How AI, plagiarism, and burnout are challenging what we consider fair in the business of design.

- The 2008 Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike reshaped media labor, and tech may be on the verge of a similar reckoning.

- Bungie’s Marathon plagiarism scandal exposed systemic failures in attribution and accountability.

- Creative workers are more essential than ever, but often erased from the final product, especially when that work is generated using AI.

- Fairness in creative work isn’t just contractual — it’s collective, perceptual, and fragile. Most of all, it requires honesty.

Beneath the deluge of model releases and AI product innovations in the spring of 2025 flows a quiet current of consolidation, the top names in tech and design swallowing each other whole to cut the form of the next creative economy. “Jonathan Ive Joins Forces with OpenAI”-type articles lead the tech news cycle, the watery black-and-white photo of the two men’s soft smiles peaked the fold on most tech news sites for days. More subtly, legacy giants like Ogilvy are building bespoke AI pipelines¹ that will soon pump out the hyper-targeted ad creatives destined to become the norm². And adrift in this news, I’ve found myself obsessed — not with a headline, but with the collapse of a video game reboot and the smell of burning oil on a summer day.

The Strikes

I stood across the street from a picket line in 2008. I was twenty-three and mostly invisible, working inside the Burbank lot but not quite in it, moderating comment threads for NBC.com. The WGA writer strike was at its high, so every day I watched the people I wanted to become trudge around near my office complex in a compelled protest until their guild-required hours were met and they were allowed to drive off to a home with the air conditioning and reliable plumbing I dreamt of. That day, Jay Leno had pulled up to support the writers, then as I gathered, the ridiculous car he drove there caught fire. I remember him calmly spraying a fire extinguisher, which he must have had at the ready, over the glowing hood while the striking writers looked on with total apathy.

2008 turned out to be the year that changed my life, though it didn’t feel like it at the time. While most of the entertainment industry was bleeding out — development deals evaporating, assistants getting laid off mid-email — NBC.com was quietly expanding. I was working 39-hour weeks — one hour short of what you’d need to get health insurance — out of a windowless cubicle, doing whatever passed for digital content moderation back then, which meant combing through message boards, formatting recaps, and at one point, verifying whether message board posts about one of the new American Gladiators doing gay porn before donning a whole different, prime time appropriate cock sock were true. It was absurd work, but it was work. And while people I went to college with were sending out résumés into the void or pouring drinks in Silver Lake, I had a badge, a job title, and a seat on the inside. Sort of.

One of the designers in my cubicle collective — a soft-spoken guy named George Yoon — once told me about how, on Court TV, a senior manager used to oversee the freelance contractors from an actual raised platform deck, like a lifeguard at a public pool. “But he was a really cool guy,” George added. “It was a good gig.” At the time, it didn’t seem strange. What struck me more was how normal it had all started to feel. I’d graduated with a screenwriting degree six months earlier, imagining I was destined for writers’ rooms and late-night brainstorming sessions, but the strange truth was that tech — at least in those early NBC.com days — felt much closer to the zany office culture I’d daydreamed about.

My sympathy for the TV writers wore thin pretty quickly. Sure, they were fighting for their future, but I was making twelve dollars an hour moderating message boards full of My Name Is Earl flame wars and making sure dweebs weren’t using javascript to hack our “The Office”-themed in-browser flash game in a way anyone could notice. Meanwhile, some of these guys on the picketline were pulling in doctor money to make sure every page of a Two and a Half Men script hit its quota of two dick jokes and a fart. It was hard to feel too heartbroken for a club I’d never be invited into.

As the strike dragged to a close, rumors of a deal were everywhere, and when my floor got the all-hands mandatory meeting invite with a half-hour notice, we knew it was here. That meeting was the first time I got a real look behind the curtain — my first experience watching a lawyer address a room full of tech people. The stage was aggressively stale: a fluorescent-lit boardroom with a speakerphone in the middle, but the actors were remarkable: techies packed the room beyond standing room only, the svelte middle managers in their late forties, wearing collared shirts and face moisturizer, trying to stay dignified as they angled their chests to let the girth of fanny-packed QA engineers squeeze past them. A room with a milieu of roles and potpourri of odors that would define the next decade of how entertainment industry types got paid. This seemed like the most important meeting I’d ever witness — and to this day, it is.

Everyone who paid rent by making film and television — whatever side of the camera or desk they were on — in 2008 was in a meeting just like this one. We were informed a deal was struck, and it really came down to this: for the first time ever, union members would get paid residuals on streams, but that residual would be infinitesimal. So small the magnification needed to perceive it on the number line crossed the barrier from the Newtonian to the Quantum, where attribution fractured, value scattered, and certainty vanished.

That’s the deal we have today: if someone makes money from a stream showing media you help create, you should get paid — but how much and how often is a quagmire. Drawing the line between what’s fair and what’s exploitative often comes down to whether enough people agree something is in the spirit of the agreement, not just the letter.

The producers and guild executives were right: streaming was the future — just not in the gradual, manageable way anyone had hoped. It came faster, hit harder, and rewrote the rules more brutally than most of them could have imagined. And that shift needed infrastructure. Streaming didn’t just need content; it needed interfaces, flows, buttons — digital products designed from scratch. Less than four years after I was auditing the chastity of American Gladiators for poverty wages, I was wireframing the very platforms that would drip out fractional pennies to their descendants for generations.

The 2008 agreement had worked — technically. The real profits of streaming flowed to the platforms, the tools, the algorithms. But the creators — the people who once knew how to get millions to tune in at 8 p.m. sharp — turned out to be the same people who knew how to get someone to press play on a thumbnail. They got paid. What they got paid was, legally speaking, appropriate. Fairness was more elusive. Debates about what was fair always seemed to settle once enough people agreed it felt fair. And that — feels fair — was the invisible force that lifted micro-fractions of a cent per stream from quantum uncertainty into the Newtonian realm of dollars and cents, printed cleanly on a residual check.

I remember visiting the Paramount lot for the first time years later, genuinely excited to walk into the “Gene Roddenberry” conference room — expecting something futuristic, almost sacred. Instead, it was beat up and strangely beige, like a mid-tier airport lounge with a plaque. The executives I met with, though, were warm, grounded, and deeply human. They listened. They asked smart questions. One of them was visibly excited about taking their kids to a family-only screening of Wonder Park that weekend. It was the opposite of everything I’d been told to expect back when I was a grunt at NBC — when “executive” meant someone whose job seemed to involve being chauffeured between panic and lunch.

There’s a popular fantasy that everyone in Big Tech or entertainment is rich. They’re not.

Most people I’ve worked with are just trying to make rent, keep their benefits, and maybe hold onto their job through the next reorg. But there’s a tiny subset — maybe a few hundred people across all of FAANG who are. You don’t encounter them often, but when you do, it’s disorienting. I’ve found myself somehow a part of conversations, with thoroughly lovely men, about the pros and cons of racing slicks on one’s track car, or how fulfilling it is to watch one’s child succeed at their high school’s helicopter piloting instruction. Most of the time, though, the entertainment and tech industries aren’t made of people like that. They’re made of people trying to get by — people who still comparison-shop health insurance plans and split dessert on business trips.

I was around for the 2008 writers’ strike, but only just — tucked away inside NBC’s digital arm, still figuring out what a CMS was, watching the picket lines from a distance. I wasn’t one of them. I didn’t know anyone with a WGA card. The strike felt abstract — loud, yes, but not personal.

The 2022–23 strike was different. I was still working in entertainment tech, but now I lived in the fashionable Silverlake neighborhood where a lot of the people who made television lived too. My kid went to school with their kids. Suddenly the strike wasn’t a line of signs at a studio gate — it was a marriage hanging on by a thread, the dad who didn’t know if his writers’ room would ever reopen, the mom scrounging for college essay editing gigs just to cover groceries. These weren’t people striking over abstract residual formulas. They were trying to figure out how to hold onto their healthcare, their homes, their reliable plumbing.

The 2008 agreement had technically been followed, but that agreement didn’t feel right in the stream-driven, post-pandemic entertainment boom. The numbers were there, but the sense of fairness wasn’t anymore. Eventually, an inflection point was hit — and it was pencils down. Because creative work, especially the kind built by hundreds of people and leveraged into billions of dollars, doesn’t run on compliance alone. It doesn’t run on clock-ins or clean deliverables. When your work is intellectual property — subjective, collaborative, and ever-evolving — what matters more than policy is perception. Fairness isn’t a fixed number. It’s a feeling. And the real work of organized labor isn’t just negotiating legal frameworks — it’s generating enough shared understanding of what feels fair that people are willing to keep building together. That’s what sustains creative economies: not rules, but consensus that holds.

History Envy

In entertainment, there’s at least a structure — flawed, yes, but familiar — stretching back to the days when Thomas Edison’s enforcers chased filmmakers out of New Jersey. Writers understand the role of a showrunner. Art directors know how to collaborate with DPs. There are guilds, workflows, hierarchies. People know, more or less, where they stand — what they owe the community, and what the community owes them.

Even when the rules get murky, there’s still a shared understanding. A kind of cultural muscle memory. People agree to treat certain numbers as meaningful: that Nielsen ratings matter, that a royalty check represents something real. It’s not law so much as ritual.

In tech, there’s no equivalent spellbook. No inherited structure. No union heads to pressure into a deal. Credit might live on a forgotten slide deck — if anyone saved it. And when your design ends up embedded in a feature, that gets scraped into a dataset, that trains a model, that powers a campaign, that wins an award — there’s no mechanism for redress. That’s just how it goes. For now.

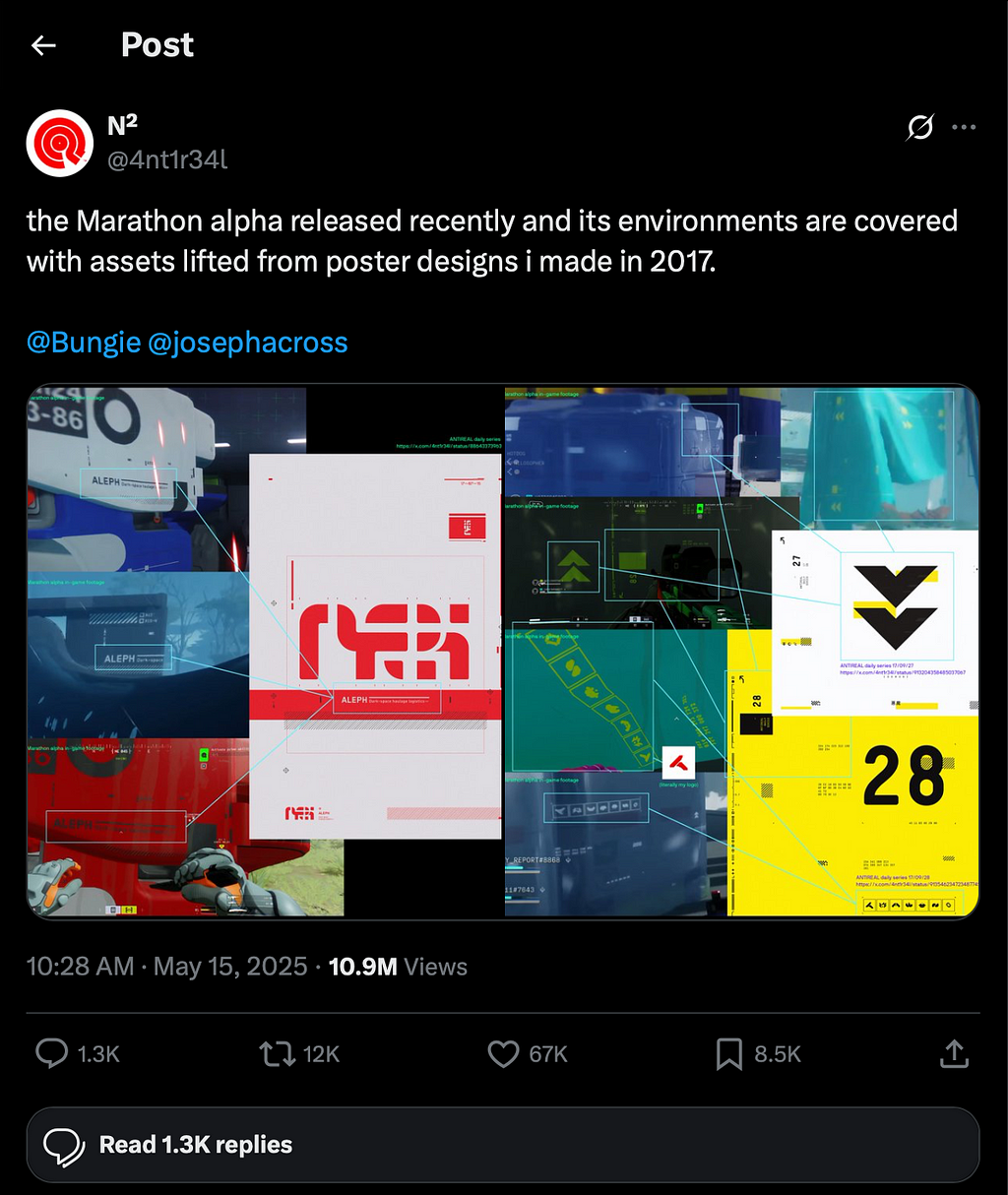

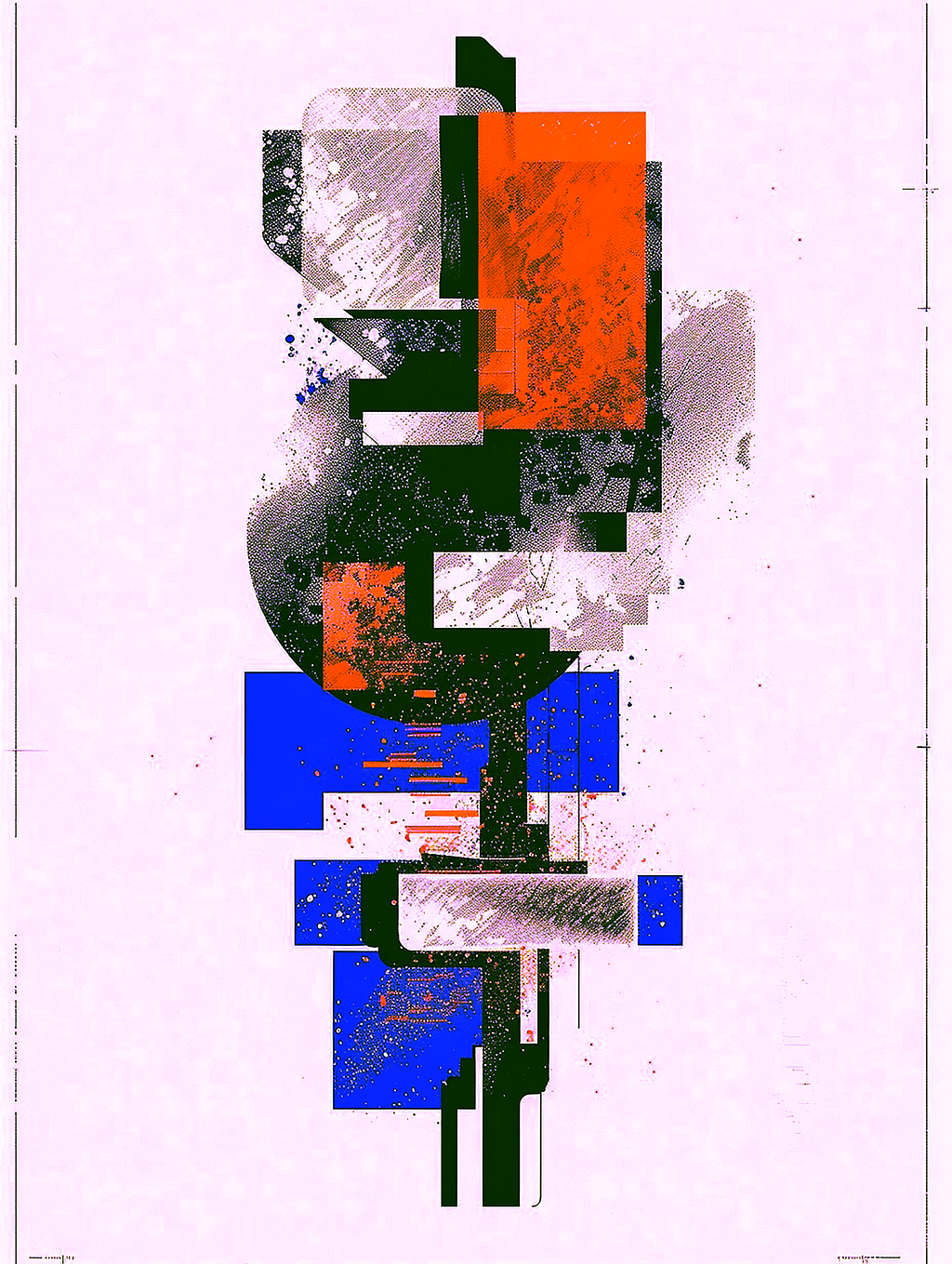

The industry I work in now — digital product design — feels like it’s teetering on the edge of its own 2008 WGA moment. Only ours might be more severe. The Marathon plagiarism scandal — where Bungie incorporated artwork by independent artist Fern Hook (ANTIREAL) into its reboot of the classic sci-fi shooter — didn’t just raise eyebrows. It felt like a breaking point. Hook posted direct visual comparisons showing that her 2017 poster designs were lifted almost pixel for pixel: decals, stylized text, even her logo — hastily blurred — appeared in promotional Marathon assets³. Bungie publicly acknowledged the issue, blaming it on a former designer who had inserted Hook’s work into a texture sheet back in 2020. That texture made it into the final visuals — undetected by the team for years⁴.

Joseph Cross, one of the game’s art directors, issued a personal apology in a live-streamed presentation, admitting there was “absolutely no excuse” for what happened⁵. Bungie committed to scrubbing all plagiarized material and delaying upcoming promotional releases until a full audit was completed⁶.

What made this moment so revealing wasn’t just the theft — it was the aftermath. Who got blamed. Who got protected. Who disappeared from the narrative. There were no union heads or formal grievance channels — just a flurry of social media outrage on one side and carefully worded corporate statements on the other. Despite Bungie and Hermana Creatives’ (the large creative agency hired by Bungie) attempt to shift blame onto a now-departed subcontractor — a familiar, overstretched freelancer profile if ever there was one — the public’s frustration wasn’t aimed at that individual. It was directed at the system itself: one that continually erases the hundreds of hands behind the kaleidoscopically intricate, oil-slick billion-dollar properties we call AAA games.

The Machine Forgets Who Fed It

The demand for individual creative contributors — those whose creative instincts shape culture, sell hardware, and define billion-dollar brands — is about to surge, driven by generative AI’s paradoxical and growing hunger for original, deeply human creative work to train on.

Let me take you to the rooms that feed the models that fed or are feeding this next wave of advertising. Picture it: a windowless office tucked behind a loading dock, fluorescent lights buzzing overhead. A stylus taps a screen. A mouse hand scrolls. A retoucher leans in too close to a smudged monitor. The cursor flickers. The work is numbing. Logo lockups, pitch decks, styleframes for title sequences that never get made. It pays a little more than pouring lattes. No one planned to end up doing this, but here they are — folded into the production pipeline. Whether the job’s for a streaming series, a sports brand, or a crypto startup no one really believes in, the work gets done. It’s signed away with NDAs, buried under version numbers, and backed up on servers.

Then — years later, on another continent entirely — another machine wakes up. The data center isn’t a room you can walk into. It’s a warehouse-sized hive somewhere in Iowa, or Taiwan, or an abandoned submarine hangar in Finland. A GPU hums as it begins to train. It ingests decades of work, millions of files from a thousand artists who we will never know. No names. No links. Just the cumulative residue of commercial imagination: LUTs, rigged models, casting selects, graphic passes, flattened PSDs, motion studies, animatics. All stripped, diced, and emulsified into vectors the machine needs to chew.

If the data isn’t fresh — if it contains too much work from other AI — it begins to spoil. The vectors collapse inward. Patterns fray. Noise begets noise. It is called model collapse. Models driving a machine so hungry, it eats its own tail. Then its teeth. Then its stomach. The machine, trained on the rancid slurry, generates copies stacked on copies stacked on guesses. Skin maps to skin mapped to shimmer mapped to fog. It generates horrors. Eyelashes that blink in the wrong direction. Fingers growing from palms. And the ad the model is paid to generate is nothing but a fever dream set to the sound of breathing.

The pure mixture that keeps the nightmares at bay requires the forgotten labor of people who worked in rooms with bad lighting and cheap office chairs. People who made things that looked like nothing, until they looked like everything. What is the value of the artist who feeds machines not yet invented, whose work is crushed into unrecognizable powder and used to power worlds years in the future?

What is fairness for them?

Honesty First

As I burned down the first draft of this essay — researching the strikes, combing my memory for every detail — what stood out to me, embarrassingly, was how little I thought back then about what was fair. Whether there was such a thing as a fair system. Whether fairness, even if beautifully constructed, could ever be practically true. No one asked me for my thoughts at the time. But now, years later, mid-career, in an industry that feels like it’s tilting underfoot, I wish I’d thought more seriously about it. I feel unprepared to give answers. But I feel I must try.

For all the ambiguity around fairness — legal, cultural, emotional — the one quality I keep returning to is honesty. Not transparency, not attribution, but something more elemental: the refusal to pretend. And when I try to picture that idea, I see Jeff Koons’s Rabbit sculpture. Chrome and enormous, it stands polished to the point of erasure — so smooth it seems less sculpted than conjured. Its surface reflects everything around it: gallery walls, skylights, spectators. And when you step close, it reflects you too — only bent, stretched, made strange.

Rabbit was the most expensive sculpture by a living artist ever sold at auction. And there are three of them. Koons didn’t cast them, didn’t weld or polish the steel. It was his idea, and that was enough. People argue about the value of that, and they should. But Koons never lied about his role. He said, this is what it is, this is what I did. In a landscape where authorship blurs and fairness dissolves into press releases and settlements, that kind of honesty — even if it’s hollow — is a shape I recognize. He doesn’t pretend it’s something else. And maybe, for now, that’s the clearest form of fairness I can name.

Footnotes

- Capitol Communicator, “Ogilvy cuts workforce as it moves to modernize its business model” (June 2025)

- Ogily.com, “Ogilvy Athens, The Impact of AI on Marketing: From Algorithms to Artistry (May 2023)

- Fern Hook’s original comparisons and allegations were documented across her social media, and amplified by fan communities. See Famiboards (May 2025) for visual side-by-side analysis.

- Windows Central, “Bungie responds to Marathon art theft controversy, admitting it stole assets and blaming a former developer: “We are conducting a thorough review” (May 2025)

- The Game Post, “Marathon Art Director Joseph Cross Issues “Personal Apology” for Plagiarized Art: “There’s Absolutely No Excuse For This Oversight” Art director Joseph Cross issued a personal apology during the PlayMA livestream. (May 2025)

- Games Radar, “Bungie runs an hour-long Marathon “PlayMA” with zero gameplay footage while scrubbing the art for plagiarism as the game’s art director offers a “personal apology” to the artist whose work was lifted” (May 2025)

Other Sources

Anthony Ha, “OpenAI pulls promotional materials around Jony Ive deal due to court order”, TechCrunch, June 22, 2025

Laurel Wamsley, “Jeff Koons’ ‘Rabbit’ Fetches $91 Million, Auction Record For Work By A Living Artist”, NPR, May 16, 2019

Fairness isn’t a metric: what creatives in tech should learn from the WGA strikes was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply