If we are serious about social change and equity, we need to start centring the knowledge and decisions of those deeply impacted.

Who do we design for?

Most social impact designers and socially-minded agencies will tell you what they design for: a “better” future. But when it comes to who that better future is for, that is left up to interpretation.

Whether intentional or not, leaving out the ‘who’ in these mission statements creates a deceptive cover of good intentions. Where projects, no matter who the backers are, can be taken as long as there is a vague claim of positive change or impact.

As someone who has a neurodiversity-imposed sense of justice, I’ve come to find these claims of “better” as a “yellow” flag. I don’t dismiss the work. I’m just hesitant about how and who the work is really done for.

I believe that when we are designing for equity and justice, it is important we name and platform those deeply impacted by the systems we are tackling. Centring the deeply impacted in our work is crucial when we are designing in collective and community spaces. Even though it can be a lot easier said than done.

What does it mean to centre those deeply impacted?

To me, it just seems logical to have those with real lived/ing experience be part of the design team. Community members need to be the real decision-makers on projects that affect them.

Though as much as I believe this, I know that it’s not often an option. Be it lack of resources, time scarcity, and/or apprehension from management about sharing decision-making power- there are many situations where bringing a community member onto the design team isn’t the norm. (Though let’s get real, it should be necessary.)

And even when we’re all on the team, there is an innate power imbalance where funders and management have considerably more decision-making power. Often leading to communities feeling alienated throughout the process, and if their ideas are shot down, it can ultimately break their trust. Making it hard for designers, researchers, and policymakers to work with this community again in the future.

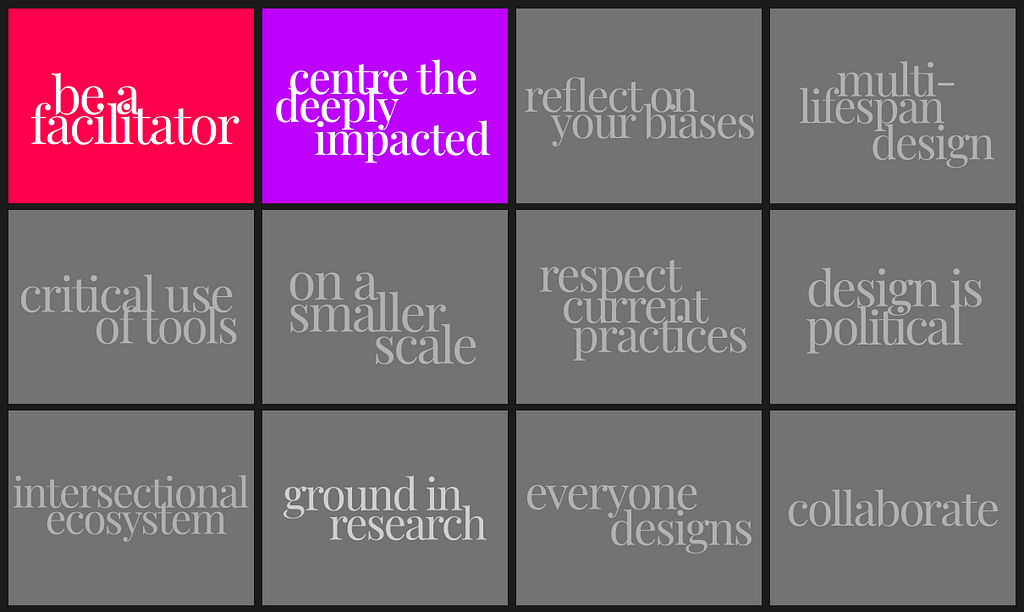

This seeming failure of logic is what inspired the second principle of Design for Collective Spaces: centre the deeply impacted(1). Much like the first principle is about shifting our view of designers from experts to facilitators, to “centre the deeply impacted” is about shifting which needs, wants, and knowledge are prioritized throughout the design process.

I have to admit, I find this particular principle difficult to clearly define. Likely as there is a lot of grey and subjectivity you’ll need to balance when implementing it. But for the sake of this article, I want to provide some working definitions and background. Hopefully, you get what I’m saying, try to apply it, remix it, and then let me know how it all works out!

Let’s start with the tricky task of defining “the deeply impacted”

When designers start a project, it is common practice to identify all the stakeholders in the ecosystem. This identification process can look like anything from creating personas, stakeholder maps, and/or behaviour analysis.

Honestly, it’s a lot of responsibility on designers to accurately define the deeply impacted. It’s not easy, especially as stakeholders change from each context. So I created the definition below to help make sense of it all:

The deeply impacted are the people/beings/environments where a system change could have a large impact on their life. They have lived/ing experience with the situation and often hold positions where they have little say and/or social power over how they are treated.

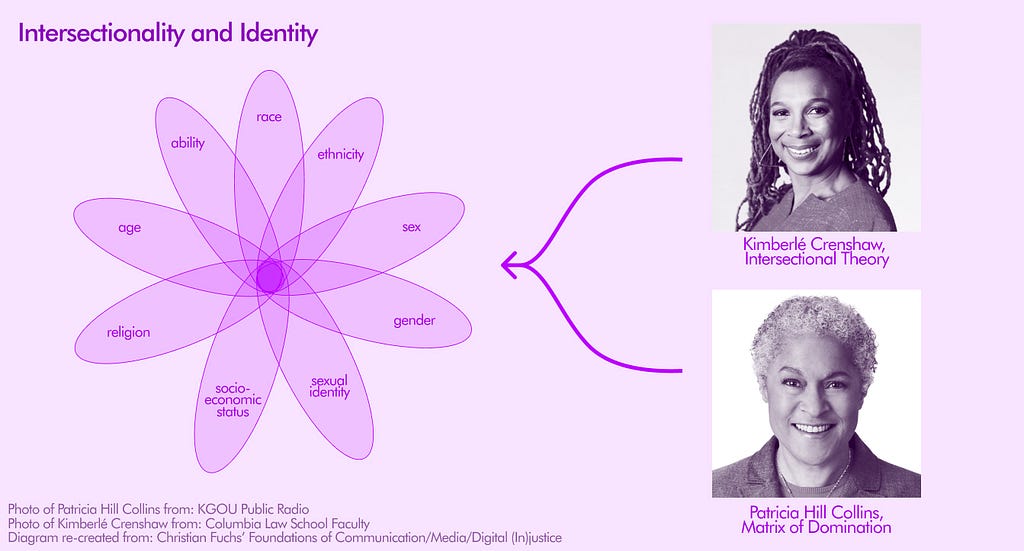

This definition asks designers to consider the social, economic, and historical aspects of the stakeholders we identify. It is inspired by legal scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s, intersectional theory and Black feminist scholar, Patricia Hill Collins’, matrix of domination. While each topic deserves their own article, the core message of both is that people hold multiple identities that privilege or disadvantage them in comparison to others.

As a whole, there are certain identities that society historically and currently marginalizes, oppresses, and committs acts of genocide against. Those who continue to face violence today are often people with Trans, Black, Indigenous, Arab, Queer, Disabled, and/or any other identities that fall outside of the ‘norms’ set by colonial European ruling classes an odd 500+ years ago. Sometimes this violence is innocuous, like poor closed captioning, while other times it is upfront, like the continued war crimes and starvation tactics used against civilians in Gaza.

And as socially-conscious designers, I believe it is our responsibility to be aware of how these identities play out in our work — doing our best to mitigate recreating similar acts of violence. No matter how small or unimaginably large…

Before we address “centring”, let’s discuss what it is not.

Truly heavy stuff aside, in my experience many social impact designers don’t struggle to identify who the deeply impacted are. The struggle comes in making sure those voices are reached, heard, and more importantly centred within the design process.

So what does it mean to centre the deeply impacted?

Before I get into the definition, I want to use this moment to address what you’re probably thinking it is: codesign. Which, according to Interaction Design Foundation, is “a collaborative approach where designers work together with non-designers”.

While I have no beef with codesign (I think it is great in theory), I find how it is normally applied underwhelming or sometimes downright problematic.

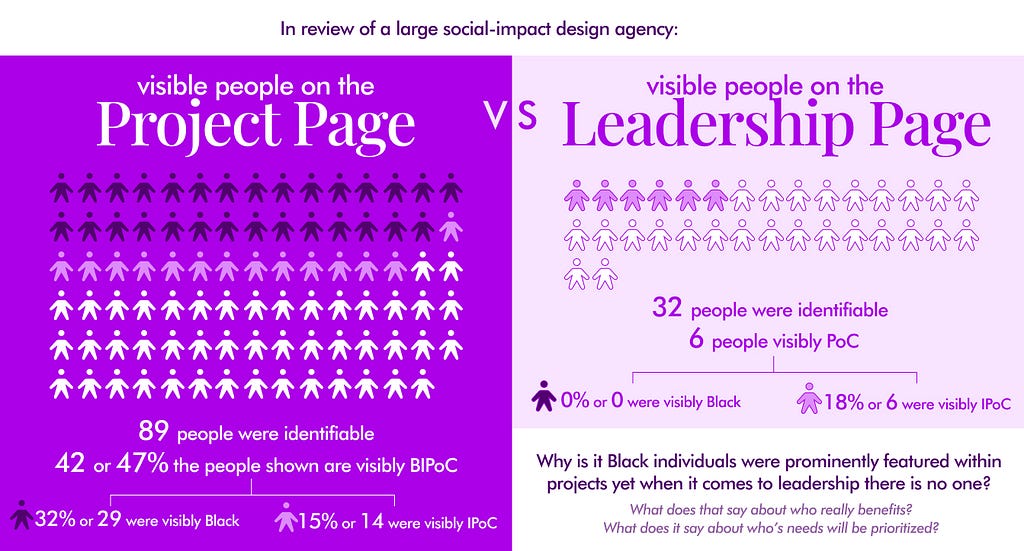

In my experience, the term gets thrown around quite liberally. Often used to describe something as small as a singular collaborative workshop or user testing, where the deeply impacted don’t really have decision-making power. Rather they are used as convenient ways to get the coveted design stories and photos that make a firm look more diverse than they actually are.

How codesign is currently applied feels very similar to greenwashing. All the stakeholders are now in the room, but there rarely are considerations to the unspoken power structures within it. How collaborative can a project be, if ultimately directors and managers have the power to veto ideas from their on-the-ground staff? Or have the power over who they let into this decision making process or not?

For example, years ago I was speaking with an agency about a project they were doing around public cognitive disability services. They had planned a months-long series of workshops to have people ideate, collaborate, and create new ways of providing care. All great and vital things that need to be done in the disability services industry. I was quite excited talking to them, as back in Canada, there are only a shrinking number of designers tackling this.

As a designer who lives with a disability and one who has worked in that industry, I asked a question I thought for sure this larger agency thought about:

“So, how are you making sure the ideas of folks with cognitive disabilities are being heard?”

And to that, with all their good intentions and great methodology, I was told that there would not be any people with cognitive disabilities attending any of the workshops. I was shocked.

In many ways, I understand that decision. There are serious considerations that need to be taken when including a marginalized population in the design process. Is your work trauma-informed? Will this harm more than help? It is very hard to get it right, that I get.

But in many ways, I don’t understand and along with many other decisions that are made under the umbrella of “co-design”. How can there ever be radical change if people with lived/ing experience aren’t even in the room? And when they are, they are not treated as experts in their own lives?

Codesign, just like “better”, is often used as a cover of good intentions. Talking to fellow social impact colleagues, it’s unfortunately a common experience for them to invest substantial resources in creating a collaborative solution, only to ultimately be shot down because funders or managers don’t like it.

It’s devastating and dangerous.

This ultimate veto power is innately harmful to what codesign truly could be. When a community spends time brainstorming, ideating, and creating only to be told that the people in power say “no”, it breaks their trust. In design and working with outsiders.

So then a project that initially was sold to a community as something that would “harness … the collective wisdom” and lead to more “inclusive, creative and user-centered outcomes”, just becomes another in a long line of other solutions that replicate harms that got them there in the first place.

So enter centring

How codesign is currently being utilized is not perfect. No one process can be. This includes centring the deeply impacted, but I believe it is a step in a more just direction.

When DCS first created this principle, it was a call to see people as the experts in their own lives. They may need time to find the words, the visuals, ways of expressing themselves — but no one knows their experience better than themselves.

So if we are doing projects about their lives, it is our job as practitioners to actually listen. To do our best not to re-marginalize or traumatize people within the design process. Making sure the process is centred around their needs. It will never be perfect or entirely safe, but we need to try.

We also saw this principle as a call for accessibility, equity, and inclusivity. It is no surprise that much of this world is inaccessible to marginalized groups. For example, the internet is largely inaccessible for people with disabilities and so is much of air travel.

Even though 1 in 4 people in Europe have some sort of disability, we are often left out of consideration within the design process or have our needs tacked on at the very end of it.

This experience is similar for many marginalized groups, our needs are deemed a necessary compromise to the “blue-sky”, “move-fast-break-things”, “simple 6 phase” design process that has long been taught to designers and that is ‘oh so comforting’ for funders.

This is why, in a protest to what is considered the norm, we ask for people to centre justice, equity, and accessibility in all their designs — even if the project isn’t particularly socially minded.

So with ALL of this in mind, the final definition of the second principle in DCS is:

Centre the deeply impacted: those who are most affected must be prioritized throughout the entire process. Be aware of power imbalances, and ensure that the most marginalized are not left out of solutions.

Like every design principle, of course this is a lot easier said than done. And since actually listening to people is a generally new practice (wild right?) best practices are ever-changing.

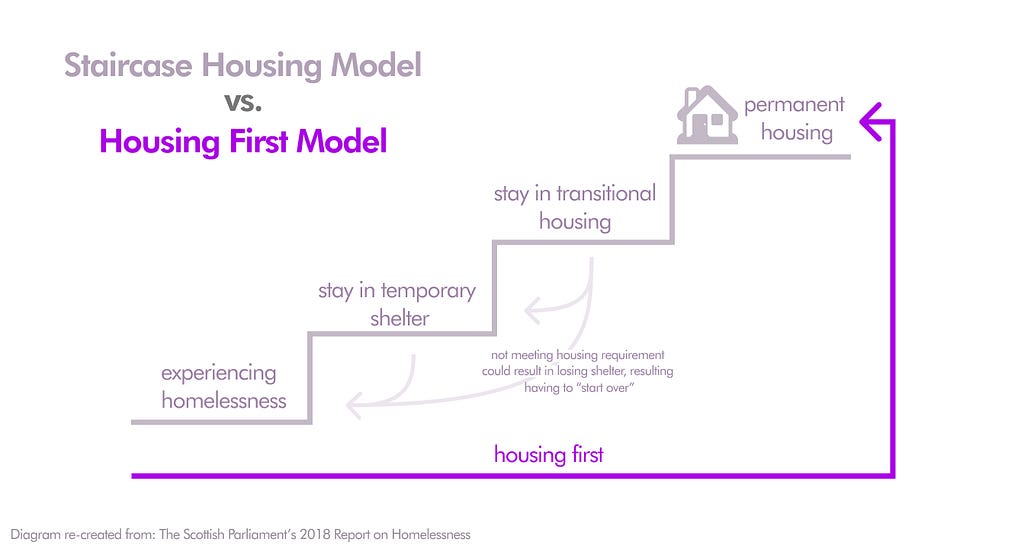

One well-known movement that I think can help us understand this principle are housing-first initiatives, specifically within Finland. This approach provides individuals experiencing homelessness with permanent housing first, before anything else. With it, Finland saw incidents of long-term homelessness decrease 68% from 2008 to 2022, according to the Y-Foundation (Y-Säätiö), the nation’s largest non-profit landlord.

While, like any policy, it has its issues, it is a far cry from the popular staircase approach, where housing is seen as something that needs to be earned. This approach acknowledges that there is no one specific way to live and a “home is not a privilege, it is a human right”.

Aside from this specific example, I know there are a lot of organizations that are coming to a similar realization about centring the deeply impacted within their processes. Specifically within design, I believe the Greater Good Studio in Chicago, the Department of Imaginary Affairs in Toronto, and the Design Justice Network are good organizations to pull inspiration from.

Tips and tools to centre the deeply impacted in your work.

Like I said before, there is no one way to do things. Each community you work with will have different needs, perspectives, and contrasting opinions. And as a designer, community worker, or activist there is a lot to navigate.

I first want to say that approaching marginalized communities who are outside of your own lived/ing experience can cause a lot of harm, despite best intentions. It is important to approach this work trauma-informed.

While I’m not going to get into the details of Trauma-Informed Design here, there are many great writers and designers who explore this approach. For example, kon syrokostas recently spent 20 weeks reflecting on the topic of Trauma-Informed Design from a personal perspective. AND there is Pause + Effect, who hold workshops on Decolonizing Trauma-Informed Practices.

Now the tips I write below assume that you are doing what you can to reduce harm. Remember in a world where most of our systems are built on exploitation, a “safe space” is never fully achievable — but a space where we can hold open dialogue, accountability, joy, rest, and healing is.

So after collaborating with some colleagues and researching, I’ve gathered some tips to help you centre the deeply impacted in your practice. Where needed, I found or made tools you can use and apply to your work.

These tools are new and experimental, so let us know how it goes if you try them out. You can use and modify the tools how you wish, as long as you don’t put them behind a paywall(2).

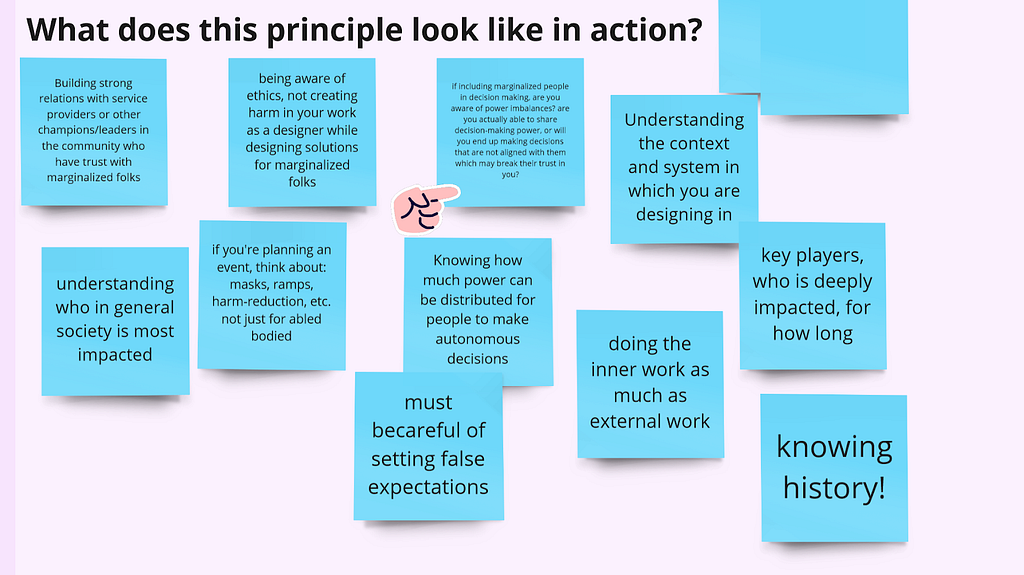

1. Build a deep understanding of power dynamics, inside and outside of work

Afro-Indigenous designer and artist, Anisa Matthews, says that to centre the deeply impacted it is about “doing the inner work as much as the external work”. Meaning that not only should we teach ourselves about the histories, identities, and systems of oppression that may appear in our projects, but also how they appear in our everyday lives.

Doing this can help us better understand what type of power dynamics may appear throughout our work and within our lives. Learning about identities and positionality takes a lifetime — we can never know all the intricacies that come with an individual’s or community’s identity, but we need to be open to listening, learning, and unlearning.

A specific tool that is a good beginner exercise to reflect on your own identity comes from researchers at the University of Toronto, Danielle Jacobson and Nida Mustafa. I suggest you read their paper on how to use it and if you’d like to try it out, you can use this template I recreated or print out. Past this, MIT put together a list of readings and exercises for facilitators and teachers that could help you reflect further.

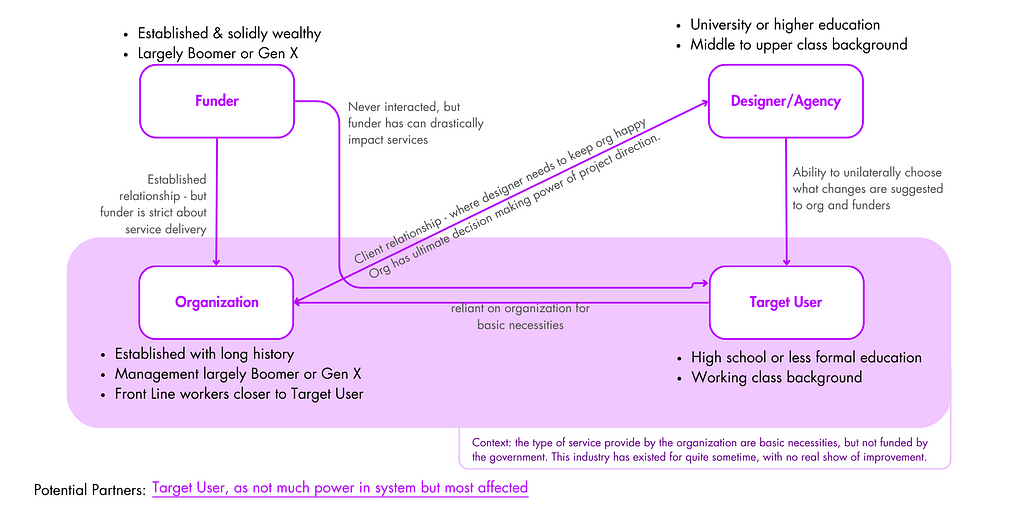

Now applying this tip to your projects, my friend Zoey Li from Button Inc helped me create a power-dynamic reflection map that could be used at the start of a project. It works similar to a stakeholder map, though with a deeper focus on existing power-dynamics.

Filling it out can be messy and difficult, but it should help make things more transparent and help you identify where and with who you need to focus your efforts. You can access a whiteboard template with instructions here and a printable version of the tool here.

2. Focus on relationship building and showing up for the communities you’re working with.

Trust is something that is earned and maintained. Meaning it’s time the “$25 gift card one-and-done” version of codesign comes to an end. Hopefully to be replaced with a process that includes community members as valued partners and co-creators.

I said this in my previous article about facilitation, but I really believe people have great solutions to their challenges — we just have to actually listen. But that is only the first step.

When we centre the deeply impacted, it is about showing up, supporting, advocating, building confidence, and connecting people to resources. It takes time to build trust, even sometimes years, but once established it helps you get better feedback, honest opinions, and deeper buy-in.

Now there is no one way to build a relationship, so it is hard to provide a tool for you to use. Instead, I want to provide some tactics I have found that have helped me and others in the past as well as provide some reflection questions.

First you could try:

- Finding someone who has built a trusted relationship with the community already and bring them on the team as a advocate. This is a great option when you are short on time or far away from the physical location you’re designing for.

- Showing up for the community you’re designing with. Beyond volunteering and ethnographic research: go to community events, listen to people, help out where you can.

- Taking the time to identify and convince potential roadblocks — often these are managers, funders, and the people who need to say “yes” to whatever you’re suggesting.

- For a more formal setting, creating a timeline of what this relationship will need at each step of the way. This should be done together with the stakeholders.

Some questions to reflect on are:

- Why do you want to design with this community? Do you have the time to collaborate respectfully?

- Who and how are you reaching out to be the community advocate? Are they in a vulnerable position where they may see you as a lifeline rather than a collaborator?

- If you have a community advocate, how are you supporting them? How are you reducing the harm they may encounter?

- Do you have the power and authority to implement the suggestions from the community? If not, how can you manage expectations?

- How are people, including leadership, accountable for their actions?

- Do you have the resources to do this project in a way that respects people’s decisions and needs?

3. Assess needs while being transparent about existing tensions, limitations, harms, and expectations.

This is about building transparent and open processes. We want to create documentation that can make invisible influences, like tensions and decision making power, visible. It will help us get a baseline understanding of what everyone’s needs are, the tensions that exist between them, and the limitations in how we navigate them.

The reality of social impact design is that it will take a lot of time and convincing to shift decision-making power. So we need to be honest with the communities we are working with about current processes, collaborating to manage expectations and strategies together.

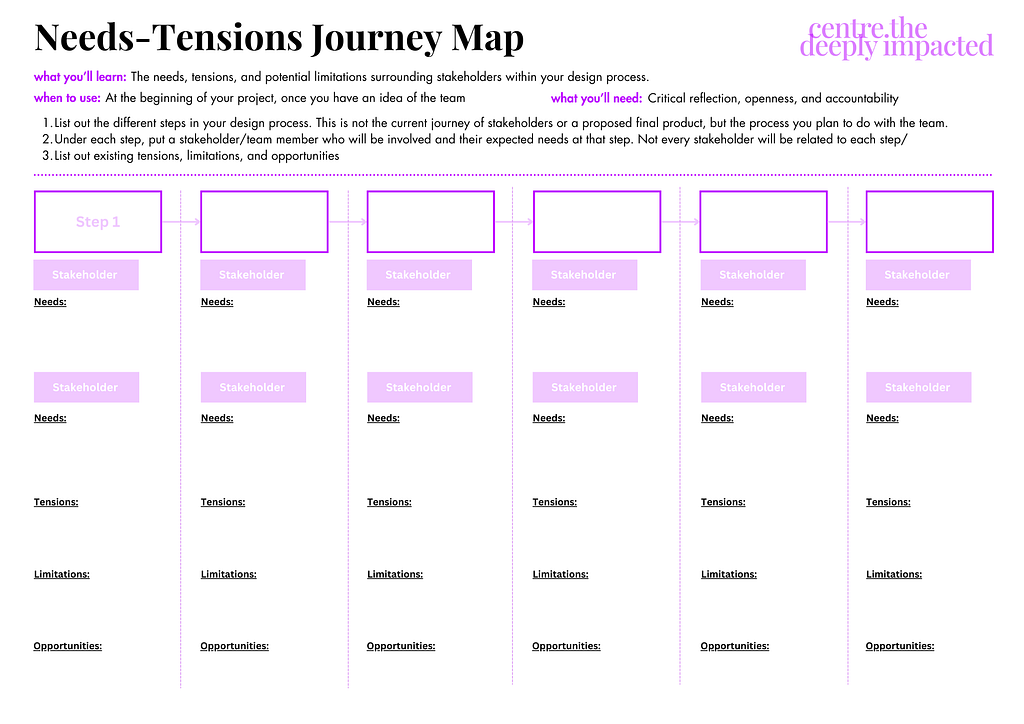

To help us start this transparency process, I made this tool I have dubbed the “Needs-Tensions Journey Map”. While a mouthful, it is to help you plan your design process with your team and highlight the parts in the journey where tensions may arise between stakeholders. It is important to note, this is not for a final project journey but about the collaboration process to get to said project.

Alongside the power-dynamic map, it can help pinpoint the different parts of the system where there is tension, potential for intervention, and who is actually being centered.

If you want to try it out, you can access a whiteboard template here and a printable version here.

Before you use this tool, I want to emphasize that you need to evaluate when, where, and with whom to use it. Highlighting tensions can be uncomfortable for everyone involved. And if people don’t have time to self-reflect or cannot accommodate uncomfortability, it can cause people to get defensive, shut down, or lash out.

But I believe if we aren’t open about the existing tensions, it is hard to manage them and strategize. So if you are planning to use this tool, assess first if the team you’re working with has the capacity to be honest, transparent, and accountable with each other. If you feel you aren’t in the position to do that, it may be best to skip this or just do it for your own reflection.

“Better” for the deeply impacted will take time…

…But it is possible if we are committed to collaborating in finding better ways to understand and show up for each other. Centring the deeply impacted can be seen as allyship, but to me, it is about seeing our struggles as connected, as something shared. That as Roxanne Gay quotes Ta Nahesi Coates in her 2016 article for Marie Claire, it is to “understand that you are not helping someone in a particular struggle; the fight is yours.”

And to those curious about exploring this fight to creating more equitable systems, I would encourage you to share your opinion and get involved in the ongoing collaborative refresh of Design for Collective Spaces (DCS).

DCS is a design approach that helps people in creating projects that care. Care about our planet, its people, and the joy that comes with working collectively towards a more equitable future… And is constantly evolving and refreshing with your feedback.

If you want to follow along, the easiest way to do so is to follow here and on LinkedIn. Where I will share inspiration, ask for opinions, and ask for your feedback here on our collective miro board.

The next principle in this series we are tackling is what it means to “reflect on our biases”. Giving myself a break over August, I plan to run some free online workshops throughout September where we can reflect on what this means and create ways we can integrate it in our work.

(1) This principle was originally: centre the most impacted. It was changed as “most” has a connotation of ranking and competition. While ranking is sometimes necessary, this principle is mainly about ensuring community members are part of and have more decision making power within teams.

(2) What constitutes a paywall would be if you are using the tools in workshops and courses that participants need to pay to attend. If you are a consultant wanting to use these tools with a client, please contact me so we can evaluate an equitable exchange.

Acknowledgments and thank yous

First and forever, a big thank you to the original team behind Design for Collective Spaces! Tracy Chen is an extremely talented product designer and visual artist who is currently working at Daybreak Studios. Eliza Lim is a detailed oriented and amazing design researcher at Samsung. Corrina Tang is a conscientious and utterly positive service designer for Code for Canada.

To Zoey Li who is so positive, inquisitive, and SUPPORTIVE when it comes to this project. In this article she went above and beyond with providing her perspective and edits. And I don’t think I could continue this project without you. Truly.

To Elodie and Jason for letting me read my article to you during our hang out sessions and both being so encouraging.

To Anisa Matthews who provided her thoughts on this and for always being able to recognize a good friend.

To everyone running and in the Impact Cohort by Distributed Design Platform, who were the catalyst for me starting this project.

Lastly, To Black, Indigenous, Trans, Queer, and Disabled activists who paved the way in social movements, care, and love. This discipline and how I approach it would not exist without these activists and writers.

I would encourage you to check out, read, and support the different people and projects I have referenced throughout this article.

Why not all voices should be equal in the design process was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply