Conviction as a decision making superpower and exploring ‘narrative theory’

If you’ve been following these posts, you may have noticed the word conviction comes up quite a bit. In the particular case of navigating radical uncertainty, it’s the battleground between biases and heuristics (how we make irrational choices and act on flawed judgments) and naturalistic decision making (how these ‘flaws’ enable us to navigate complex, real-world situations)

Before we get into strategic decision making and the role of conviction, let's revisit the ‘confidence and intuition’ debate.

As we briefly covered in a previous thread, we see in this 2010 interview between Daniel Kahneman and Gary Klein that the two are at odds on the topic of confidence — specifically, overconfidence.

They both agree that overconfidence is detrimental, but Gary Klein, echoed by Gerd Gigerenzer and supporters of ‘Ecological Rationality’, makes exceptions for high-validity environments (e.g. medicine, coaching, aviation) where leaders have deep domain expertise. The most common example was highlighted in Malcolm Gladwell’s book ‘Blink’ about a firefighter who intuitively made a snap decision to evacuate a building by ‘just knowing’ the floor might collapse.

Regardless of this disconnect between over-confidence and intuition, these topics have been covered by countless books authored by various researchers across economics and behavioral science — Richard Thaler, Cass Sunstein, Herbert Simon, Tali Sharot, and Richard Zeckhauser to name a few.

Through this research, we know a great deal about how individuals make judgments and choices — even in some limited real-world scenarios where information and time are limited (e.g. the firefighter example), but this still doesn’t effectively represent ‘radically’ uncertain environments.

Other researchers, practitioners, and academics in the overlapping worlds of strategy and decision making warn against directly translating learnings from decision making observed in a lab to real-world strategic decision making.

Much mischief can be wrought by transplanting this hypothesis-testing logic, which flourishes in controlled lab settings, into the hurly-burly of real-world settings.

What factors differentiate strategic decision making?

In his book Left Brain, Right Stuff, Phil Rosenzweig argues there are a few primary factors unique to strategic decision making — Influence, Competition, Feedback Loops, and Conviction:

- Influence: How we act and intervene can influence the outcome (He argues we often have more control than we may realize)

- Competition: In this environment, success is relative, not absolute

- Feedback loops: Time to learning is often long and lagging

- Conviction: Perception and credibility are important

He argues these are the primary factors that cannot be duplicated in a lab and are even difficult to observe in real-world situations — especially since the context for each decision is often unique.

Many of these factors feel intuitive — but what is conviction? How is it different from the overconfidence behavioral scientists warn of, and why is it important in this environment?

First, we can try to make a distinction between the environments:

- Normative Environments: where there are clear actions and subsequent outcomes that are designated as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or impermissible. We have a clear idea of what ‘should be’ vs what ‘shouldn’t be’.

- Radically Uncertain Environments: where outcomes and utility are unknown, the relationship between actions and outcomes is not stable, and many potential options/scenarios can’t be effectively modeled or predicted.

We might say that these normative environments are high validity, but uncertainty can vary. For example, poker and warfare are high validity environments (where one right or wrong move influences the next and feedback loops are tight), but also highly uncertain environments — luck plays a significant role.

Most research observes situations on some spectrum of these ‘normative environments’, but these don’t effectively model radical uncertainty — a low validity environment that’s also highly uncertain (business, politics, or something like space exploration)

We use the term radical uncertainty to refer to equivocal situations in which uncertainty about the outcomes of actions is so profound that it is both difficult to set up the problem structure to choose between alternatives and impossible to represent the future in terms of a knowable and exhaustive list of outcomes to which to attach probabilities.

David Tuckett, Milena Nikolic: The role of conviction and narrative in decision-making under radical uncertainty

So how do we think about strategic decision making in these environments of radical uncertainty? Strategy, management, and leadership practices have been widely explored and debated, but as neuroeconomics and the study of decision making is still a nascent field, relatively little work has been done on the subject of strategic decision making in complex, uncertain environments.

“Radical uncertainty cannot be described in the probabilistic terms applicable to a game of chance. It is not just that we do not know what will happen. We often do not even know the kinds of things that might happen.” — Mervyn King, Economist: Radical Uncertainty

In the work that has been done, it’s evident that conviction plays a major role in our ability to operate in these environments and inspire others to do the same.

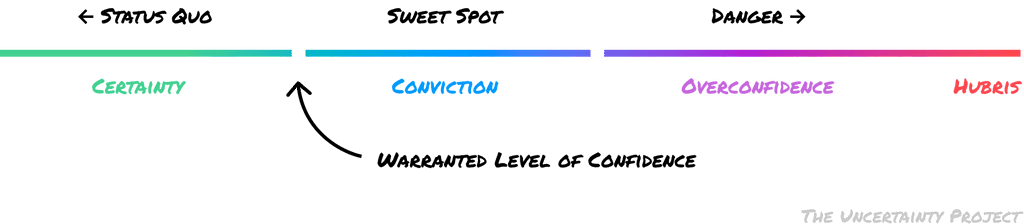

We’ll dig into a few of these studies that explore this phenomenon, but first, we just covered this foundational argument around confidence (and overconfidence), so how do we differentiate conviction?

Conviction vs Confidence

Because they are easily conflated, it’s helpful to clarify confidence and conviction:

- Confidence: The state of feeling certain about the truth of something.

- Conviction: a firmly held belief or opinion

The primary difference is that confidence is relative to certainty while conviction is based on beliefs — regardless of evidence or probabilities. If we’ve learned anything so far, it’s two things:

- The pursuit or illusion of certainty is paralyzing and dangerous

- Strongly calcified beliefs and assumptions are the enemy of progress

“When I find new information I change my mind; What do you do?” — John Maynard Keynes

In tech especially, we glorify overconfidence — “Strong opinions, loosely held” (a popular quote by Jeff Bezos) exists in some fashion in many ‘company principles’ — but this way of thinking can have detrimental effects if it’s giving a hall pass to overconfidence.

In short, it assumes we’re good at challenging our beliefs, objectively processing information, and viewing reality for what it is.

But we’re not. By default, we anchor to our initial assumptions, intake and share information through a strongly biased filter, and construct our subjective reality in real-time.

So we need to find a sweet spot and put guardrails in place that combat overconfidence, challenge assumptions/beliefs, and actively avoid the comfort of the status quo (or regression toward the mean)

As an interesting aside; It’s well-studied that our memories are not accurate representations of the past, and some studies suggest that our memory recall may be more optimized for simulating the future than remembering the past. The functions that drive our ability to do this ‘mental time traveling’ are rather similar.

The capacity to hold conviction in the face of uncertainty

Peter Drucker famously said:

“Whenever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision.”

There’s something very human about the ability to succeed against all odds. There is, of course, danger in these intoxicating and heroic stories — they often dismiss base rates and fall victim to survivorship bias, but nonetheless, conviction plays an instrumental part in the emergence of innovative ideas and ‘bold’ decisions.

Sir, the possibility of successfully navigating an asteroid field is approximately 3,720 to 1

— C-3PO

Even the perception of conviction is meaningful. We gravitate towards confidence not only because it’s inspiring, but because it’s a herd heuristic that allows us to make fewer, harder decisions on our own. It’s a lighter cognitive load to trust than it is to construct our own convictions.

There are a few interesting studies that suggest a model for thinking about conviction and strategic decision making:

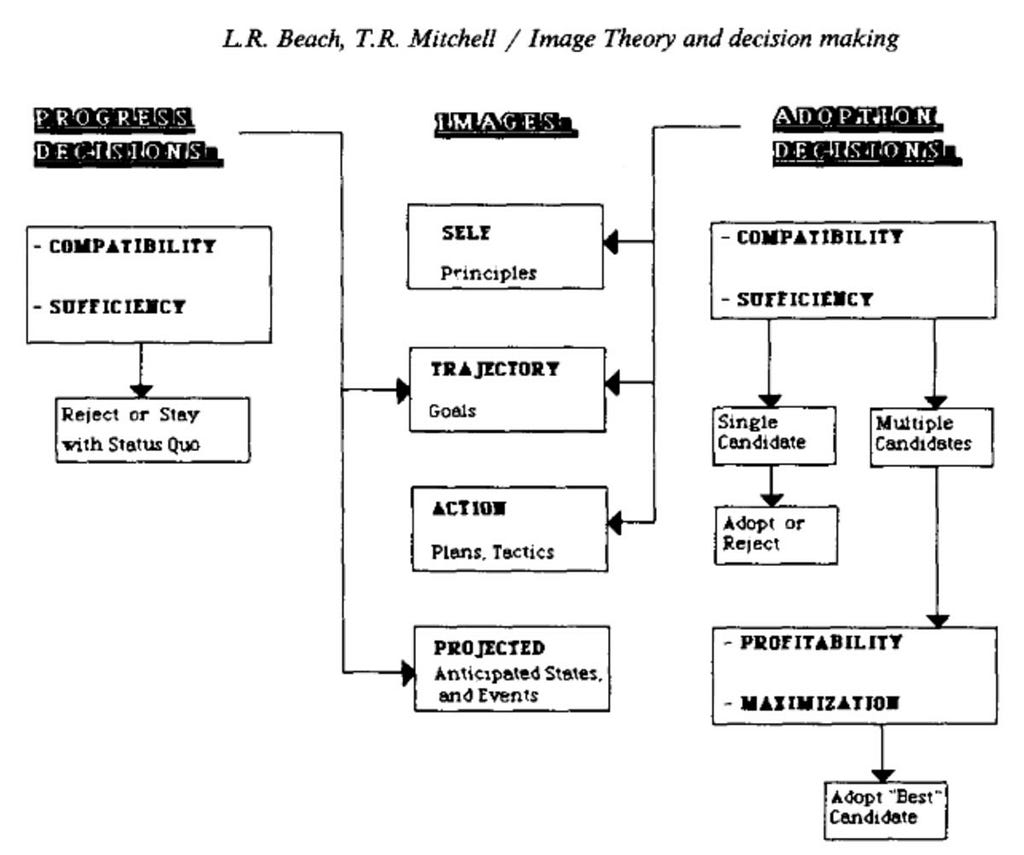

- Image Theory: When we think strategically, particularly to achieve some goal, we create mental images: The self-image, the trajectory image, the action image, and the projected image.

- Conviction Narrative Theory: Enables actors to draw on the information, beliefs, causal models, and rules of thumb situated in their social context to identify opportunities worth acting on, to simulate the future outcome of the actions by means of which they plan to achieve those opportunities, and to feel sufficiently convinced about the anticipated outcomes to act.

Image theory has been influential in theorizing how mental images might play a major role in how we model strategic decisions — essentially creating a picture of our beliefs and values, what success looks like, our action plan, and potential ways the plan unfolds.

This is counter to the idea that we analytically reason our way to conclusions and instead, compare new information to these mental images. Below we can see how Lee Roy Beach represents two types of decision candidates (progress or adoption) challenging the mental images and deciding whether or not the model accepts and adopts new updates.

Now layering in Conviction Narrative Theory, we start to see how these mental models build narratives that we then act on (and continue to act on) among a constellation of changing variables and new information.

- Narrative: A process that allows us to construct the everyday meaning of events and happenings along with their causal implications.

- Conviction: The subjective confidence to act (and often to carry collaborators with you)

In Conviction Narrative Theory, a preferred narrative for action emerges through conscious deliberation influenced by an overall appraisal of the approach and avoidance feelings evoked by every chunk of the narrative predictions about outcome that form the narrative. So, the credibility of the information contained in the narrative for action, the implicitly and explicitly held beliefs that govern expectations, the decision rules guiding inference, search, and checking that are adopted, the explanatory causal models used in simulating the outcomes of action, the various action tools selected, etc., all evoke emotions.

A preferred and conscious narrative of the outcome of action emerges from the evaluative process, in part explicit, but much of it implicit and automatic, to evoke a state of action readiness.

It’s interesting that both of these theories build on research suggesting it’s incredibly difficult to update the underlying beliefs and assumptions that subconsciously drive our decision making.

We, as individuals, vary on our threshold for willingness to hold convictions in the face of imperfect or contradicting information, as well as our tendencies to seek certainty (or fabricate the feeling of certainty). It’s common to point out individuals that are more ‘confident’ even if we’re conflating the term.

But instead of dismissing conviction, that by definition is often contrarian or counter to existing information, we may think of it as a unique and powerful factor when making decisions in radical uncertainty.

And also deeply human…

The ability of human actors to draw on feelings of conviction provides an advantage that is unavailable to a computer generating and optimizing scenarios.

“…While a computationally competent outside observer may be unable to identify secure grounds to support a particular narrative of the future in radical uncertainty and so to commit to a particular decision, a human decision-maker can feel sufficient conviction to act.”

— David Tuckett, Milena Nikolic: The role of conviction and narrative in decision-making under radical uncertainty

Beware of escalation of commitment.

We’ve started to explore the downsides to holding onto convictions too tightly for too long and crossing into overconfidence and hubris — Annie Duke, in her book ‘Quit’ extensively covers the risks of escalation of commitment and holding on to sunk costs too long.

There’s plenty of nuance in this topic and a lot more to dig into here that we can cover in the future!

This post was originally featured on the Uncertainty Project

The role of conviction and narrative in strategic decision making was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply