Liminal Design is the opposite of the transactional design — different tools, courage and client interactions are required.

The beauty of Liminal Design is held gently by its intrinsic push towards deeper and more meaningful experiences. This sets it apart from efficient, ease-of-use and transactional design. For the liminal designer, this requires clarity about what that deeper meaning is. Whether this opportunity presents itself as an invitation to elevate the design discussion, or an elephant that just won’t leave the room, a whole new set of tools are now at your disposal. So are the hearts and minds of users. And the primal fears of your corporate client.

Liminal Design, as I see it, is the intentional creation of a separate space and narrative to hold a single experience we cannot have in the ordinary. It’s an “in-between” — or liminal space — because the experience is strung between our mundane reality and the bigger fiction it promises to bring us closer to. A church is an obvious and physical liminal space: a separate building to bring us towards the divine it represents. A cinema or theater is intentionally designed to let us leave the noisy reality of the bustling streets behind and, in the dark, immerse ourselves fully in tonight’s fiction. A short and stormy love-affair can be liminal. Simply sitting down to read a book is also a liminal experience: we leave one ordinary reality behind for a few moments, to immerse ourselves in the fictional universe of another narrative. Designing products and UXes for corporations can be elevated to do the same.

We create liminal spaces to offer experiences that are deeper and more memorable. But why the focus on fiction? Or as Salman Rushdie put it in Haroun and the sea of stories: “What is the purpose of stories, if they aren’t even true?” Good question! Because the liminal space isn’t ordinary, and therefore affords us a higher tolerance for ambiguity, conflict and speculation. When we were kids, we called it play: a necessary part of development. For adults, it’s hopefully still called play. In this sense, liminality is an attitude — a willingness to not see just what is, but to imagine what might be. This is suspension of disbelief. The very fact that fiction isn’t real, allows us to approach it differently: uninhibited by the real world risks to life and limb. These fictional experiences create very real emotions. It changes us, transforms who we are. Again, corporate experiences are no exception. Ralph Waldo Emerson put it succinctly:

“The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.”

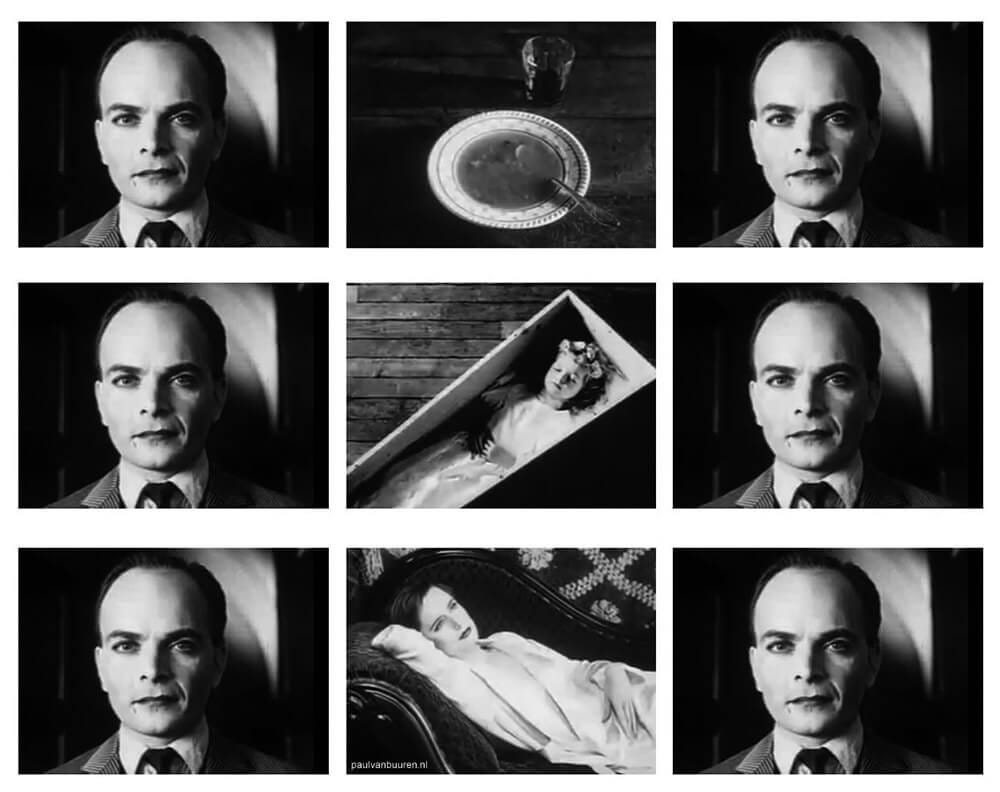

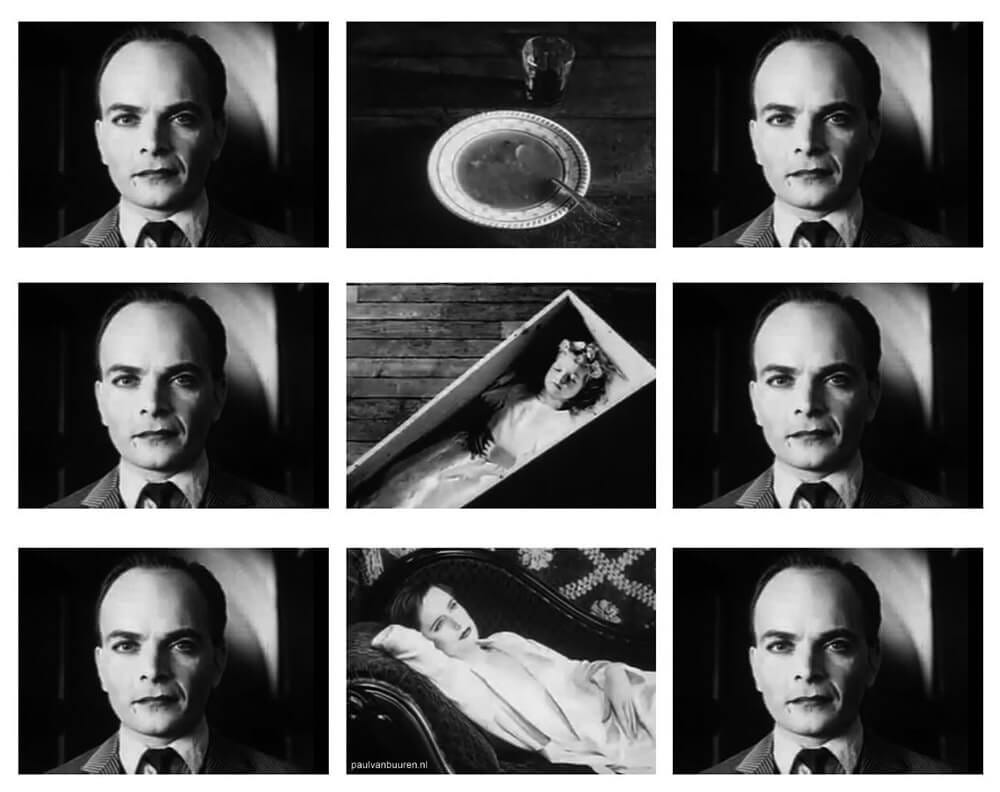

Surprise, Conflict and Mystery

But we are highly selective about what we spend our imaginary currency on. And we should be. This is also the key to commercial Liminal Design: we need a reason to engage that is important and tempting enough to bother leaving our ordinary reality to go explore the unknown without knowing what it will yield. If we knew exactly what we searched for, and were promised exactly that, it would be a simple transaction, and no imagination or liminality is activated, nor required. What all great stories promise is also what we need to promise for the liminal space: surprise, conflict, friction, temptation, mystery, and a glimpse of the sublime through a journey that always starts out very differently than it ends.

But at the same time, a large corporate setting, of course, is prone to primarily value transactions: repetitive and predictable behavior that can be streamlined to fit the needs of the commercial machine’s need to satiate an ever-growing appetite. Transactions are the opposite of liminality.

For example, Coca-Cola doesn’t really want you to think about what you are consuming: the more automatic it is, the more you drink and the more you buy. Starbucks wants you to buy lots of sugar and milk — quickly — and then leave the store even quicker. Enjoying the coffee house experience is a lost promise, tactically ignored — no Japanese tea house there. Zoom, the video conferencing platform, is well documented to fail in a multitude of respects at any real human interconnectedness because it is treating meetings like transactions. Technically speaking, this is very fixable if we allow it to take place in a proper liminal space. But then we would have less Zoom calls, less meetings, less participants on each call, and we would actually have to talk to each other.

Liminality vs. Transactions

So, there we are, stuck in-between the ambition of designing a deeper meaningful experience, and the commercial reality of what the machine demands. The issue isn’t that anyone is against meaningful experiences. At the heart of the matter is: what companies want simply isn’t that interesting. And what they claim to stand for in brand statements, isn’t actually what they are selling or even sincere. The liminal design process will highlight that. This should not be seen as a reason for defeat, but as the starting point for any creative work: to dig out the sublime inside the ordinary.

What good liminality promises is not just rational. It must be a siren’s call to adventure — a temptation that holds something more interesting than what regular reality can deliver. Only then will you have someone step away from the day-to-day grind and follow you into the fictional space. This is also the first phase of liminal design — creating narrative desire — to articulate the purpose and deeper promise of the liminal space. And it is often even more intimate: your own sincere work in finding deeper meaning in the corporate or mundane, and then in articulating , is the reverse journey you then offer the user. And just like your journey as designer is personal in how you present deeper meaning, so will it be for the user in how it is received and internalized. No liminal journey can be overly prescriptive or it will turn transactional. This is akin to creating and experiencing art and story.

The tools and processes available for the liminal designer are also different from those used when designing to transactional goals: say a more fuel efficient car, or a more easy to use interface. The first step to liminal design is to articulate the targeted narrative desire: what the experience promises that cannot be found in the ordinary. If this target or goal doesn’t require imagination to be activated, then liminality will not be activated either.

If we use the example with Zoom again, another product from the same company could be promising completely focused and immersive remote conversations for only two people at a time — this would be positioned as an antidote to the scattered video calls we are stuck on today and instead focus on what a real conversation is built of, and to elevate that.

Three Design Steps to Liminality

How would we do that with liminal design? First, like above, we make clear to the user that a deeper focused conversation is the expectation, and manifest this expectation through package design and positioning. We then design a clearly separate and distraction-free space, where users can have direct eye-contact, are able to read non-verbal cues and concentrate solely on their conversational partner. No interrupting notifications, messages or calls. This is never about replicating the day-to-day reality of the office — we are leaving it behind. It must instead be an abstract space intentionally pared down and optimized for the target narrative. Reference other abstracted spaces like museums, cinemas or churches — distinct and abstracted spaces where we are allowed to immerse ourselves in one single experience. When you get this far in the design process, the last step is to ensure that the fictionality of what is really a digital and remote experience continues to be immersive until the conversation is complete: to maintain suspension of disbelief. This particular remote presence example I have designed for, and know it can work.

Other real world examples worth mentioning are restaurants serving food in complete darkness to elevate and focus the experience on the culinary — to strip out most other sensory inputs. Another example is PTSD therapy using virtual reality therapeutically — a fictional, safe and controlled space to expose and spend time with a patient’s phobias to, say, fictional heights, or animated spiders etc. One very optimistic example — but yet to be realized — might be a new Amazon service, where instead of overnight delivery and the environmental impact that entails, we instead deepen the experience of select purchases by embracing the wait: as children, most of us remember saving up for or having to wait weeks to get a toy we really wanted. We might not recall much of the toy, but the anticipation leading up to it, we can still remember and feel deeply. This would be a good creative brief for the product design — the narrative desire — for this service. In all of the above examples, we have intentionally moved away from transactions to instead embrace memorable experiences — and that: is liminal design.

This framework and three step method is further outlined in the paper: Liminal Design.

In Story, Questions Always Trump Answers

The good news is that any deep liminal journey will likely do good in the world. It is always serious play. They cannot be prescriptive, and rely on sincere questions, surprise, hope and desires. Not answers. They only truly engage when they inspire, touch our hearts and stir our imagination. One should perhaps be careful with religious metaphors, but the story of the garden of Eden is low hanging fruit for any storyteller: your final design job is not to be a groundskeeper in paradise, but to disrupt the eternal comfort, safety and status quo. To be a trickster. To temp with another narrative that holds the promise and hope of something more complex and more interesting. There is no story of Eden worth telling without a little slither in the grass. It wasn’t just the fall of man, it was the birth of story.

Like all changes in behavior, it is not about bending small parts of a narrative, but rather providing new ones that speak of hope more directly to our imagination. There is no one single way to apply Liminal Design. In its wider acceptance as part of product development, I hope that the multitude of solutions it can offer will also lead to the unlimited inclusiveness of just as many profound experiences.

Johan Liedgren

Award-winning film-director, writer and consultant working with media and technology companies on liminal strategy, narrative and product development. http://www.liedgren.com / https://www.liminalcircle.com/

Liminal design and the corporate sublime was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply