids in all grades of primary school. The number of objects in Japanese drawings was also much higher.

The scientists drew similar conclusions from the results.

The higher placement of the horizon is linked to the context-oriented visual attention style seen in adults’ drawings and historical paintings in East Asian cultures, as opposed to object-focused drawing styles commonly seen in North American cultures.

What about graphical and UX design?

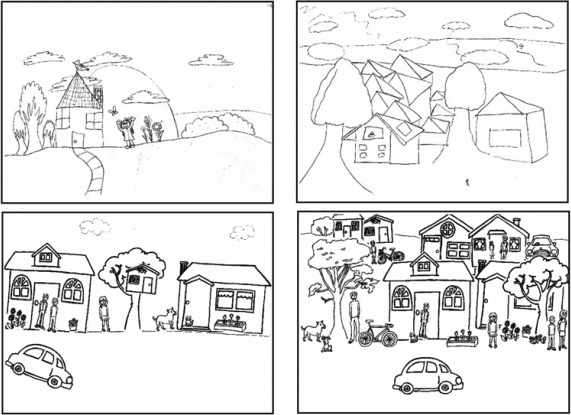

Researchers at the University of Alberta in Edmonton compared East Asian and Canadian designs. They looked at both print posters and governmental and university websites.

In both cases, the Asian designs were much more information-rich and dense.

The researchers also investigated how quickly the participants were able to process information.

They examined how fast participants were able to find something on the websites. They asked them to identify target objects on mock web pages containing large amounts of information.

The results indicated that East Asian international students are faster than European Canadian participants in dealing with information on information-rich webpages, but such an advantage was not observed with short webpages.

They concluded:

“We identified systematic cultural differences in the amount of information in cultural products and in people’s skill in handling large amounts of information”

This difference can be seen when comparing Japanese and Western websites of the same company.

The Japanese Rakuten website is full of text and clues, whereas the British version of Rakuten’s homepage is very minimal.

The Japanese alphabet

The holistic mind gives Japanese people a desire for more complex UIs. Wouldn't it be easy if this was the single thing that explains their UX design trends?

Of course, but cultures aren’t that linear. They are rather complex.

Next to a holistic mind, the Japanese use a different alphabet. This can also influence behaviour.

The Japanese writing system is a combination of several scripts. Kanji, the main script, was borrowed from the Chinese. Kanji literally means “characters of Han (China).”

The Chinese alphabet didn’t cover all of the Japanese cases. Japan had their own terms and names. Therefore, Hiragana and Katakana were added later.

Hiragana is a phonetic lettering system. Each sound (or syllable) is written with one or two characters called mora. The term hiragana is derived from the word “simple” or “flowing”.

Katakana is usually used for words that find their origin in other languages. Names of people, cities, plants, animals, foreign jargon, etc.

The (Arabic) numbers (1, 2, 3 etc.) are also used in Japanese. Japanese also have their own year numbering system based on each emperor's reign. This also comes back in their UXs.

No bold or italic

Unlike languages that use the Latin alphabet, Japanese fonts don’t have italic or capital letters. This makes it harder to highlight certain words visually. Japanese designers often use decoration or graphic elements to compensate for this limitation.

Japanese sentences can also be displayed horizontally or vertically, which might appear unorganised to Westerners.

Reading speed

Languages like Japanese use characters that can hold a lot of meaning in one character: a so-called logogram. This type of writing may appear crowded to Westerners, but it allows the Japanese to process information quickly.

Something else that helps with quick reading is that Japanese people don’t have a need to pronounce the words in their heads. Western readers use a concept called subvocalising. We learn in primary school to read out loud the words we process.

At a later age, we will still do this in our heads.

In Japanese, you can recognise characters' meanings without pronouncing them. This allows for much quicker reading.

Complexity of fonts

Creating a Latin font requires you to design a variety of glyphs for each character: A, a, a and 1, 1. This means around 200 unique glyphs are needed. If you want to include the other languages based on the Latin alphabet, like all the odd German, Scandinavian, and Romanian accents, a total of less than 1000 glyphs is enough.

The JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards) specifies a set of 2,136 kanji characters known as the Jōyō Kanji. These are considered essential for daily use in newspapers, official documents, and education.

Hiragana and Kataka both contain 46 basic characters.

Akira Kobayashi, a renowned Japanese font designer, explains in an interview with Smashing Magazine that:

“A set of proper Japanese fonts requires approximately 7,000 characters and takes a couple of years to complete by an entire team of skilled designers.”

As a result, there are much fewer Japanese fonts on the market. This naturally leads to more uniformity in the lay-outs. Designers are forced to use the same fonts.

Typing in Japanese

Having this many characters makes typing in Japanese more difficult, both on a mobile phone and on a desktop.

This means that Japanese people are less inclined to use the search bar. As a result, websites show a more link-based browsing mechanism, cluttering the UI further.

We now know that Japanese like to look more holistically and that their alphabet is more information-rich and easily digestible. They also need a more elaborate navigation structure to avoid using the search bar.

These are 3 reasons why Japanese designs look more cluttered.

The need for information

It’s no wonder that Tsunami is a Japanese word. The country is, due to its geographical location, always been under threat of earthquakes, volcano eruptions, tidal waves, and typhoons.

The Japanese have emergency plans for these natural disasters.

The country is prepared for the worst and has protocols in place to deal with the unknown.

Japan also lives according to the spirit of Do.

Do comes from the Chinese word of Tao. Taoism has been influencing Zen Buddhism and reached Japan more than a thousand years ago.

Do literally means “way” and describes the way something should be practised.

Think about the “do” in budo forms (the way of martial) like judo, kendo, and aikido. Sado (the way of Tea), Kado (the way of flowers), and Shodo (the way of the brush — calligraphy) are other examples that illustrate do.

In these fields, “Do” requires a holistic approach to personal development, not just technical proficiency.

Philosophical beliefs and natural threats made Japan a country that heavily relies on rituals, protocols, and everything that can be used to increase predictability.

Before any project can start in corporate Japan, much effort is put into feasibility studies. All the risk factors are considered beforehand.

Those who’ve read my older cultural articles know where this is going: Japan scores really high on uncertainty avoidance.

Countries high on uncertainty avoidance have less tolerance for ambiguity.

This can be easily noticed at Japanese restaurants. Models of food plates are shown so that customers know exactly what they’ll order.

The most effective way to deal with uncertainty in UX design is by providing complete and elaborate information.

Japanese users tend to feel more reassured when there is more information available. For Japanese people, the more detailed the information, the more trustworthy it seems. Therefore, Japanese design primarily focuses on “conveying information” as its main objective, with “presentation/look” being secondary.

– Source

This can also be observed in the design of Social Media thumbnails. For Westerners, Japanese thumbnails look messy and cluttered. For the Japanese, the images show what they can expect after a click.

It works because we also learned that it takes them less cognitive capacity to digest all the information that is displayed.

Who makes the decisions?

To understand Japanese culture more deeply, we must return to the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. During these medieval times, the Japanese developed the ie system. Ie translates to “house” or “family”.

The system works with so-called patrilineal descent: men are responsible for inheritance, succession, and carrying on the family name. Not the women.

Families used to live together in a single house, with members from different generations. The head was usually the father or the oldest son. It was up to them to make all the decisions for everyone.

Japanese society had distinct gender roles, derived from Confucianism: men outside, women inside. Men were responsible for labour outside the home, while women were responsible for domestic duties and child-rearing.

This patriarchal culture has been gradually changing, mostly after the 2nd world War.

Nevertheless, Japan still ranks highest on the cultural dimension of decisiveness vs consensus. This dimension was formally known as masculinity vs femininity and contains aspects like whether the role of genders should differ or overlap and if status is important.

In Japan, the male can still be seen as the head of the family and thus makes the decisions.

In UX, male and female users may be motivated differently, with males often being more logic-driven and females more emotion-driven.

This means that product pages on websites need to show a lot of specifications:

Whether a Japanese male is a traditional type who makes decisions on behalf of the whole family or the modern type who needs to convince a partner first, technological talking points help his case. He doesn’t need to truly understand the tech, he just needs to think that he understands it, and Japanese sites try their best to provide that environment.

– Source

Japanese people rely heavily on product specifications.

Reading between the lines

Japanese culture is a great example of a phenomenon called geographic determinism. The landscape and location of a country have a big impact on its culture.

The book The Japanese Mind explains this perfectly.

Because of the dangerous and unpredictable seas separating Japan from the Asian continent, Japanese culture was able to develop in relative isolation, free from the threat of invasion from other countries.

Japan is also a mountainous country and does not have a great deal of inhabitable land; as a result, people had to live close together in communities in which everyone was well acquainted with one another.

The more isolated a country is, the more people have the ability to refine their communication.

The Netherlands and The US are examples of countries with the exact opposite effect. Because these countries always had a multicultural population, subtility in communication was undesirable. When many people come from various cultures, you can’t rely on deep cultural communication conventions. People wouldn’t be able to understand each other.

Therefore, Americans have a low-context culture. What is said is what is meant. The Dutch are known for their directness. There is no context at all.

Because the Japanese mostly communicated only with themselves, they became amongst the highest context cultures in the world.

They have the concept of wa. Harmony is essential in maintaining relationships.

Another quote from The Japanese Mind.

People avoided expressing their ideas clearly, even to the point of avoiding giving a simple yes or no answer. If a person really wanted to say no, he or she said nothing at first, then used vague expressions that conveyed the nuance of disagreement.

In the beginning of this article, we established that Japanese websites contain a lot of text. This works perfectly if you need elaborate navigation structures and detailed specifications. Or when you prefer holistic information: all information on a single page.

Words are sometimes less useful for high-context cultures, especially when you convey something with emotion, criticism, or encouragement.

East Asian cultures often use photography to convey messages. This helps to let the user find the meaning behind the primary communication, instead of having it spelled out.

Emojis are another way for Japanese people to use subtleties in their communication.

No wonder the term “emoji” is a Japanese word. “E” means picture, and “moji” means character.

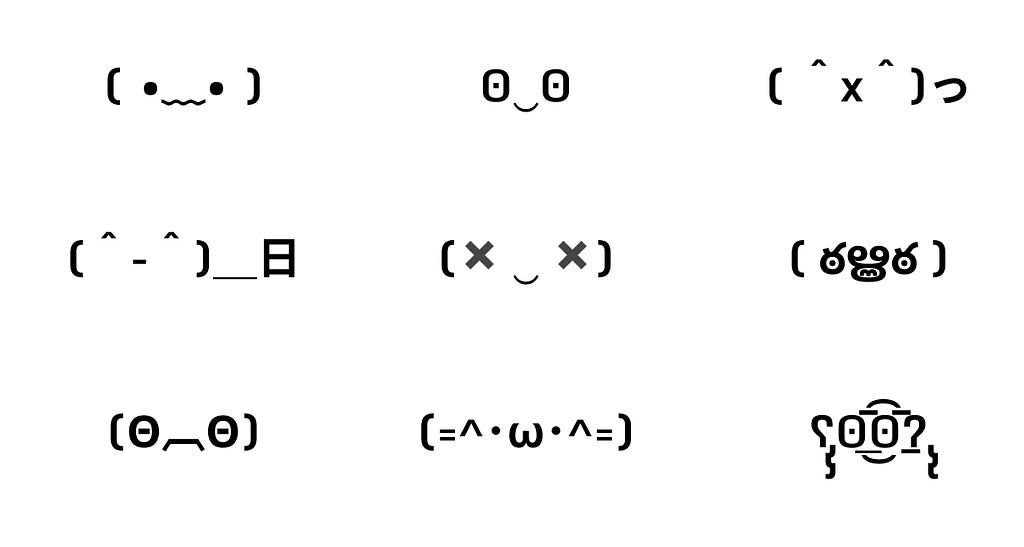

Before emoji, in the ’90s, the Japanese used kaomoji instead of the Western emoticons, the smileys like :-).

“Kao” means face, so kaomoji means face characters.

Kaomoji had many more variations than emoji, allowing for much more subtle communication.

The Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh looked into the usage of emoji in their study of The Cultural Differences in the Use of Instant Messaging in Asia and North America.

They concluded that:

A greater percentage of Asians (100%) than North Americans (72%) reported using emoticons on a regular basis. These findings are partially consistent with the hypothesis that emoticons will be more important in Eastern, high-context cultures.

Not only did Asians use emoji more, they also considered them more important:

As expected, there were cultural differences in rated importance. Post-hoc tests indicated that North Americans rated emoticons significantly lower in importance than did Indians, and marginally lower in importance than East Asians.

For high-context cultures, photos and pictograms are a powerful way to convey a message that shouldn’t be spelt out.

In real life, exaggerating facial expressions can be used to indicate your reaction clearly.

Polite speech

Thus far, we have covered that the Japanese like to rely on their etiquette. Polite speech, or Keigo, is another part of their sophisticated social culture. Keigo finds its origins in many historical Japanese influences, like Confucianism and Buddhism, but also in Samurai.

The Japanese use various forms of polite speech. Which one to use? It depends on the context.

Sonkeigo is used to show respect to those higher in status: customers, clients, superiors, and others deserving of honour.

You’d use Kenjougo to humble yourself. For instance, when talking about one’s own actions or possessions.

Teineigo is the standard polite language used in business settings, schools, and formal communication.

One thing UX designers can learn from Japanese politeness is the concept of nemawashi. The word means something like “preparing the roots.”

It basically means that you should build consensus before making a formal proposal.

Many Western UX designers love their ta-daaah moments. They attend stakeholder meetings and present their flashy Figma prototypes as an Apple product launch. However, this will never work in Japan. It actually also doesn’t work in the West.

As a UX designer, you should see yourself more like a diplomat, or a Japanese business person. If you want a design approved, it’s better to “prepare the roots.”

You must first dismantle the potential bombs that could go off in the meetings. You need to create consensus upfront. People want to feel important, especially stakeholders. You should make them feel this way.

Give them a personal treatment, discuss your sketches individually and tailor your design before presenting this to a bigger audience.

This will increase the chances for approval significantly.

The Japanese use nemawashi. It aims to avoid confrontations and ensures harmony.

The missing aspects of this article

This article is getting fairly long, but I haven’t even covered half of the aspects I should write about.

For instance, I didn’t discuss Japanese art (wabi-sabi). This form of aesthetic beauty is characterised by a minimal design. This is inconsistent with how their UIs look, but the desire for accurate information is stronger than for a pleasant aesthetic.

And how does this relate to Manga and Japanese comic culture?

I will cover this more deeply in another article, in which I will also explore colour preferences.

What about the famous electric toilets and the Japanese technological innovations they had?

Conclusion

There has been a fair few people who gave their take on the uniqueness of Japanese UX. There are a number of brilliant articles that I borrowed from and linked to. Check them out!

Some claim that technical limitations and corporate structures are at the foundation of the difference between Western and Japanese tech.

I don’t think so. I hope this article illustrated well enough that the reasons are much more profound and that what happened in the last 30 years is just the result of centuries of social evolution.

Japanese history is so unique and rich that many elements impact contemporary behaviour. It’s distinct and a great example of why international UX designers should study social history.

Explaining contemporary behaviours can only be done by analysing the past.

Each culture has elements we should learn from. I think Japanese culture has many.

Let’s all look a bit more holistically.

Arigatô

ありがとう

The deeper meaning behind Japan’s unique UX design culture was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply