We can learn about the design excellence of small nations by studying how Estonia and Singapore excel in innovation in the context of design festivals on the global stage

In a flurry of design festivals around the world, the ones that catch my eye are those from small nations. Happening every September, Singapore Design Week grew over the years into a series of conferences, workshops, and exhibitions, attracting names including Don Norman, Shigeru Ban, and many local designers. Yet, at the same time, and on a divergent path, I took the rare opportunity to travel to Estonia to speak at this year’s Tallinn Design Festival, titled Design 4.0.

At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be anything astonishing about these two festivals. After all, they were from two small nations, Estonia and Singapore. For Estonia, their population of 1.3 million determined their small size as compared to their Nordic neighbors. On the other hand, Singapore has a land area of not more than 275 square miles. To put that in perspective, Singapore is about the same size as Hiiumaa, an island in Estonia, which makes up about 2% of the total land area of Estonia. That makes Singapore one of the densest places to live for 6 million residents.

A case for designers to learn from small nations

Yet, being a citizen of Singapore as well as leading small design teams makes me a possible candidate to share why size doesn’t truly matter. On the contrary, being small actually helps designers and their teams blossom with quality. This was felt in my recent trip to Estonia’s design scene, as I drew parallels to deduce the similar factors of success in small nations. Their lessons could then be applied to smaller design teams within large organisations.

James Breilding, founder of S8nations and author of “Too Small to Fail,” makes a compelling case for small nations. He argued that the dominant measures of a successful nation, such as territorial size, military might, and natural resources, are now waning in light of increasing global economic independence due to the advancement of technology. The pandemic is a case-in-point when connectivity makes global commerce even more possible.

This is a world where small nations can thrive. In fact, according to 2023 reports, 8 out of the top 10 countries by GDP per capita in the world are small nations. Likewise for the IMD global competitiveness ranking. And the same for the top happiness countries in the world (although Singapore did not make it to the top 10, other than being top in Asia).

A designer’s perspective

Let’s shift our gaze to a designer’s perspective. Does size really matter when it comes to design teams? For that, comparisons will also have to be made. A common question that tends to be asked in any gathering would be as follows:

“How big is your design team?”

Some will take a puffed-up stance by claiming that their team has more than a hundred designers. Others will cast a sheepish look by rounding up their numbers to no more than ten designers. And the rest will claim they are the lone designer on the team.

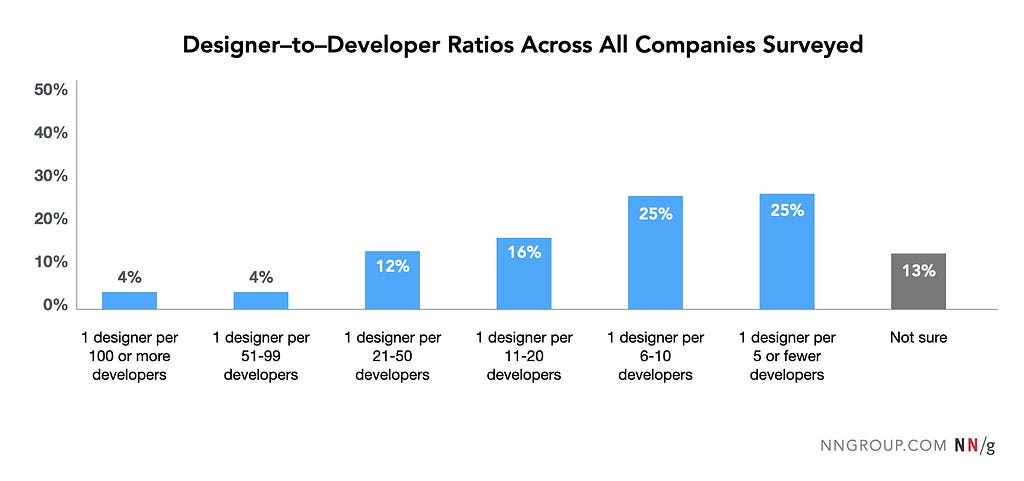

While it is common to compare size among design teams, perhaps it would also be essential to compare size within departments, squads, or tribes within companies. The lingo used is the ratio of designers to engineers in any given setting. NNG gives their recommendation, whereby every designer would work with ten other engineers in a 1:10 ratio. When you extrapolate that to the whole organisation outside of product development, the numbers further dwindle. Suddenly, there is a small island with designers next to a large land area filled with other professionals within the organisation.

We, as designers, can learn from small nations. My attempt is to consolidate a few lessons from my personal experiences at the design festivals and possible design applications, which will be characterised by the magical person emoji, 🧙♀️, as a tooltip.

Without further ado, here are three complementary factors:

1. Small nations are vulnerable. Thus, they practice modesty through partnerships to make things work.

When land is a limitation, so too are natural resources and the many advantages of a traditional economy, making small nations vulnerable to external conditions. Small countries like Singapore and Estonia rely heavily on trade, where the formation of bilateral ties is important to improve economic returns and create jobs.

Therefore, Singaporeans have a reasonable amount of diplomacy and equity when working with people. Partly because small countries do not have the same authoritative or historical significance in world events, many seek cooperation to get something done. These countries are not only multicultural in their neighbourhoods and workplaces, but they also conduct themselves with respect to others when working overseas. And when a small nation manages to foster modesty, reciprocity or a win-win situation can be created.

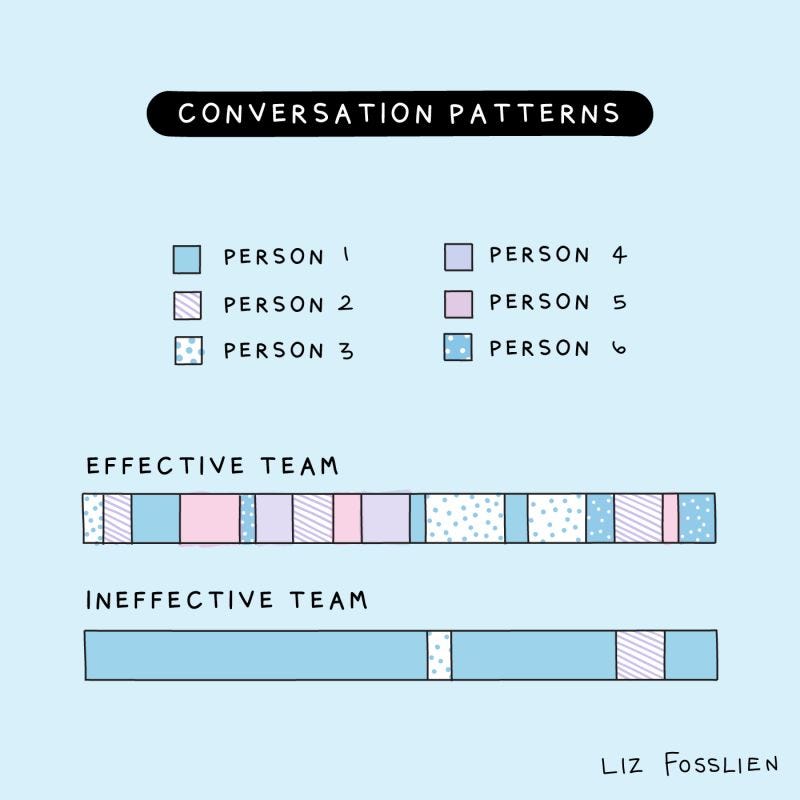

🧙♀️ Consider the size of the in-house design team to be a small, vulnerable nation. When designers apply empathy to their work by being human-centric, they can see things from the perspective of their users. Designers from small teams also tend to apply the same technique to their colleagues in other departments to practice reciprocity. By doing so, their social currency goes up, and they will get more gains by working with diverse yet like-minded people.

🧙♀️ Occasionally, go on an idea road trip. Designers seek new input as a form of inspiration for their work. Creativity develops when an innovator incubates a piece of work over time. In my case, my trip to Estonia had me discover new designs and implementations that could be brought back to my homeland.

🧙♀️ What if designers from Estonia went to Singapore to share their stories through their works? The reverse is also true when the outside comes in. When possible, design teams should create heterogeneity in their setup in order to bring diverse voices. Having a good mix of gender, ethnicity, and inclusivity isn’t a corporate policy. Especially when designing for a diverse set of people, design teams are effective when they embrace an outside-in approach.

2. Being small means being resourceful and trying something new

Because small nations cannot rely on their natural resources, many have invested in human capital, also known as the knowledge economy. As a result, a high proportion of small-nation citizens are exposed to various skills at an early age. They then become multifaceted and equipped with transdisciplinary skills. Thus, it is not uncommon to see individuals holding multiple degrees or working in diverse industries while honing their craft.

Singapore and Estonia are often referred to as small nations with good education systems. According to PISA 2018, Estonian general education is first in Europe and among the best in the world, and it has shown high rankings in many international studies. The Times reporter Rachel Sylvester wrote extensively about the success of the Estonian education system. One reason cited was from Andreas Schleicher, director of education at the OECD, saying:

“In Estonia, nobody would have this term ‘extracurricular activity’. For them, that is the curriculum.”

Through such a learning environment as well as an increasingly digital infrastructure, Estonian youths adopt an entrepreneurial spirit in their later lives. Evidently, it was clear when the number of design professors I spoke to practiced both research and craft concurrently. As Professor Reet Aus shared with me, she wouldn’t be seriously treated as a designer if she was solely working on research alone. She now both teaches at a university and runs her own sustainable fashion boutique store in Tallinn’s creative district, Telliskivi. So too are Singaporean designers, such as Professor Clement Zheng, who are known to wear multiple hats in their professions. It is no wonder these small nations are also labelled as startup nations based on emerging talents from within.

Speaking of startup nations, the same could be said of young startups, which mostly have humble beginnings in a founder’s garage or home. At the same time, these founders needed to wear multiple hats in order to start the business. Hence, a design founder could act as a UX designer in one instance, then as a marketer when coming up with a campaign before handling the operations to monitor the product uptake. The same goes for other members of the team who take on design roles.

🧙♀️ When designers see themselves as startup founders, they become more than single-minded specialists. However, rather than working in their comfort zone, perhaps even being T-shaped designers with a vertical specialisation and horizontal generalisation is not enough. As written in my previous article, Design 4.0, being an X-shaped designer reaps greater benefits because having a transdisciplinary mindset of picking two divergent skills and finding an application of them makes the designer more versatile. In other words, X-shaped designers ought to be good at what they know but better at what they don’t know.

🧙♀️ By carrying such a mindset, these designers are able to build new capabilities that can enhance their work. They too will not face obsolescence, especially when technology creates new types of work. One example would be for UX/UI designers to embrace AI as part of the work process. By learning new technologies and their applications, these designers will be better prepared when UX/AI becomes more prevalent.

🧙♀️ The same can be said of design teams that think like startups. With every new divergent skill picked, the design startup becomes an evolving, adaptable force that is resilient against organisational shocks while sharing the same operating model and design language.

3. Being small means knowing the boundaries so as to break the rules and take innovative yet measured risks

Singapore and Estonia cannot afford to be disorganised. Their speed to market will give their small economies a slight competitive edge to stay relevant. Thankfully, being young and small creates agility from within. Like clockwork mechanisms, frameworks, structures, and processes are in place so that these countries can achieve consistent output with minimal errors, allowing them to do more.

Singapore experienced early pains in their early days of independence when violent riots resulted in the loss of lives. Over the years, Singapore built a legalistic framework around the public interest of its citizens, giving them the unfortunate label of a “fine” country. The other side of the story is a sense of security, such that people feel safe. Likewise, Estonia is best known for its digital governance, transforming an outdated governmental system into an e-Residency—their human-centred, digital citizenship program—as well as digitising every aspect of government services, including voting.

These solutions may sound rather counterintuitive to other nations with bigger and older establishments. Yet they stem from a foundational concept known as disruptive innovation. The concept, which originated from the late Clayton Christenssen, states that a smaller company, usually with fewer resources, is able to challenge an established business (often called an “incumbent”) by entering at the bottom of the market and continuing to move up-market. The famous example of Netflix, which started as a DVD-by-mail service, quickly became noticeable when it shifted to an on-demand streaming model.

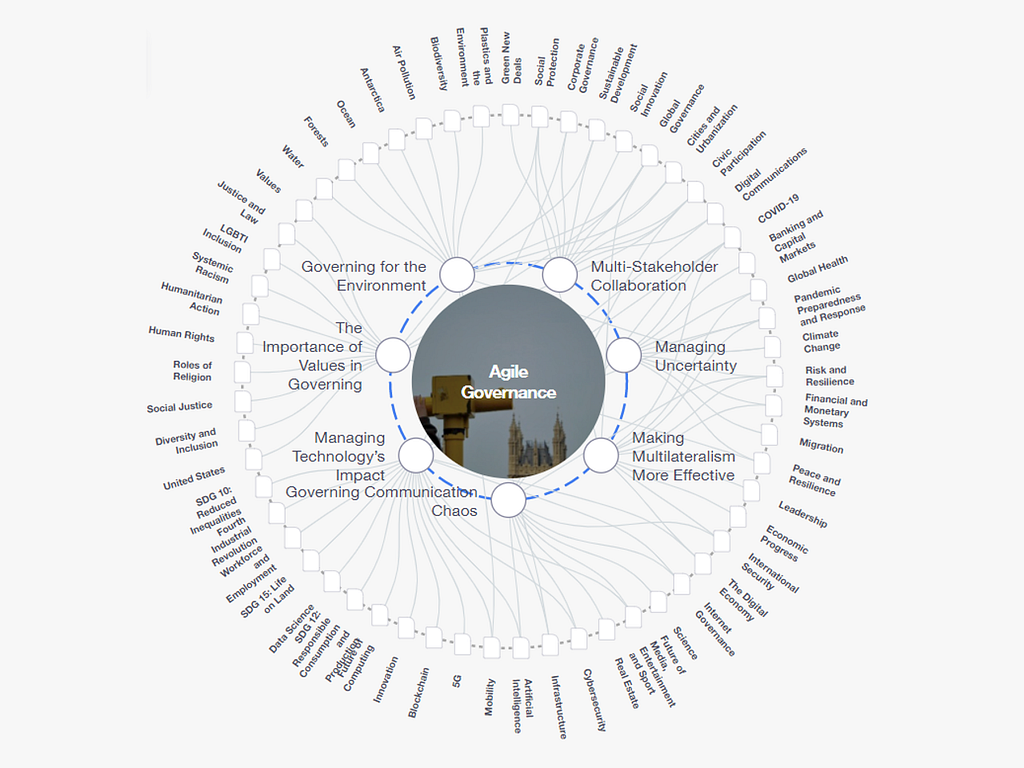

So what makes such innovation work? For small nations, having agile governance is essential. Once achieved, the next step is to innovate by rewriting the script and implementing it with calculated risk. Again, designers in such environments will thrive on creating innovative ideas supported by the infrastructure around them.

It leads me to conclude why so many innovative outcomes have come out of Estonia, from autonomous delivery robots by Starship Technologies to ride hailing and micromobility services by Bolt. Even fashion designers, such as Xenia Joost, choose to explore the use of NFT, the metaverse, and artificial intelligence. The future of design may incidentally emerge from such places.

🧙♀️ As designers, ask ourselves what our governing model is, both as individuals and within the team. What are some practices that we must uphold in order to produce consistent quality output? And how will our interactions with each other and with stakeholders ensure that our design processes are not forsaken but are carried out?

🧙♀️ Our organisations may have their own policies in place. Striking a balance between adhering to them and advocating for a new way of doing creates disruptive innovation. Strategies can be devised to bring two cultures together. For example, could internal fireside chats help to demystify the work ethics of designers? Or consider creating an in-house design exhibition for your organisation to physically experience and interact with your designs.

🧙♀️ Commit an 80/20 practice, where 80% of your time is to make the design team great by producing great work for the strategic priorities of the organisation. As for the remaining 20%, consider using them to experiment and push boundaries. Commonly known as bootleg innovation, these are bottom-up, non-programmed activities that do not come with the official permission of the responsible management but can create benefits for the company.

As a Singaporean living at the other end of the world, the journey to Estonia was simply unimaginable. Yet, what started out as a random chat with Ilona Gurjanova soon became a memorable time speaking to many designers on the topic of AI, design, and innovation. I too had a great time connecting with the many accomplished speakers from various design fields: Carlo Branzaglia, Haeun Kim, Hugo Jonasson, Reet Aus, Surya Vanka, and Xenia Joost.

After sharing many practical examples in my talk, the talk also reminded me of my unique design journey to Estonia. Through the vulnerability of not knowing what to expect from a foreign-speaking conference, I gain new insights and partnerships to make things work. I had to be resourceful by relearning new design skills like a startup founder again. And lastly, I took the innovative yet measured risk of going to a place where fewer Singapore designers would travel.

My encouragement is for all of us to start small and not forget why being small can also be considered a mighty strength of its own. Our actions may not only lie in our work but also in our daily decisions to make life a little more meaningful. I look forward to more opportunities to learn, grow, and contribute. Let’s keep the momentum going. 💙🖤🤍

Further readings:

Design 4.0: leading design in the new industry

- Bennett, Paul. “These Are the Big Things We Can Learn from Small Nations.” World Economic Forum, 9 Jan. 2023, www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/davos23-small-nations-singapore-new-zealand-iceland-wales/.

- Breiding, James R. Too Small to Fail. Harper Collins, 25 Nov. 2019.

- Christensen Institute. “Disruptive Innovations.” Christensen Institute, 2016, www.christenseninstitute.org/disruptive-innovations/.

- Education Estonia. “Reports: Estonian Education in International Comparison.” Education Estonia, www.educationestonia.org/reports/.

- Hunter, Marnie. “The World’s Happiest Countries for 2023.” CNN, 20 Mar. 2023, edition.cnn.com/travel/article/world-happiest-countries-2023-wellness/index.html.

- International Institute for Management Development. “Agile Governance and Good Access to Markets Boost Citizens’ Quality of Life -.” Www.imd.org, 19 June 2023, www.imd.org/news/economics/agile-governance-and-good-access-to-markets-boost-citizens-quality-of-life/.

- Kaplan, Kate. “Typical Designer–To–Developer and Researcher–To–Designer Ratios.” Nielsen Norman Group, 20 Nov. 2020, www.nngroup.com/articles/ux-developer-ratio/.

- Sylvester, Rachel. “How Estonia Does It: Lessons from Europe’s Best School System.” Www.thetimes.co.uk, 27 Jan. 2022, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/times-education-commission-how-estonia-does-it-lessons-from-europe-s-best-school-system-qm7xt7n9s.

- theWORLDMAPS. “Top 10 Countries by GDP per Capita, by Region.” Visual Capitalist, 22 June 2023, www.visualcapitalist.com/cp/ranked-countries-gdp-per-capita-2023/.

Design insights from small nations and their design festivals was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply