Raw, real, human, and ’imperfect’ stories impact design, business, and life in a world obsessed with being polished.

As augmented reality will be more integrated into daily life, designers must rethink interactions from a third-person perspective to preserve social harmony in shared spaces.

This year, AR is making big promises. With Vision Pro, Snap’s Spectacles, and the very new Meta’s Orion, it seems like we’re finally touching the edge of AR glasses becoming persuasive personal devices that may replace your smartphone (though we’re still years away).

But here’s the thing: while the technology seems ready, our design mindset isn’t keeping up. AR interactions today are self-centered, ignoring the social and public spaces we share.

Every time you put on AR glasses or hold up your phone to “catch” something invisible, you’re not just interacting with the digital world — you’re broadcasting your actions into the real one. What happens when these private, personal interactions start to disturb the people around you? How other people around you will react to it? Avoidance or discomfort?

This isn’t just about technology; it’s about social etiquette. And AR will and is creating new conflicts in public spaces that never existed before. And it’s time to ask: How will such pervasive AR device reshape the social interaction of our lives? How should we guide the design for it?

AR as a self-centered disruptor

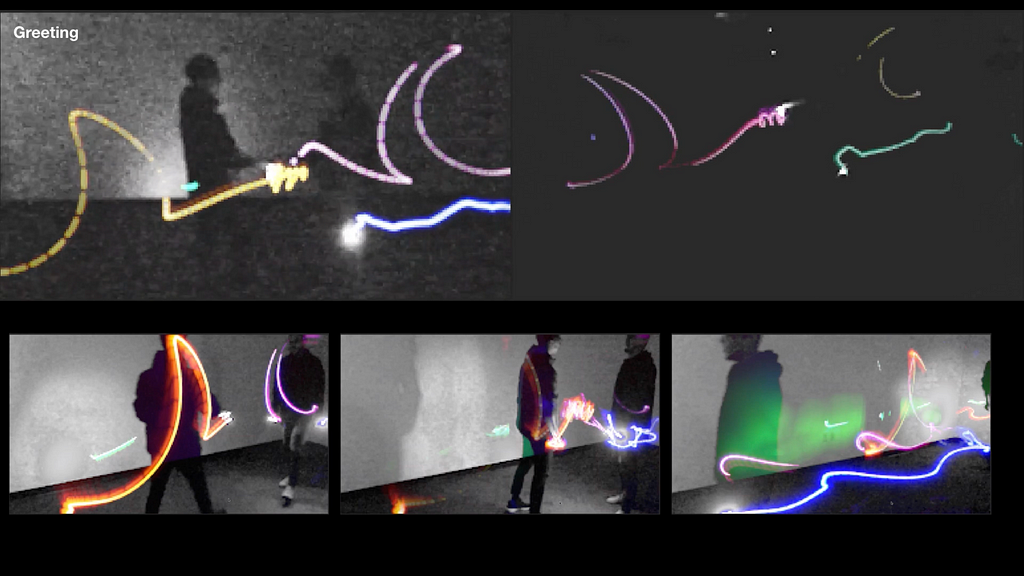

Let’s look at how people use AR today. Picture this: someone’s standing in a park, holding up a phone, using it to catch something on their screen. Or picture someone wearing AR glasses, waving their hand to interact with a digital object that no one else can see. It’s like they’re cut off from the rest of the world, trapped in their own little digital bubble. The interactions are private, but the gestures are public. And this disconnection creates awkward, sometimes even disruptive, situations.

Take Pokémon Go, for example. When it first launched, people swarmed public spaces to catch virtual creatures. Sounds fun, right? But if you were in Central Park during that craze, you might have heard the chaos in central park in 2016: people walking into each other, blocking paths, and generally behaving in ways that made no sense to anyone outside the game.

Suddenly, AR had turned into a social disruptor. What will happen if ten people(I was like to say hundred but ten is enough for imaging) throwing Poke Balls or chasing and playing with Pikachu and Eevee with actual AR glasses? The chaos could be even worse. And the people around you could step in your way for not knowing anything.

That’s the key issue here.

““We disturb others when we use AR — and they unknowingly disturb us too.””

As AR becomes more integrated into our daily lives, these disturbances will only become more common.

Body movements break the peace

Here’s where things get complicated: AR doesn’t just exist on a screen; it takes up physical space and influences body movements.

Think about it. When you take a photo with your smartphone, the people around you get it — they understand what you’re doing because it’s a shared social behavior. They recognize that you’re using the space in front of you for a moment, and they either avoid it or they might just ignore it — but they understand it, the smartphone and your gesture act as social cue.

But AR will always take up some public space to display the content, virtual objects. Your body movements can change by the presence of the virtual objects in a similar way they would be if the object is real. You might be swiping through menus or manipulating invisible objects. To others, it looks strange. They have no way of interpreting your actions because there are no established social cues around AR interactions. These movements can feel alien, even disruptive.

Some thoughts from outsider can be:

- “Are the waving hand is say hi to me or he is swiping the virtual screen?”

- “He is throwing something in the air, what is up there? It’s a hint for me?”

This isn’t the user’s fault. It’s an issue caused by AR systems. They take up space for individual interactions without any communication or consideration for others. The body movements prompted by AR are the only signals others can try to interpret, and it’s hard to tell if an aggressive gesture means something important or if a stretched arm implies someone might use that area next.

This uncertainty break the social peace.

Body movements shape social etiquette

The space in public is a limited resource. We use architecture and landscape to reach a “common agreement” on how we share public space collectively. On an interpersonal scale, we use body movement to share public space improvisationally — this becomes social etiquette. And we keep shifting our position and movements based on each other’s relationship, personality or even just mood.

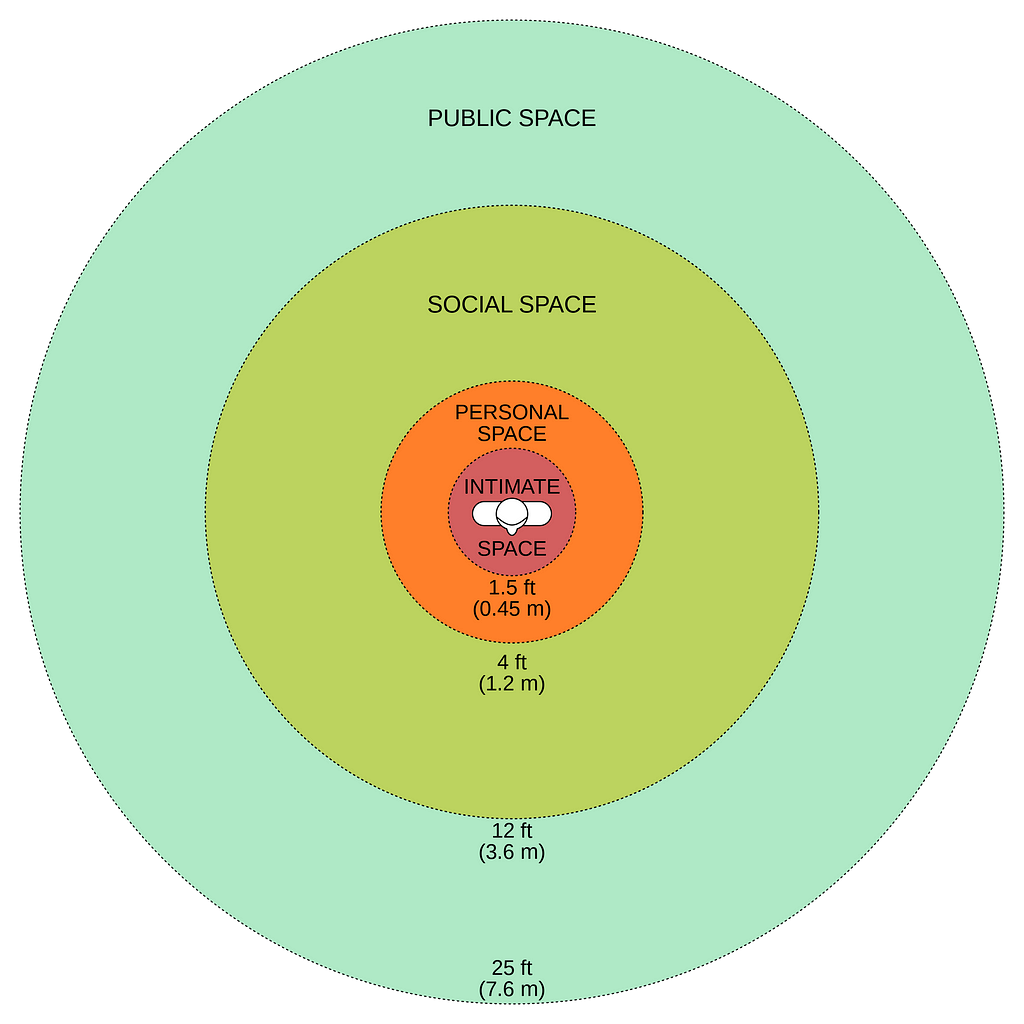

The Proxemics and Kinesics studies show interpersonal distances and interpretation of body communication of people play a key role in non-verbal communication.

To explain it, the neuropsychology describes those space in terms of the kinds of “nearness” to an individual body.

- Extrapersonal space: space out of reach

- Peripersonal space: space around arm’s length

- Pericutaneous space: space just outside the body

It demonstrates spatial variation in the ability to reach by people’s arm. People’s reactions vary when these zones are intruded upon, reflecting a temporary “authority” over their personal space in public. We naturally recognize and respect this authority.

And from Kinematics explanation, studies show that the direction of the head and the intention to move are key indicators in finding comfort zones in public spaces. Interestingly, the study uses the people’s moving intention and vehicles moving intention to see how they decide who has the right to proceed. A great example of maintain some kind of social etiquette via non-verbal communication.

Many body movements create patterns that we recognize and navigate. The way you move in space signals your intent, allowing others to react appropriately. The speed and range you stretch your arm signals the active area under your temporary control. Your presence and existence in a location, allowing others to recognize your long term needs of that place.

And we negotiate through it. Negotiation means we use body movement to deliver a message of what and how we want to use the space and we also use it to react to or respect those message. A bunch of back and forth to reach agreement:

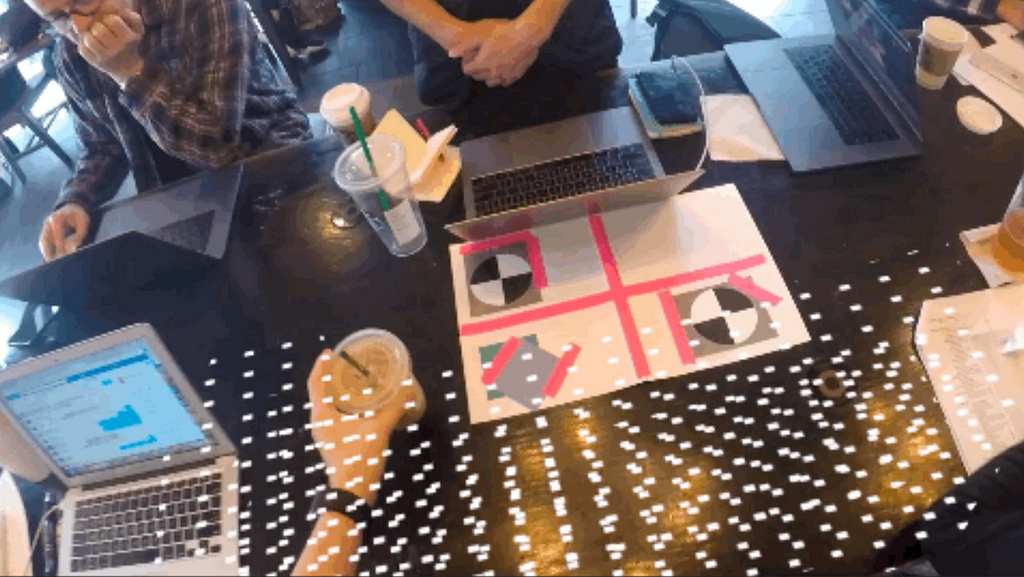

In a crowded coffee shops or metro, people use their arm moving area to push back and make the boundary of you sit and work. Others will lean back and tighten their arms to react to your movements.

In a classroom you leave your clothes at chair you sit for whole day for reading and leave for a getting coffee, people know you still own that space and they will use the space around it and keep it for you for a while.

Designing body movement for social etiquette in AR

Tech companies spent many resources on live scanning the physical world with SLAM for AR system. Because the physical world is the natural restriction for displaying augmented content. So does the social etiquette, it creates natural limitations for designing user’s interactions in AR.

Here’s where it gets interesting for us designers. We’re not just creating interfaces anymore — we’re shaping how people interact with the world and each other. AR needs to be designed with both the user and bystanders in mind. How can we design experiences that are immersive for the user but not disruptive for everyone else? Here are some approaches we can probably try:

Use minimum body movements

Problem can always be solved If we can use our brainwaves to control everything. The idea of minimal effort on interaction is always a good approach, it basically creates a superpower-like feeling without being obvious to others.

There are many technologies created for controlling the AR in a minimum way. The Google Silo, the eye tracking and hand recognition on Oculus and Vision Pro, even the wristband from Meta Orion. They using gazing, using fingers movement, or use your palm as a pad to pretend to be some “screens”. clearly, we see those efforts to limit the impact while using AR system.

But I have admitted, this isn’t the really the exciting part when I looking into future AR. It was always something like the HYPER REALITY that you actually can using hand to grab the virtual objects and actually play with it. So the minimum body movement is a necessary approach for people to enjoy AR easier and longer but still not enough.

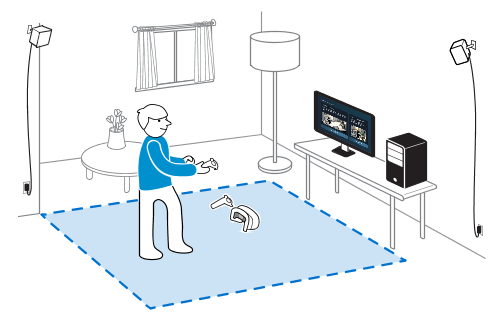

Allow users to define space before using

Another good idea is to have user draw the boundary for themselves. It’s a proven method and use a lot in VR device. People draw a safe zone for enjoying VR content. We can do the same thing in AR.

The challenge is as we assume AR device the glasses become next smartphone, it‘s not pratical to do this every time we use them. I might draw a boundary if I’m playing an immersive, heavily interactive game to ensure that people around me understand my strange behavior. But for casual interactions, like throw a virtual poke ball to catch a Pikachu? Huh, I’m not so sure.

AR interactions can vary widely and evolving over time. There should be a smart way to having this “define” process. Finding a consistent rule for what is allowed within the zone is difficult because the context can always change. A more flexible approach is better than a fixed boundary.

React to body movements like in the physical world

By synthesize many common situations in daily life to find rules of social etiquette. We can just use it to design how the user’s movement should be in AR. I sum it up in three categories:

- The type of the environment

- The existing body movements

- The ongoing body movements attempts

The environment type provides a baseline of overall body movements. The AR content should design to meet these natural rules.

Similar idea has been brought up in virutal reality(VR) design for a long time. The only difference is that the environmental constraints they focus on are the virtual social constraints within the VR world, whereas in AR, the environmental constraints we deal with are the real, tangible social environment.

a space type creates a social expectation

Just as we instinctively know how to behave in different settings, AR interactions should follow similar guidelines. For example:

- Don’t stretch your arms or legs in a crowded café

- Be gentle with your movement in a quiet museum

- Follow the moving direction of the crowd

We can expect how our behavior will affect other people and adapt ourselves into it. All of these observation and evaluation happens instantly, just like how we understand the rule of physical. The environment type together with physical world set the ground of how AR content should be initialized.

The existing body movements provide immediate cues about how space is being used, helping us reach a quick, unspoken agreement. Some behaviors are kind of in a blurry situation, and that’s where we need to figure out. For example:

Sit in café to write my book, I intentionally lean toward the table and spread my arm to take more space and be more focus,. Others recognize this and respect my area.

In a library, if I leave my belongings on a chair to stretch or get a coffee, people understand that I’ll likely return, so they leave the seat for me.

As I walking quickly through a square, others adjust their paths to avoid my way, and I do the same for them.

Different parts of body and the way they move has different meaning to others:

Limb movements to claim space. Limb movements including hand gestures show the temporary space that we can reach and under control. The stretch and the speed of limb movement affect the size of this temporary space. For AR, content could adjust accordingly, allowing remote or direct control based on how limbs stretch. Hand and arm as main input for most of current AR device, there are many AR design guidelines and discussions have covered this part, more about hand gesture as interface and the potential social implication.

Trunk dynamic to indicate space. Trunk dynamic, for example, how we lean and walk toward, show the space that we plan to use. For AR, content with lower interactivity like notification can respond to this movement subtly, offering brief interactions without being disruptive.

Body presence to occupy space. Simply being in a space signals temporary ownership. The longer we stay, the stronger the space authority we get. For AR, content with higher interactivity should stay in this space. The content can increase their visibility and interactivity to take full advantage of this occupation.

By continuously scanning the environment for existing body movements, AR systems can provide a clear starting point for displaying content.

The ongoing body movements are where social negotiation takes place and social etiquette exists. These gestures often signal intent — whether testing boundaries or trying to establish control over space. For example:

If someone lies down on a bench in a busy park, it’s a subtle challenge to others: Am I comfortable staying here? Will others accept this? The outcome depends on the personalities of those involved.

If I’m reading a book in the center of a lawn and a group starts playing frisbee nearby, their movements might eventually drive me away, unless I assert my desire to stay by holding my ground.

AR interactions should be designed to recognize these negotiations. When introducing new interactions, AR systems can present them briefly and subtly, allowing users to signal their intent and negotiate space just as they would in the real world. Scanning the movements of everyone nearby helps adjust the content dynamically.

Ultimately, design from a third person point of view

Just as we respect the laws of physics when designing AR content with realistic occlusion and bounce effects, we should also respect social etiquette. AR interactions must align with the norms of real-world communication.

Six years ago, I wrote a brief design guideline on how we should design AR therefore peoples body movement would be nature and appropriate. Even now, with the Meta Orion and Vision Pro, we still see a self-centered design approach. Efforts like wrist control is good progresss, but it’s not enough.

An enjoyable and courteous even a fun AR future requires us to jump out from the long-existing user’s perspective and adopt a third-person point of view. We’re not just designing interfaces anymore. We’re designing the future of human interaction.

Reference:

- Previc, F.H. (1998). “The neuropsychology of 3D space”. Psychol. Bull. 124 (2): 123–164. doi:10.1037/0033–2909.124.2.123. PMID 9747184.

- Camara, F and Fox, C. (2021). “Space invaders: Pedestrian proxemic utility functions and trust zones for autonomous vehicle interactions”. International Journal of Social Robotics. 13 (8): 1929–1949. doi:10.1007/s12369–020–00717-x. S2CID 230640683.

- Camara, F and Fox, C. (2023). “A kinematic model generates non-circular human proxemics zones”. Advanced Robotics. 37 (24): 1566–1575. doi:10.1080/01691864.2023.2263062.

Body language in AR: Designing socially aware interactions was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply