As a UX research consultant in Japan, I’ve worked with a wide variety of international companies looking to test their products with…

From local to global — how to serve a worldwide customer base

My mission to understand the world, its cultures, and its people has led me to French-speaking Africa. Cameroon, to be precise. I am here for two months to help an NGO that works on improving awareness and treatment of mental health in the country.

Next to my volunteering, I want to find out how Cameroonians, and people in surrounding countries, experience the tech world.

How do they use their apps? What role does tech play in their lives? And most importantly, which Western-designed technologies hinder them from having a satisfactory UX?

I am fortunate to be able to speak French, so I don’t have to live in the typical ex-pat bubble you can find in each capital city. I live in an authentic neighbourhood, buy groceries at the market, eat street food, and hang out with the locals. And, of course… commute and go to the office.

I investigated daily online routines and frequent struggles. I spoke to my location connections. They come from a variety of backgrounds and disposable income groups. I also conducted guerilla interviews on public transport. I then reached out to a few local UX specialists and met with them. All these people were surprisingly consistent in their answers. They all suffer from and recognise a few main problems.

I verified the content of this article afterwards with 5 individuals, and they were impressed by the accuracy of the conclusions.

Let’s go over the findings.

Just be aware: Africa is a vast continent with many different cultures. Each country is unique; within most countries, different ethnical groups and tribes live together. Cameroon alone can already be considered a multicultural society.

Although many West and Central African countries have cultural differences, most of the issues I described in this article still apply to the Central and West African countries.

1 — Bandwidth

You might expect that mobile internet is an issue in some parts of Africa. You are right. But it’s different than you perhaps think.

Cameroon has three major phone network companies. Orange, MTN, and the government-run brand Camtel. The quality of network coverage varies throughout the country.

Some regions have very poor connections, but the coverage is really stable in the main cities, Yaoundé and Douala. Houses usually don’t have a fibre connection, so the mobile network is the only option for most people.

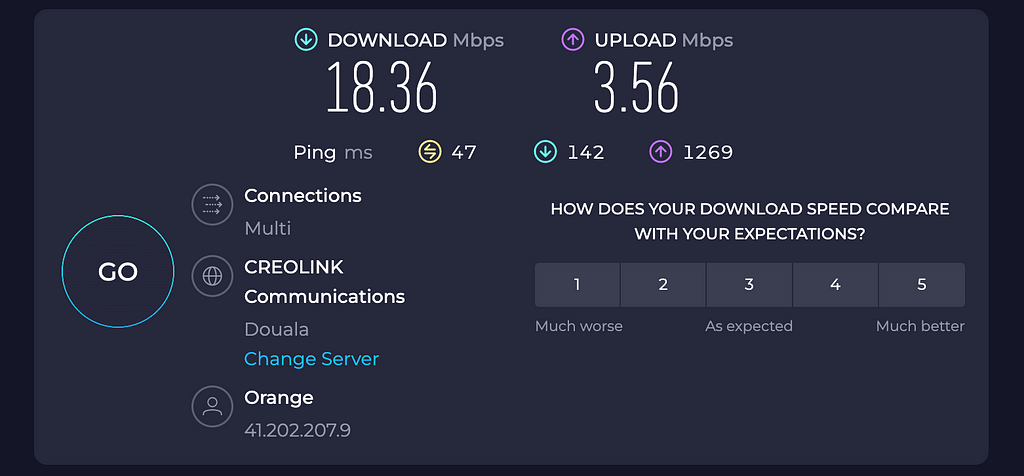

I use a Camtel and Orange sim card, and both networks' speed is impressive. I have stable 4G networks and am constantly above 10 Mbps.

Most educated people live in the two big cities, so internet speed isn’t a problem for them. The biggest issue is the price of the data.

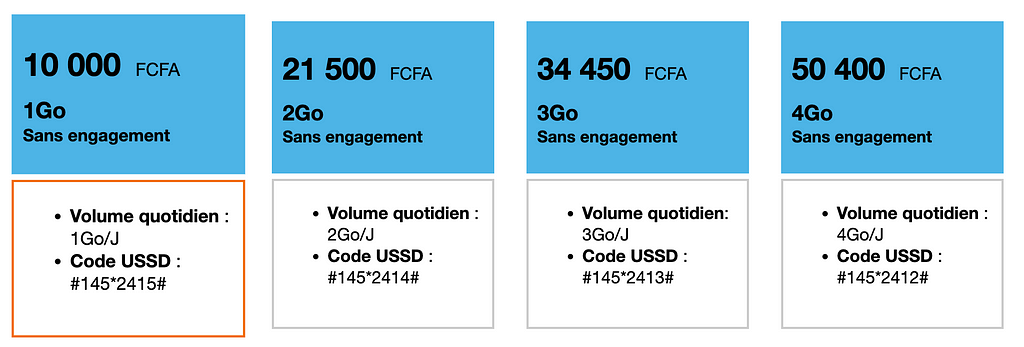

Orange offers 1 GB of data per day for 10,000 FCFA per month. This is around 15 euros (or dollars). Camtel’s prices are slightly lower, but their network coverage is less good. MTN is more expensive.

The average salary in Cameroon is a little more than 100,000 francs (150 euros) per month, and the legal minimum wage is around 37,000 francs (56 euros). Like in most countries, the standard of living is higher in the capital. In Yaoundé, a salary of around 250,000 francs is not uncommon.

you can see that the cost of internet is disproportionate to a regular local salary. Most people can barely afford mobile internet. Those who can, need to be careful with the data they spend.

Some people use flight mode for a part of the day to limit their usage. Cameroonian influencers even started a movement called Mode Avion, which encouraged everyone to enable flight mode for 2 hours of the day to express unhappiness about the prices.

My personal experience

I use the 3 Gb/day orange plan. This costs me 55 euros per month. This is much, much more than what I pay in France and unaffordable for the locals.

I attended a virtual conference and streamed the talks in HD. There was no option to change the resolution. I didn’t need HD, but the system automatically chose the highest resolution available. It burned through my daily data allowance quickly.

I need to plan my Zoom calls strategically because I can’t have more than 1 call daily.

I can send an SMS to my phone provider to request how much data I have left for that day. Everyone is doing this constantly, and so do I. Having to think about how much data you spend is a pain.

This illustrates how Western design influences the local user experience. Streaming a video on Facebook is technically not a problem. It loads fast, but people just can’t afford it. If you see how much data many apps spend by default, and what one GB costs, you can imagine how that influences adoption rates.

2 — Payments

Cameroon has a big “informal market”. Many transactions are still done with physical money. Credit cards are not widely adopted. What’s problematic is that there’s a severe lack of coins.

It might sound surreal, but the country doesn’t have coins because Chinese people literally come here to steal them. They make jewellery from its material.

The Chinese collect coins via a network of slot machines, strategically installed at bike taxi points. Rides are paid with coins. The drivers then use these machines, hoping to earn a bit more.

You can’t make this up. The local police seized 2 million francs in coins at someone’s home. This person must have had very, very deep pockets.

So how does a coinless world work?

The smallest bill is 500 francs. I have a problem if I want to pay at the supermarket when the total amount is something like 2,275 francs.

Supermarkets have biscuits at the cash register that cost 25 francs. They beg me to buy a few to round up my total amount. They simply don’t have change. I often solve a part of this issue by asking for a voucher to get a crêpe at the boulangerie in the same supermarket.

How is this related to tech?

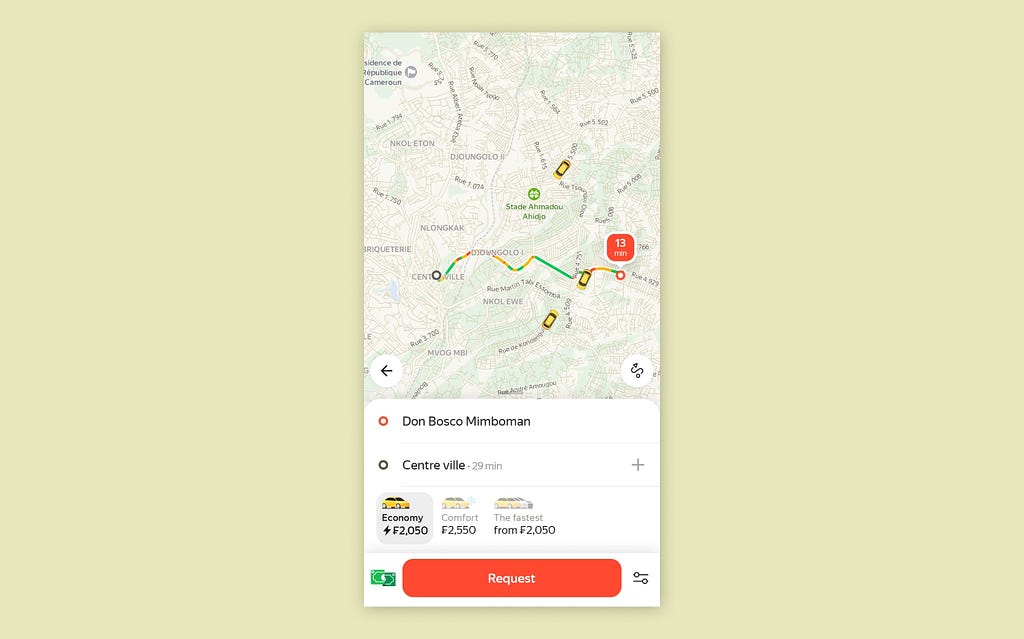

Cameroon uses Yango, a Russian-run Uber / Lyft / Bolt / Grab equivalent. In this app, I have to pay for my rides in cash.

Yango obviously uses an algorithm to define the price. I am often expected to pay something like 1,150 francs. This is just insanely annoying because I don’t have coins.

I solve this by walking in the direction I’m headed and ordering the taxi when I only have to pay 950 francs. This way I can just pay with a 1,000 francs bill.

Challenges like these can be easily solved in the app by making some rides more and others less expensive. Round up the prices so everyone would pay the same in the long run. You wonder if Yango conducts UX research on the ground.

How do Cameroonians pay for subscriptions if they don’t use credit cards?

A concept called mobile money is the most common way to wire money. The system works quite well.

There are small mobile money shops and stands all over town. Seriously, everywhere. At these places, you can give money that will then be put into your phone number. Your phone number basically becomes your bank account.

As you can see in the photo, mobile money is run by the telecom companies, Orange and MTN. This service is linked to banks, allowing users to move money between their phone numbers and actual bank account if they have one.

Many shops accept mobile money payments. You can pay by sending an SMS or scanning a QR code. You can also send money to other people’s accounts. This is how I pay the rent for my flat.

This is also how people pay for their phone subscriptions. Every month, they walk to a shop to transfer money to their phone number and send an SMS. This is for people that get their income from the informal cash-driven market (e.g. street vendors, small shop owners, etc.). Employed people receive their salary in their bank account.

What about credit cards?

They have become more common. But implementation and adoption are very slow. Local fin-tech startups like PaySika are trying to give people access to financial services like credit cards. They face challenges from the government and the BEAC (Bank of Central African states). These institutions can’t cope with the speed of this innovation.

Another issue why credit cards are not often used is the mentality of the people, but I will discuss this later in this article.

3 — Address unknown

Food delivery apps or webshops aren’t widely used in Cameroon. The biggest issue is that the delivery people won’t be able to find the recipient's house.

Most streets don’t have a name, but a number instead. The problem arises when the delivery person enters the street. Houses don’t have numbers, so they can’t find where to deliver the order.

The government is in the process of allocating unique numbers to houses. However, this is firstly done in the cities and is a process that advances slowly. There’s not much faith that this will actually be a successful process. “I think we need an app that assigns digital address numbers to houses for them to be located,” is what one of my local connections suggests.

Pick-up points also don’t exist, so mail-order systems are not an option for the moment.

However, food delivery apps Gozem and Chrono Foods recently arrived in the biggest cities in the country. In the app, you can specify where the food needs to be delivered.

Landmarks are often used as points to orientate. I don’t live in street 4,492. I live in the yellow 4-story block of flats opposite le chateau d’eau.

Many companies use WhatsApp to conduct their business. This is not unique to the food industry or the African continent. I’ve seen it a lot in Asia too. WhatsApp allows companies to work around limitations like a strict calendar booking system (time can be “fluid”) or a street or GPS-based address.

4 — Not the latest phones

Most Cameroonians have limited purchasing power. On top of that, electronics are much more expensive in Sub-Saharan Africa than in any Western country.

High transportation costs, customs duties, and other unidentifiable aspects, significantly increase the overall cost of the products. It’s common for locals to ask Western visitors to bring electronics from abroad. This will save them a lot of money.

In fact, I also travelled from Europe with a laptop, external hard drive, and headphones, which my connections needed.

It’s thus very logical many people use older phones.

This leads to compatibility issues. Some apps don’t work. Also, battery life can be reduced. I see many people carrying a charger and plugging it when they find a socket in a restaurant. The country also suffers from frequent power cuts, which adds to the problem. Some shops, which have generators, provide recharging services.

Performance issues and less storage are other aspects that influence the User Experience. Apps like Facebook Lite are really helpful for many people. These apps are less heavy, so they occupy less phone storage and consume less data.

GPS is not always accurate on older phones. When I order my taxi, the driver always calls me directly afterwards to confirm my pick-up location. It’s a routine for them. Therefore, I always walk to an easily recognisable landmark, like a hotel, to be able to explain to the driver where I am.

5 — Resistance to Change

The geography of Africa can be complex to understand. A part of this results from the colonist countries drawing arbitrary borders, straight through the habitat of ethnic groups. Many contemporary conflicts come from not diligently divided territories.

This is no different in Cameroon. The border regions are conflict zones. The country has many tribes and two main languages: English and French.

The cultural influence of former emperors France and Britain is very visible today. Although English-speaking people are a minority, they are overrepresented in — for instance — the tech world. Almost all UX people I met here are native English-speaking people.

The cultural dimension of uncertainty avoidance is at the core of this phenomenon. Anglo-Saxon countries are low on uncertainty avoidance and therefore deal efficiently with change. Most Catholic countries, including France, prefer to avoid uncertainty. This leads to less quick adoption of innovation.

These philosophies are deeply embedded in people’s behaviour. The former Western empires have significantly impacted African administrative and education systems and the ways of living in general. Even today, French national television is the default channel in hotel lobbies and restaurants. The French culture continues to have its impact.

When combining a desire to avoid uncertainty, and a less technically developed life in general, you can understand that many Cameroonians aren’t eager to “risk” changing their habits.

They feel comfortable having physical money in their hands. The idea of moving money to a virtual credit card is too much for them. Adoption rates for concepts like these are really slow.

I obviously can’t generalise, but across the board, the English part of the population is more open to trying new things and should be seen as influencers for the rest of the country.

When introducing new apps in the West-African region, a significant amount of attention must be put into creating trust with the users and gradually onboarding them to the product's full potential. Take them by the hand. Slowly.

We can’t take for granted that the locals directly understand digital conventions that are normal to us.

Why should we care?

1.5 billion people live in Africa. It’s the second most populated continent in the world. Demographic simulations predict that the African population will grow much faster than in any other part of the world. Especially in Cameroon’s neighbouring country: Nigeria.

It clearly shows a commercial opportunity for Western companies. This is perhaps something that convinces the C-suite. But more importantly… these people have the right to connect as much as we do.

The government and companies like Orange keep the price of internet high, cutting off many people from a fundamental human resource: information.

In addition, credit card payments barely exist in Cameroon, so there is no incentive for content creation. You won’t be able to monetise your Medium account. Uploading a Youtube video is too expensive.

The current AI tools are highly biased towards Western standards because most content these models process is created in the West.

If we want to help the local people develop their knowledge, skills, and contribution to AI and the world as a whole, we should include them in our digital ecosystem. In many aspects, the Central-African region falls behind. They suffer from bureaucratic inefficiencies. Companies are often run in a less practical manner. People deal with power cuts every day.

This is not a reason to treat them condescendingly. On the contrary. Many of these countries lag behind because we — the West — have depleted their natural and human resources for ages. In fact, we still do it today. We don’t only rob them of their talent and oil, but apparently, also of their coins.

The least of our moral responsibilities is to provide adequate access to internet and to our apps. Young people are motivated to learn. They should be able to consume the knowledge we already put out online. Teenagers can’t watch Youtube videos because the data is too expensive. They can’t follow a Udemy course, even if this course is free.

From a commercial perspective, we should also be aware that all countries have significantly developed areas too. You can find malls, upscale restaurants, and hipster coffee bars everywhere in Cameroon, and other countries in the region.

West and Central Africa has much commercial, intellectual, and entrepreneurial potential. We shouldn’t ignore this if we want to create global products. We can’t serve the entire world from our Silicon Valley, Singapore, or London bubble.

We need to be aware of what’s happening in the regions we want to serve. As we’ve seen, small things like adding a resolution choice to a video streaming service or a different payment method to a taxi-hailing app can significantly improve people’s lives.

The easiest — and cheapest — way to inject global knowledge into your team is by recruiting people who understand these specific markets. Even if you can’t conduct UX research in all countries, someone who lives there brings a world of knowledge.

They can help you make your product more suitable for the local market. They can acquire international experience and afterwards apply this to domestic businesses, which is also very valuable for the local industry.

Give local UX designers a chance in your company. Not to deplete the country of its talent, but to help the region and your product grow.

Win-Win.

Gagnant-Gagnant.

Merci.

If you want further explore cultural differences in product design, check out my article on cultural differences an UIs.

How does our cultural background influence product design?

5 reasons why apps fail in some African countries was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply