Symptoms of this dysfunctional team strategy may include last-minute iterations and soul aches.

Recognizing systems and leveraging their dynamics to our advantage as designers.

Designers are well attuned to the way aesthetics, environment, and configurations can influence human behavior. The Norman door is a prime example. Famed and lauded in the design community, it is the quintessential illustration. A well-designed door offers simple features of discoverability, signals and affordances that cue the user of the door to push or pull on the left or right side. A/B testing is another well-known example, where designers can try out different visual arrangements on the website to coax users into preferred behaviors. However, designers and UX professionals often overlook the role of larger systems have on human behavior and decision-making.

The role of systems is often implicit or taken for granted. There are several reasons why. Systems thinking is difficult, and is often counter-intuitive to how we understand the world. Donella Meadows, author of “Systems Thinking: A Primer” not only expresses this point, but also what is at stake when the reality of this system is overlooked:

“The world is a complex, interconnected, finite, ecological — social — psychological — economic system. We treat it as if it were not, as if it were divisible, separable, simple, and infite. Our persistent intractable global problems arise directly from this mismatch.”

— Donella Meadows

Moreover, as this article will elucidate, the implications of systems thinking are sometimes unsavory, go against conventional wisdom, and pull us out of our comfort zone.

What exactly is meant by the word “system”? The quote from Donella Meadows above starts to get at its essence. Systems are much more than the familiar examples of machine, gizmos, and computers. Systems can be defined more generally as a set of things that works together as parts of a mechanisms or an interconnecting network. This means that even intangible entities like organizations, cultures, and societies can constitute a system just as much as machines and technology. They are an aggregate of interconnected parts, functioning in an interconnected network. Even trivial, daily tasks like snoozing the alarm clock, setting the temperature of your shower, or deciding when you should leave for work are mediated by unseen and complex systems in your life. These examples highlight a fundamental truth about systems: They are not just external to ourselves, we are a part of them. Systems rely on our own thoughts, expectations, and knowledge to use and interact with it. In his book “The Design of Everyday Things,” Don Norman, namesake of Norman doors, recognizes systems as internal and external to ourselves. He defines systems as knowledge in the world and knowledge in the head.

“Knowledge is both in the head and in the world… Because behavior can be guided by the combination of internal and external knowledge and constraints, people can minimize the amount of material they must learn, as well as the completeness, precision, accuracy, or depth of learning.”

— Don Norman

The Influence of Systems

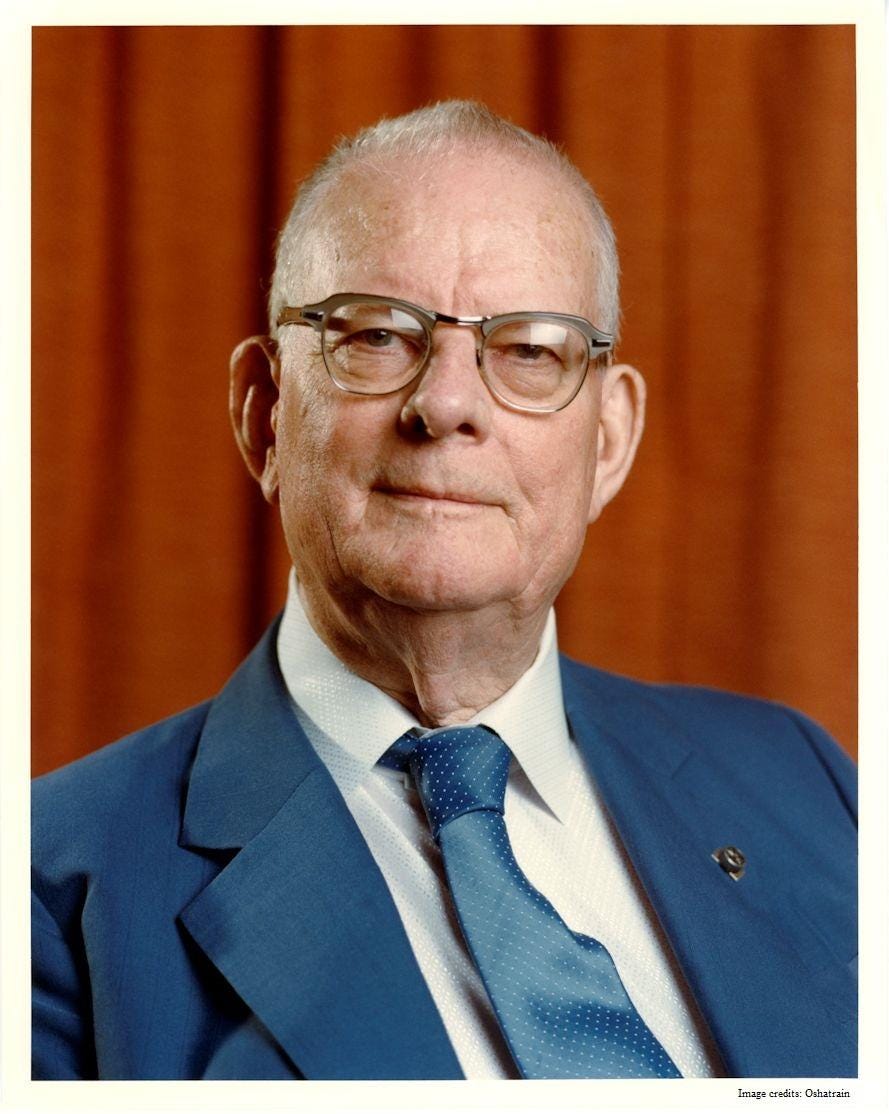

W. Edwards Deming, was a visionary force of industry in the 20th century. As a statistician, educator, and consultant, he shaped the modern landscape of American industry and helped a post-war Japan become the quality-obsessed, industrial juggernaut of the 1980s. Today, Deming is well-remembered for his impact in Japan, his use of statistics in business management, and the development of something called Total Quality Management.

Among the many things he is known for, one of the most important is his central belief in the power of systems and the importance of systems thinking. An idea best exemplified by an exercise he developed called The Red Bead Experiment.

The Red Bead Experiment.

The Deming Red Bead Experiment is an activity developed by W. Edwards Deming to illustrate the limitations of traditional management practices and the impact systems have on performance. The experiment involves a simple setup where participants, typically representing workers in an organization, are asked to perform a task involving red and white beads.

The Experiment:

The experiment requires a bowl filled with white and red beads. The white beads representing work performed correctly, and red beads representing a defective work product. Participants are instructed to use a paddle to draw beads out of the bowl, simulating a day’s worth of work. Their goal is to minimize the number of red beads in their work. After each round of bead scooping, participants’ performance is evaluated based on the number of red beads they produce.

Despite the participants’ best efforts to control the number of red beads produced, they find it nearly impossible to eliminate them completely. With each subsequent round, new incentive schemes are added from “management”. Management hopes that performance bonuses for no red beads and the threat of job eliminations will improve performance. However, despite the new motivations, the workers’ performance does not improve. They are constrained by the system.

As the experiment progresses to the final rounds, the best-performing workers (there are always workers that perform the best) are kept on, while the poorest performers are asked to have a seat (their job is eliminated). However, despite selecting the best, most talented workers, the production of red beads continues. The output is not improved. How come? The experiment demonstrates that outcomes, though they may fluctuate, are determined by the system. Blaming and incentivizing the human component of the system is counterproductive. It is a surprising and challenging lesson.

The Red Bead Experiment is a powerful metaphor for our own lives, both personal and professional. The experiment emphasizes the impact that systems have on individuals and their achievements. Put succinctly, for many activities it doesn’t matter how motivated you are, how much you care about your job, or how hard you try. You’re ability to achieve some goal will be supported or constrained by the capabilities and limitations of the system. Deming put it best: “A Bad system beats a good person every time, no contest.”

The experiment also yields critical lessons in leadership. If achievement and abilities are constrained by systems, the principal task of leaders is to assess the current capabilities of the system and find ways to loosen its constraints, in support and pursuit of higher levels of performance. This sentiment is echoed by Peter Senge in his seminal book, “The Fifth Discipline”:

“The neglected leadership role is the designer of the ship. No one has a more sweeping influence than the designer. What good does it do for the captain to say, “Turn starboard thirty degrees,” when the designer has built a rudder that will turn only to port, or which takes six hours to turn to starboard? It’s fruitless to be the leader in an organization that is poorly designed. Isn’t it interesting that so few managers think of the ship’s designer when they think of the leader’s role?”

— Peter Senge

Most people who are confronted with the lesson of the Red Bead Experiment have the same gut reaction. “That may be true for other people, or other work, but it doesn’t apply to me.” Everybody thinks they are the exception to this rule, but the truth is, nobody is. Systems are everywhere and they affect everything we do, how we do them, and how well we do them. This is true whether it’s drawing beads from a container or making important decisions. My task for the rest of this article is to convince you of this. Your task is to resist that gut reaction, let your guard down, and see whether there is some merit to the claim. If it’s not true, you can stop reading my articles and write me off as a hack. If it is true, however, then a fundamental reevaluation of priorities is merited. Taiichi Ohno, founder of the Toyota Production system, summarized the sentiment best.

“We are doomed to failure without a daily destruction of our various preconceptions.”

— Taiichi Ohno

System Dynamics

The main lesson of the red bead experiment is that systems dominate results; humans are merely role players within the larger system. The experiment also brings two features of systems to the forefront: variability and capability.

During the red bead experiment, the participants draw beads from the bowl and each time they do, a different number of red beads is produced. At first glance, this might feel like this is evidence against a system-dictated result. After all, if the system determined performance all of the workers should produce the same amount of white and red beads. The fact that there are differences between workers is evidence of their agency and impact on performance.

This intuition is wrong, however, in what is another cruel joke of systems dynamics. Just because a system limits and controls performance does not mean that the results will always be the same. In fact, this is a well-known phenomenon known as natural variation, common cause variation, or simply noise. Within the limits of the system, outputs will fluctuate, but they will never exceed the limits of the system. More often than not, when this principle is not appreciated it leads to “tampering,” over-activity to try and fine-tune the system beyond its capabilities. (Deming has another great experiment about this which warrants a separate article)

“Eighty-five percent of the reasons for failure are deficiencies in the systems and process rather than the employee. The role of management is to change the process rather than badgering individuals to do better.”

— W. Edwards Deming

Capability is what we can expect from the system both in terms of its limits and its regularity. Capability is the result of the operation of the system as well as the system’s design. For instance, healthcare may care about the patient wait times in the ER, the error rate of their surgeons, and their ability to collect payment from patients. All of these are dictated by the facilities of the hospital, as well as the caliber and practice of the hospital staff, clinical and non-clinical. Meanwhile, whether or not you are capable of getting up early in the morning to exercise with consistency is bounded, among other things, by the ease of use of the alarm clock snooze button.

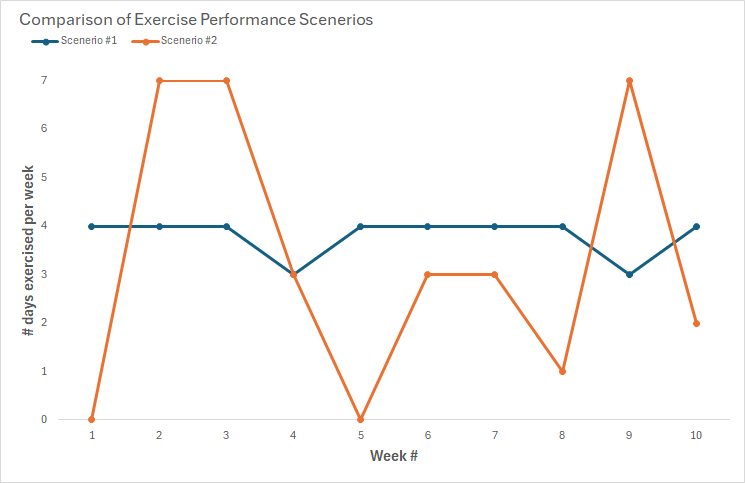

System capabilities are important because they provide expectations of what can be achieved, at both the high end and the low end. The spread between the high and low also tells us a good deal about the level of control human operators and decision makers have over the system. For instance, Consider two scenarios. In the first scenario I record 10 weeks of exercise and see that each week I got up before 6AM to exercise 3–4 times each week. In the second scenario, I record 10 weeks of exercise and see that some weeks I got up to exercise all 7 days, and other weeks I didn’t exercise at all. Which scenario is to be preferred?

It’s clear that the first scenario, where there is greater consistency demonstrates greater mastery of the system. Mind you, this scenario did not achieve the best demonstrated performance, but showed greater regularity and promises greater sustainability of the regimen as well as greater ease in elevating future performance (number of days per week).

The Role of Systems in Decision Making

Systems do not just have an overriding impact on human behaviors but also have an oversized impact on the way we frame problems, evaluate choices, and make decisions.

Carin-Isabel Knoop, Executive Director at Harvard Business School and founder of the medium site On Humans in the Digital Era, summarizes the point this way:

“We are all part of (living) systems. Systems shape us, and we impact the systems with which we interact. Systems engineering encourages a more holistic view of everything that impacts the employee upstream before problems occur versus dealing with potential distress or unhappiness downstream after problems have become apparent.”

One of the best demonstrations of the role of systems in human performance and decision making comes from the popular 2008 book “Nudge: Improving Decisions about health wealth, and happiness.” In the book, authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, two economists, discuss the impact of “context” in decision-making. Throughout the book, they make it clear that the way decisions are made has a lot more to do with the context and systems that surround the decision that the person’s own preferences or free will. They also prescribe that armed with awareness of this reality, we ought to engage in “choice architecture,” that is, designing the systems and contexts of decisions to influence outcomes. The book is chalk full of quotes that testify to the reality of the impact systems have on human behavior, including decision making. Here are just a few:

“People have a strong tendency to go along with the status quo or default option.”

“First, never underestimate the power of inertia. Second, that power can be harnessed.”

“The first misconception is that it is possible to avoid influencing people’s choices.”

— Richard Thaler

I will leave it to you to make your own moral, ethical, and practical evaluations of their proposals. Their main point, however, is direly important: behavior is impacted by systems.

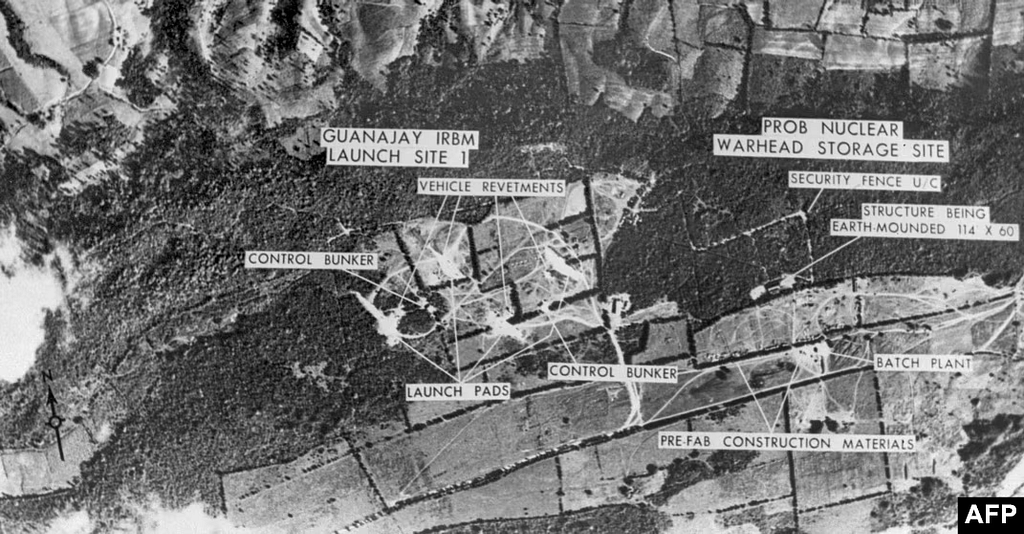

Likewise, in their book “Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis” Harvard Professor of Government, Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow, a US diplomat, use the Cuban Missile Crisis as a case study to explore how people make decisions. Their conclusion is to reject a simplistic explanation of Kennedy and Khrushchev squaring off as two rational actors in favor of a holistic systems view. One of their counterproposals to the rational actor model (RAM), is to look at the organizational behavior of both the Soviets and the Americans. The organizational paradigm they set forth is akin to the way we’ve been discussing systems. It provides a context for explaining how actions of organizations can be seen as an output of the organizational system. Like any system, an organization is composed of organizational actors, objectives, capacities, cultures, standard operating procedures, feedback norms, risk tolerances, response to change, organizational memory, and means of coordination and control.

Their analysis goes on to explain how the systems of international treaties, diplomacy, bureaucracy provide exceptional explanatory value that RAM leaves unexplained. To demonstrate the force of their analysis, consider several aspects of the Soviet effort in Cuba:

1) The USSR didn’t coordinate their air defenses with delivery of missiles.

2) The Cuban missile construction sites were not camouflaged.

3) The USSR did not try to expedite construction of the Missiles but operated at a normal pace.

4) The missile sites were identical to those in the Soviet Union, making them easier to detect.

These anomalies cannot be explained by any rational decision-maker but are manifestations of greater systemic forces, behaviors, and decisions. They are outputs of a rigid system, unaware of itself and unresponsive to change. Without any appreciation of its capabilities or limits, the Soviets relied on their internal systems and organizational knowledge to deploy and assemble the Missiles in Cuba. The Soviets did not coordinate the missiles with air defense systems because these were two separate military divisions and was never required behind the iron curtain. The same can be said for expediting construction and employing camouflage. The Cuban missile silos probably should have looked different since their strategic role of aggression rather than deterrence had changed. Organizations come complete with their own systems of logic and culture which bind behaviors and decisions. With greater appreciation of their reliance on systems the Soviet Union might have won the Cuban Missile Crisis, and our world may look very different today.

The faux pas of the Soviets during the Cuban Missile Crisis is a prominent example of the power of systems to impact behavior and decision making, as is the main thesis of economists Sunstein and Thaler. We do not make our decisions in a vacuum. This is neither a good thing nor a bad thing. Our interaction with the environs and systems around us constrain and limit our decisions and behaviors. With this awareness, we give ourselves greater personal and individual agency. Whether it’s to guide societies into making better decisions through choice architecture or leverage our own interactions with systems and environments to do more.

The impact of systems is often lost on us, not because we are stupid or obtuse, but simply because we are not used to thinking about them. Indeed, we are programmed to not notice such things.

The presence of cognitive shortcuts, heuristics, makes it easy for us to make decisions that are “good enough” and don’t require excessive cognitive strain. Yet, by looking past these shortcuts and truly appreciating the intricacies and permeabilities of systems all around us, we see the stark reality: we are buffeted about by systems.

This realization is an opportunity. Any insights gleaned through this paradigm will likely yield never-before tried approaches to common, pervasive problems. And what’s more, there are lots of low hanging fruit.

By recognizing systems, we can find ways to leverage their dynamics to our advantage, making the most of our efforts, decreasing our cognitive loads, and increasing our productivity.

The role of systems in decision making was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply