The system strikes back.

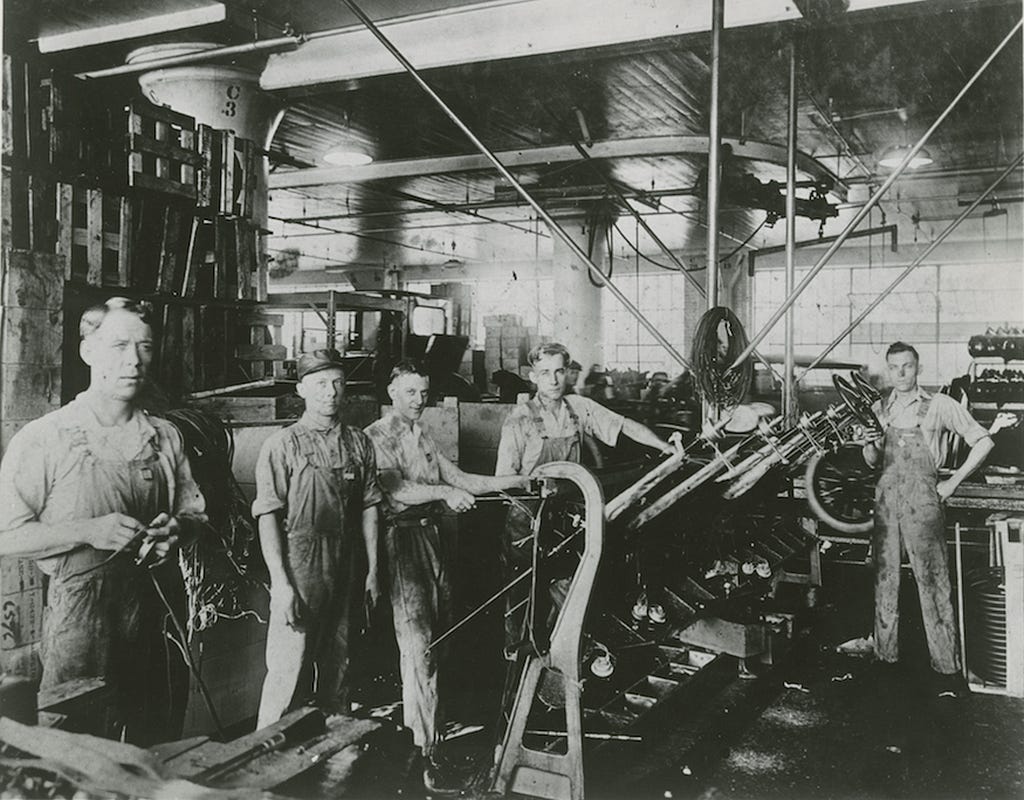

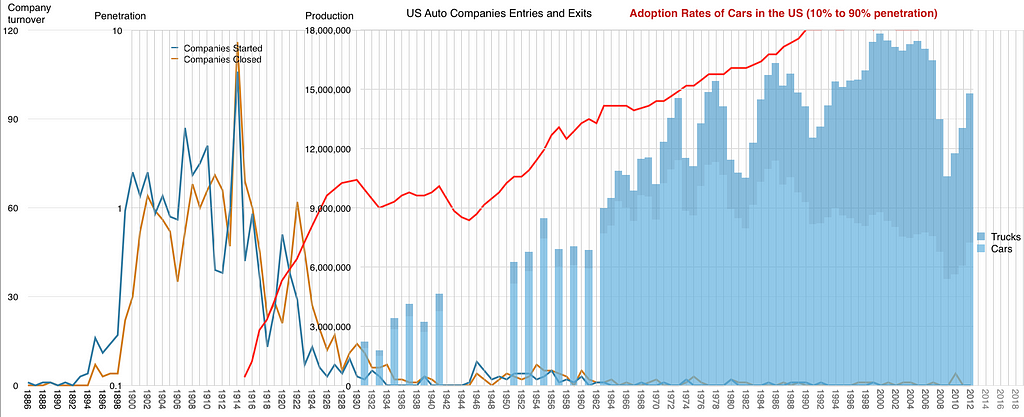

In 1895, at least 1900 different companies were producing over 3,000 makes of automobiles. These automobiles varied in size and shape, in manufacturing style, and in energy sources — electric, gas, oil. The intent was fairly aligned — reduction of energy spent on human-sized transportation– but the outputs were wildly different. The creation of a new ecosystem of product always has its heady experimental days of figuring out what the Thing is, before a form factor generally gets decided upon. By the time Henry Ford built his Highland Park factory in Chicago, ushering in the era of mass-produced automobiles, about 20 years had reasonably passed since the boom of widespread experimentation, and the form factor settled into rigid shape. At that point, the process moved from experimentation to scaling and evolving. There can be minor breakthroughs in underlying technologies and execution, but once it is widely adopted, very rarely does a general product form factor change from a functional level. A mop is still a mop. Countless testing has worn a groove that can withstand pressures.

This is not, prima facie, a bad thing. The role of design is a role of service. A solution that solves the problem in a complete way is the finale every honest designer desires. This presumes, however, that the final form is one that serves the user best. Unfortunately, in a for-profit system, the form factor usually ends up being the form that makes the biggest players the most money.

I think a lot about trust in my work. In general, it is easier to be good at my job when trust is high. While our engineering friends can rely on the specific outcomes of engineering to engender the trust by things like performance, product and design is a trickier affair: it requires a longer tail of relationships, a longer timeline of working before outcomes become tangible, and a leap of faith that our solutions, (even testing validated ones!) will land on the other side. Like the great Erika Hall says, design is about intention, and designs are tasked with examining the intention of choices, hopefully with user outcomes in mind. At least that’s what I have carried about in my head for the past twenty years.

But design is not really about intention or trust anymore, it’s about output.

As much as it pains me to say it, before the FAANGs, everything was different. In previous iterations of design in the software development lifecycle at massive scale, huge deployments were gated and yearly (or biyearly) affairs that had launch days and pages of release notes (games still work like this, for context). This meant that internal design teams could experiment with what works before being put under the gun of deployment. The rapid scale of a live product like Facebook (different in perception than a service like Google and related apps, at the time) meant that they had to build the scalable, performance-oriented web architecture that we know today. Along with React and the concept of a ‘component system’, Facebook cut into stone the nascent idea of constant delivery as a way of deployment.

The rise of the enterprise-scale design system, embedded in a philosophy of constant delivery quickly followed suit. The Facebook early mandate for its design team probably looked a little something like:

- Scale and don’t break

- Service as many different users as possible

- Don’t get in the way of engineering

Taken alone, each of these is a valid goal for a large enterprise entity, scaling up as fast as possible to please its capital-commanded mandate.

From an engineering point of view, this was efficient.

From a service point of view, it made sense.

From a shareholder point of view, it was valuable.

From a design point of view, it was catastrophic.

The value of design is the value of creativity, of problem-solving through nimble thinking, and of outside perspective. If production is the ice, then design is the water — made of the same stuff, but inchoate, able to flow into hidden spaces. It is trust in a process that will allow you to go down dead-ends and come back up to find the proper solution three months from now. If your role as an enterprise designer at a huge enterprise organization is to somehow get your hands around 10,000 slightly-off patterns, systemized templates start to seem awfully appealing. But is that…design? I’m not too sure.

“I used to be in design, but now I’m product.”

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that around 2013, the term “product” arose and began to be attached to titles, and as a role itself. “I’m not a designer, I’m a product designer.” “I used to be in design, but now I’m product.” These linguistic turns can be ignored, or regarded as a curiosity, but I see them as guideposts. The way humans talk about who they are and what they do will tell you a great deal about what they value and what they see their role as.

If you cared about being creative in communication 50 years ago, you were a Designer. Now, if you are interested in moving minds by creative effort in the most ubiquitous medium on the planet, you are in Product.

Fifteen years ago, I was a designer. Now, if I had to define what I do, it would be more product. What does that mean? Often, language changes are a useful barometer. Design conveys a sense of craft, a sense of dedication to best practices, and the intentional effort behind serving those who use the end state. Product conveys capital. It conveys an object to be sold. It conveys a unit to be moved, to generate upward momentum on a share price.

Designers are generally prompted by helpfulness; at the risk of being too self-congratulatory, the reason a certain type of human becomes a designer is the promise of solving problems and making things easier for your fellow human(it certainly isn’t the money). I fear that this trait is a big part of the drive to adopt this templated existence. We want to make the most good for the most people, and on its face, system designing seems to fit the bill. But it’s so short-sighted, and makes me fear for the long-term valuation of design. After the last template has been made… what then? The job stops being making and starts being caretaking the system, at best.

It’s entirely possible the type of creativity I practiced on the internet previous to 2014 was something else, and not ‘design’. But increasingly the type of design-by-metronome practice which follows closely the rise of product-oriented VC-backed start-ups and large-scale digital transformation doesn’t feel like something a human has to do. It feels like something that a product-oriented AI could do. And that’s intentional.

After Ford established his factory, very quickly, other large enterprise automakers fell into line. As evidenced by the chart above, just as so many new ideas were born in a golden age of innovation, so many were subsequently cast aside when the dominant model was adopted. The few remaining titans were able to reap the rewards of the model that was agreed upon. Would another model have been even more successful? We’ll never know. The pattern was set. The roads were laid. The highways were built. Climate change was baked in. At no point in time, was it asked, “Should we do this?” There was money to be made.

My great fear is that we are at a similar moment. One of the worst things about being a human is that we are useful for such a fairly short amount of time. If you are lucky, you get a solid forty years of contribution. As a result, it’s hard to see yourself within the current historical context.

At some moments, being innovative is useful and profitable. At other moments, it’s viewed as foolish. Over the past year, I’ve come to understand that I came up in the flare phase, and we are now in the focus phase of digital creation. At first, I was baffled and angry, but soon I came to realize that the sweep of history had caught me up in its tide. From here on out, it will be about scaling, about fundamentals of turnkey solutions, about velocity of deployment and serving as many humans as possible with the solutions we have come up with. Are they the right ones? Are these patterns dark? Are these choices intentional? It doesn’t matter. It’s time to ship ship ship.

I’m not alone. The cohort that came up with me is not used to this stance. We were told that we were on the precipice of a new era, and anything was possible. It was time to change the world. This dream is now very clearly dead. And now that rhetoric has been shelved, what does this mean, tactically, for working designers? From my perspective, four things:

- Digital design will eventually become akin to a manufacturing job. This is not on its face a bad thing (we’ll need replacement IRL manufacturing jobs), as long as the wages stay high enough to sustain a middle class lifestyle. A lower bar for entry, as well as the continuing deep need for the digital transformation of everything, will keep the role demand high. However, it won’t be the hifalutin “innovation” stance of the previous era.

- Downward pressure on wages. The brief era of design having a moment in the sun is over. There will be a continuing devaluation of design teams and the work they bring, because the solves have presumably been made and agreed upon. In addition, it’s nearly inevitable that a product-oriented generative AI that pulls from an established library of patterns will turn design from innovation into pattern library and assembly management.

- Dark Patterns are probably here to stay. Unless things radically change, everything from pop up ads to scam funnels are baked into the system.

- Customized bespoke digital experiences will become a luxury item. The industry need for innovative digital design won’t go away, just winnow. There will be some actors with enough money to create truly amazing experiences that draw users in and generate buzz. But the competition to create those experiences will be fierce, and the amount of individuals and agencies who can capture that work will be small.

I’m torn as to whether I’m disappointed in the change I foresee, as I don’t think that’s a useful construct. I just think it is, and as temporal humans that are forced to navigate an ever changing landscape, our task is to paddle the waters and not fall off the boat. My hope is that, as the industry changes to suit the future needs, we don’t abandon many of the principles that got us here in the first place.

Small jobs, small dreams was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply