Human-created AI not only has the capability to replace designers, but the potential to make design, as we know it, obsolete.

The truth about research insights.

As a researcher, analyst, data scientist, or other knowledge worker, one of the worst questions you can get about your work is “What is the insight here?”

It’s like if you were a figure skater, and after performing your whole routine in front of a panel of 9 judges, you turn and their scorecards spell out “Is that it?”

That’s the sentiment of an audience that doesn’t feel like they have any new wisdom about the topic after hearing your research. They walk away wondering “Why did I listen to that?”

They think it was a waste of time, and you feel like you failed at your job.

The worst part? There’s some truth to it.

Your hard work wasn’t appreciated or valued by your stakeholders, meaning you look a little worse and your work probably isn’t going to have the impact you wanted it to have.

So what’s the fix? How do you make sure you have insights?

To start, you have to understand what people mean when they ask for insights. And that’s problematic because…

Everybody thinks insights are something different

One of the biggest issues with getting comments like “I didn’t get the insight” is that the word “insight” doesn’t have a standard meaning in an organizational context, which I’ve written about in more detail here.

Asking people what they mean by “insight” is not always effective because a lot of times, people can’t articulate what they are looking for.

It’s as if you cooked a meal for someone and they said “It’s not bad, but it’s missing something,” or “I wasn’t inspired…”

Asking for the missing ingredient might lead you in the wrong direction; they might not be a foodie, and even if they were, a food connoisseur is not the same as a chef (which is you, in this scenario).

In any case, here are some of the main reasons people ask for insights:

- The takeaway is unclear: What was the most important new piece of information or perspective?

- Don’t understand why: What caused the pattern? What does it mean?

- Lost about what to do: What are they supposed to do with this new knowledge?

Clearly, people expect a lot of things out of a single insight, which makes it hard to pin down exactly what an insight is.

Most attempts at defining insights fail

Brief, catchy definitions of insights tend to fail because they oversimplify the concept.

The term “insight” is used so broadly that any quick summary will miss a few things, often focusing on a specific component of what an insight about the customer should have, like the user need or motivation, or the implication to the organization.

The other end of the spectrum doesn’t fare well either; people who try to cover all the bases tend to come up with a bulleted list of criteria for what counts as an insight.

“Insights must be powerful. They must have data, and the human element. They must be surprising, yet make the audience say ‘Of course!’ And they must be actionable.”

This “checklist-style” definition of insights tends to be more helpful as a reference after you’ve already come up with your insights, to see if you’ve met the criteria.

It doesn’t help you create one.

Another problem with existing definitions is that most of them get one important thing wrong.

Insights are not tangible objects

Many attempts at defining insights sound like they are describing a sentence syntax, as if anyone can use a mad-lib to write an insight.

I hate to do this.

I really, honestly do.

Find any dictionary and look up the word “insight.”

That request was rhetorical. To save you some time, I pulled a few definitions for you:

- Collins: “An accurate and deep understanding of a complex situation or problem”

- Merriam-Webster: “The act or result of apprehending the inner nature of things or of seeing intuitively”

- Cambridge: “A clear, deep, and sometimes sudden understanding of a complicated problem or situation”

Notice anything?

Insights are not something you create in a powerpoint or put on a poster and can be stared at by random people passing by.

Insights are subjective experiences inside other people.

The characteristics of an insight

Remember when Archimedes was about to take a bath, realized the water he displaced had the same volume as his ancient Greek ass, and shouted “Eureka!”?

That was an insight.

Insights are not a collection of words.

They can be DOCUMENTED as words, but those words put in front of a random other person might not cause them to have an insight.

Imagine sharing Archimedes’ discovery with your grandmother. Or your coworker. Or a 5-year-old. Or a random teenager who lived 2000+ years ago at the same time as Archimedes. Or to Archimedes himself a week after his famous bath.

You’ll get a range of responses, from “That’s nice, dear” to “huh?” to “WOOOW” to “sure, I know that already.” And not necessarily in that order.

Insights can be CAUSED by words.

Or images.

Or stories.

Or by taking a bath.

The medium of delivery doesn’t matter.

How to create insights

Nothing is insightful to everyone.

Making an audience experience an insight requires you to understand who they are: what they already know, how they think, and what they want.

When someone says “I don’t see an insight…”

It does NOT mean: “Your work is incorrect”

What it ACTUALLY means is “I didn’t experience any perspective shift”

It would be great if you could get in the minds of everyone, figure out the one thing that would be insightful for everyone, isolate the specific phrase that will flip the switch in their minds, and just have that code word in your back pocket.

I’m willing to bet you’re not a Soviet secret agent trainer who can program people to suddenly be inspired to action after you say “butterscotch.”

If you want to give people insights, you’re going to need to do it the hard way.

That means you need to understand how you fit into your organization as a knowledge worker and the necessary transformations needed to go from data to action.

What organizational needs require insights? Who is involved and what do they know and think they know? What do people already want to do and why? How does knowledge transform into action at your organization?

I can’t describe all of that in one sentence.

But I can draw you a picture

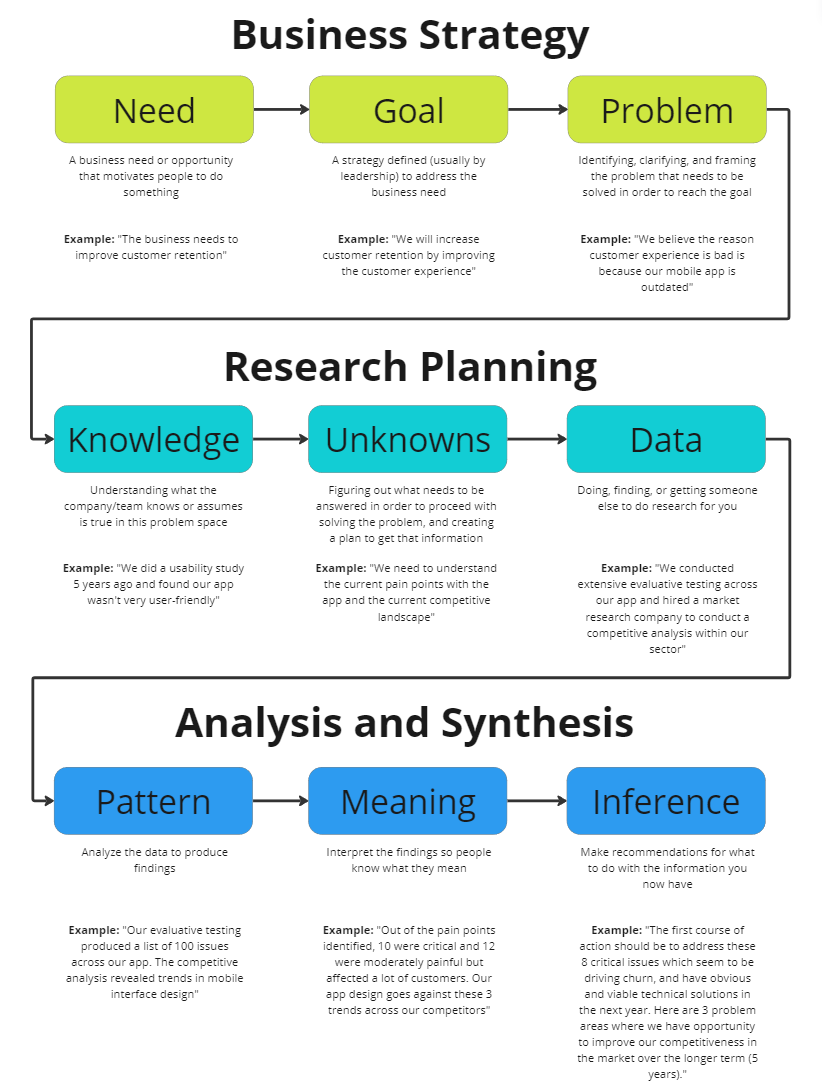

First, let’s map out the process of making an insight-informed decision in a corporate environment, in an ideal scenario. For the sake of simplicity, we’re going to boil it down to 3 phases:

Please do not take this as a blueprint or a how-to guide. It’s not meant to be followed step by step, it’s an oversimplified illustration of the general order in which things can, should, and do happen.

Obviously, steps can be skipped, replaced, or done repeatedly in real life, but we’re going to ignore all of that for the sake of this narrative.

Step 1: Business strategy. Something’s going wrong, or not doing as well as it could with the organization. It usually ties back to earnings, but you need to get a bit more detailed than that. What is the specific business issue that is tied to revenue? Identifying the underlying problem that needs to be solved to make a change in the desired direction is the crux of this part of the process.

Step 2: Research planning. Here we’re going to assume that the corporation values making decisions based on reality, or at least pretends to do so. The next course of action is figuring out what people already know, don’t know, and want to know, and then figuring out a way to bridge the parts of the gap that are needed to move forward. Some form of research and data collection is usually the way to do that, but this process cannot possibly succeed with only researchers in the room. You must involve the actual people you intend to give insights to and inspire to action.

Step 3: Analysis and synthesis. Stereotypically this is where the scientists and data nerds go into a cave and do their thing to make the data useful and pump out the insights. This usually means taking the raw data and pulling out the interesting bits, making those bits make sense, and then making an inference about what should be done about it. Outside of an academic setting, this is way more effective if researchers include their partners in design, product, and tech as well. After all, how else would a researcher know what technical solutions are viable within the next year?

Where’s the insight?

You’re right to be impatient, I’ve gone against my usual recommendations and talked a lot at you without giving you a direct answer. If you’re still with me, here it is:

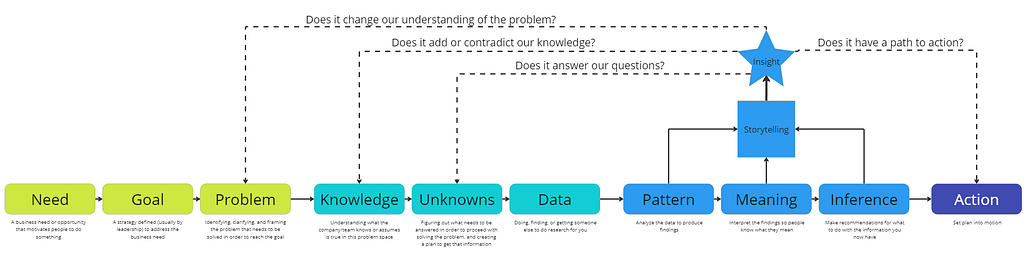

This is mostly the same image; I just made it linear to add a few extra items above.

Delivering insights requires you to take your findings (in the form of the data patterns, the meaning behind them, and the implications), and apply your storytelling abilities to make your audience feel like they know how to start addressing their problems.

An insight is not a sentence.

But a well-crafted sentence backed up by storytelling and data, crafted along with the right people and delivered in the right context can engrave an idea into the minds of the people who sign off on decisions and create movement within an organization.

That’s what you actually want!

It’s not to create the perfect presentation.

It’s to change hearts and minds.

How do you know if you’re going to be insightful?

You can’t just ask a stranger to confirm whether or not you have something insightful. And you can never guarantee what a person’s reaction is going to be.

But you can get a sense of whether you’re on the right track.

Take a look at your nuggets of wisdom, your takeaways, your “insights.”

Rewind to the first two steps of the process where you were figuring out the problem to solve, what your audience knows, doesn’t know, and assumes to be true.

Ask yourself the tough questions:

- Does it change your understanding of the problem?

- Does it add to or contradict what you think you knew?

- Does it answer the questions you had at the beginning?

- Is there a clear action or “next step” to solving the problem?

If the answer is “no” to all of these, you might need to keep looking or trying different ways to reframe.

You could feasibly follow the thread all the way back to the business need, but you’d be making a lot of assumptions along the way.

Pilot test your big reveal

To take it one step further, you need to step outside yourself. After all, you’re not the one that needs to have the insight. It’s your partners that you’re trying to influence.

Hopefully, you’ve invited them to be part of the process so they’ve been in the room with you figuring out what all of it means.

If 100% of your audience is completely unaware of what research you’ve been doing, you’re going to have a much harder time inspiring insights.

Before you share out to 100+ people, you should reach out to a few partners that you have good relationships with so they can preview the final form of the results ahead of time and give you feedback.

Since they were involved in the process, they shouldn’t be super shocked by the results, but they are great temperature checks for how impactful the findings and narrative are.

They can tell you what is new, what is confusing, and what is in the “no shit, Sherlock” category.

But interestingly, pilot testing might not even be necessary if your teamwork is good enough.

Insights are best experienced before the show

There’s an interesting assumption that insights get delivered from a podium, with a fancy deck, and to an unprepared audience.

That can happen, but it’s a big gamble.

The best case scenario for presenting your findings is that the most important people in the audience (the decision makers and those who influence them) were so involved with the research that they know almost exactly what you’re going to say and are already on board.

Basically, they’ve already had their “Eureka!” moment in the trenches with you.

Their feedback helped you craft the most impactful and relevant framing.

They already have thoughts or a plan about how to bring the plan to life and what needs to change on the product roadmap.

They’re in your corner and ready to exert their own influence to make things happen.

The only people that are hearing your findings for the first time are the people who will be along for the ride, or watching from a distance.

My insights didn’t change anything, what gives?

Chances are good that if you’re reading this, you’re one of the people who are responsible for informing, guiding, recommending, and supporting builders, leaders, and other decision-makers.

You don’t make business decisions, you guide others in doing so.

That means that you could do the best research of your life and have it lead to no noticeable shift in the organization.

This doesn’t necessarily mean your insight-building skills need work.

Even if you didn’t make any of these common mistakes, there could be external reasons why your insights failed to move the needle. Some common ones:

- It wasn’t the right time. Organizations operate in ebbs and flows. Maybe it’s the end of the year and people are rushing to finish projects, so your 5-year plan isn’t super compelling but would be if you’d given it at a different time.

- You didn’t reach the right decision-maker. You could give a talk so inspiring that you got standing ovations and tears from the crowd, and those people will go to work the next day as if nothing happened. One reason could be that they’re on your side but they don’t have the power or influence to do anything about it. You have to figure out who you need to convince ahead of time and make sure you reach them.

- The political stars didn’t align. Maybe the CEO just pushed for fixing the small things and making incremental improvements, and your big reveal of a blue-sky innovation isn’t landing well. Maybe the leader of whatever space you work in has his (let’s face it, it’s usually a male) own vision of what should be done and is only doing research to check a box. Womp womp.

The takeaway here is that you should do your best, but recognize that at the end of the day your responsibilities stop at the threshold of another person’s decision.

You are not responsible for other people’s actions.

For more on insights, check out these articles:

- Present actionable insights that stakeholders actually care about

- Finding research insights that don’t feel generic

- How exactly do you find insights from qualitative research?

- How you can create non-obvious UX research insights

- Why your research insights aren’t making an impact

I’m also a fan of this dscout article which gives a more step-by-step process for writing insights effectively. Here’s another from Answerlab.

Originally published at https://davidtangux.com.

Insights are not what you think they are was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply