Learn how El Retiro in Madrid applies UX to transform its green spaces into one of the best places on Earth.

Business as usual? No.

Three years ago, during the hard Covid lockdown in The Netherlands, the news arrived at our company; we were going to be acquired by a competitor. At that point, my reference to company acquisitions was Meta buying Instagram or movies depicting evil corporations pushing local shops into bankruptcy. I had no idea how common mergers and acquisitions are all around the world, across many industries. Naturally, questions piled up in my mind: Will I still have a job? Will my colleagues still be around? Will I be replaced by their own designers? Will we lose all the hard work we’ve put to get the product where it was?

It took me a few years to look back at what happened during this acquisition journey, objectively; the way it affected me as an individual and as designer, and the way it shaped the emerging organisation. Here are a few reflections during that process, and a few things I would’ve done differently that may help others experiencing this.

Business as usual? No.

It all started on the wrong foot. I’ve severely underestimated the importance of this change, trying to ignore it as much as possible. In the end, the company went through acquisitions before I got there, and it looked like they did just fine. Why bother then? I’ve kept my focus on ongoing projects, peeking out behind my laptop to listen to a few announcements, assuming we’ll get an email or two, and nobody will bother us anymore.

As one might expect, the first to be affected were executives and senior management. These higher-up role changes used to sound like a high stakes version of musical chairs to me, hoping that the people I know will still be around by the time the music stops. Instead of disregarding this, just looking into the new reporting structures could’ve helped me get a sense of mid-long term focus in the organisation. Luckily, my ignorance was only followed by a positive surprise, since things changed for the better. In the past, engineers, data analysts and designers were all mixed and mashed at the leadership level. As a result of the acquisition, each function got individual leaders with specialised expertise, thus roles had better representation on higher level, scaled accordingly, with unique approaches for career paths. Imagine a less positive scenario though, in which design is given less presence in the company at leadership level. Looking at other functions that experienced this, it would’ve affected my freedom to take on initiatives, my involvement in strategic discussions and ultimately my growth.

There’s acquisition bias in decision-making

Since we were competitors before the acquisition, their main product (an app) has been analysed several times in the past, discovering both great and terrible features. Using a mix of frameworks, open data and comparative user studies, the consensus was that their consumer-facing experience was falling behind. The acquisition added a layer of subjectivity to this conclusion. It only took a couple of months to notice a change in some people’s attitudes, with strong or even harsh views softening up. Suddenly, some of their solutions didn’t seem so bad anymore, with negative things becoming interesting. I fell into a confirmation bubble too, being biased by this growing shift in mindset, mostly focusing on positives.

Not clarifying this bias early on, made it difficult to find joint solutions later, and it did not feel right, knowing deep down that we’re avoiding tough conversations. Unfortunately I did not find a way to surface these observations to the larger audience, without overcoming my fear of polarising them, having to facilitate discussions at a level I wasn’t comfortable with, back then. This is perhaps one of my biggest shortcomings during the entire process, since I ended up following the majority far too many times. I believe I could’ve made my point clear more often and avoid issues coming later, with way more complexity.

As obvious as it may sound, data provides the best argument in these cases, not only to guide an objective path forward. I could’ve tried to combine as many sources of knowledge as possible, e.g. sales numbers, customer care topics, dug out those qualitative user research findings, market analyses, or just blame the process and say it’ll all be done later by others. Unfortunately, what I noticed is that if very little data is involved, there is a risk important decisions will be heavily driven by biased arguments, by a majority or by politics building to please the new organisation, rather than users’ needs.

Identify opportunities and balance out busy work

The behaviour that surprised me the most was not resistance to change, rather instant embrace. I found it odd to see people quickly ditching past initiatives and plans, to accommodate whatever vision the new group has. The truth is that some people will feel their role is redundant, and they’ll try to get themselves visible with every little opportunity, no matter how small or big of a task they pick up. This resulted in a bunch of busy work flying in from a bunch of new directions, many landing on my table. Requests like updating presentations to match a new styleguide, supporting marketing teams efforts, replacing assets in flows, using new templates for files, did not feel like a priority to me, while we were ongoing large organisational changes. Eventually, they did contribute to a feeling of unity, but could’ve been done at any time. Getting an influx of work during times like this is natural and simply pushing back until you find just the right type of project isn’t realistic. It’s more about finding a balance between low and high impact work, and honestly it’s also fun to get out of the usual pace and try out some new things. While you make sure you don’t stop other’s momentum, you should also figure out how to contribute to bigger goals. Luckily, in my case, I had enough support to keep a healthy mix of small tasks while supporting broader questions affecting real user challenges.

One aspect, which I wrongly classified as busy work in the beginning was collaborating with people outside of my immediate reach. I kept hearing people from sales, customer care, or marketing trying to communicate needs they identified as important to the rest of the company. Honestly, helping them felt like an uphill battle in the beginning, at times wondering whether putting effort in translating their data and terminology into user needs was worth it. In the end, working together to express their concerns brought up critical aspects in the user experience that we would’ve missed otherwise. It also resulted in an opportunity for me to work on higher level user journeys across teams and functions, something that didn’t happen regularly before.

Get a sense of values and maturity

This is an obvious one, but I can’t stress enough how big of an impact it had on my mental health, in the long term. Treating an organisational event of this magnitude almost like a new job might sound like a hassle, but also forced me to take a decision: commit to stay or move on. I stayed, not fully convinced in the beginning, but willing to give it a try and see what they’re all about. However, understanding values, intricate ways of working or cultural changes seemed boring. I was already imagining scenarios in which I’m swooshing in with my amazing skills, presenting mind blowing solutions, improving every user flow out there within a month. Once again, I was wrong.

It was quite difficult to get past my initial skepticism and find a way to relate to broad, company values in a practical sense. I realised after a while, that it’s not only about the words and materials used to express these, but more about their adoption. If a company manages to inspire people to adopt high level values in their daily work, in their own individual way, it’s doing something right. Obviously, values themselves sounded good too.

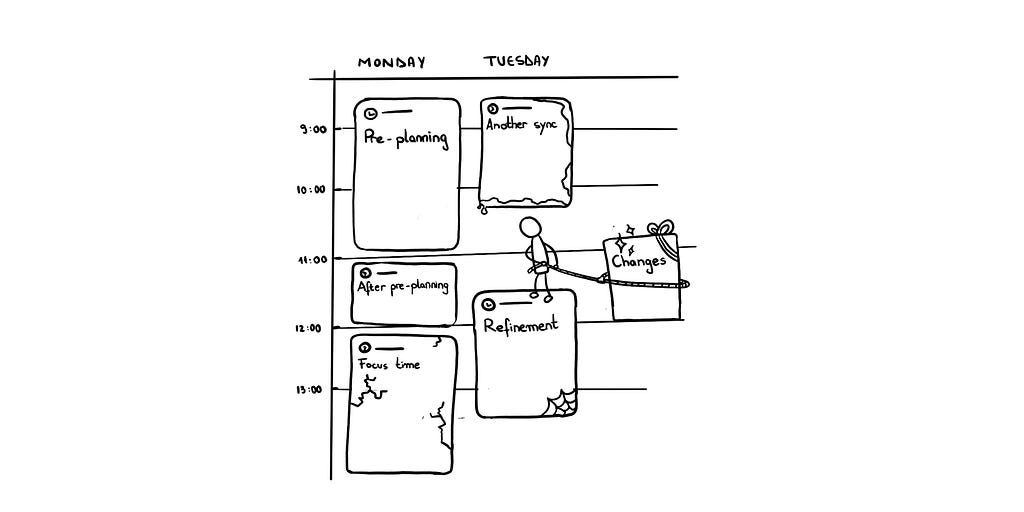

Getting a feeling of culture was next. I decided that the best way to capture this was to stop daydreaming and take more concrete actions. First, participate in everyday ceremonies to observe dynamics between functions with a focus on designers’ collaboration with developers and managers. The second thing was to get involved in ongoing projects to get a sense of the way teams approach complex problems. Do they have the experience and processes to react in a calculated manner to find great solutions, or do they mostly adopt quick and dirty workarounds, and move on? Do they have a support structure that enables decision taking, or do they rely on whoever gets to talk the most in a meeting?

The hope was that by putting it all together I’d be able to understand whether the bigger organisation was projecting a false image into the world, hiding behind buzz words. Again, luckily, I discovered a company that was well intended, transforming, but still had a lot of work to match their image. Throughout this process, I also learned that the new company was less mature in adopting product development and design processes, but they committed to improving this moving forward. Another question was forming in the back of my mind: I can work with this, but am I willing to spend the next years going through similar pains just to reach the same level of maturity? Or is it time to move to a place with these things already in order? I decided to stay and do things again, but better this time around.

Speculate, but move on

There are aspects of an acquisition that cannot be made public until the process is finalised: employee contracts, new roles, shifts in product strategy, overall brand changes, etc. There are usually clear guidelines what the company can and cannot answer in advance, but since we are human, part of our natural instinct is to speculate and find explanations if we’re not given one. What I noticed is people who spend too much time trying to guess what will happen tend to adopt a pessimistic attitude towards work, in general. For them, putting effort into current initiatives doesn’t seem to make sense anymore, since “who knows what will happen anyway”. What worked for me was to listen to these conversations as I would listen to users, looking into nuances, words and attitudes to figure out who was willing to put the effort and adapt to changes. It’s toxic to sit in a group that constantly speculates, is cynical or creates drama. Try to move away from them. In the end they didn’t only negatively influence the quality of my work, but also drained my energy.

Present the work, not yourself.

There’s a point in an acquisition when people move from experiencing the others’ product as a user, to getting an in depth internal view of how the product really works and performs. A big part of my work back then was presenting product flows, insights and opportunities to their teams. Since our problem spaces were similar, you can imagine so were some of our solutions. In my mind, the solutions I’ve contributed to were great, assuming we’ll just move on, exchange some knowledge, and get to ship things right away. I realised after a while, that even though people were showing a genuine interest in learning about my approach, it took weeks of repeating the same data points in different contexts, to get knowledge to stick. At that point, I started doubting both the solutions and my story telling skills — why aren’t they mesmerised? why aren’t they just dropping their work and adopting my ideas? why aren’t we developing this already???

First, it would’ve been be a better approach to gradually introduce new information rather than show an avalanche of artefacts right away. Sending a bunch of links to lengthy reports and design files with hundreds of screens had the adverse effect. People did have other things to work on as well. Looking back, it’s almost embarrassingly obvious how much I was trying to push my own agenda, trying to back it up with tons of references. Perhaps it’s a natural response to the whole feeling of being acquired, but it also surfaces areas in my self-confidence that I need to improve on.

Most questions during presentations were more about metrics and impact on users, and less about solutions’ details, definitely less about how I got to those solutions. Sometimes, I’ve worried too much to make my individual contribution visible, getting lost in presenting sketches, wireframes, diverging and converging throughout the process, losing the audience on the way. I could’ve learned way more about their focus, earlier on, and then figure out where do I want to bring in value. It seems obvious saying this now, but instead of throwing everything and hoping that something sticks, get people curious with concise insights and strong, validated statements, to begin with. This will make it easier for everyone to quickly understand the value your work can bring to current user problems you’re all trying to solve for.

Have a backup plan

No matter how transparent this process is, acquisitions can quickly become volatile. It could be something that wasn’t considered properly before, which results in budget cuts, or decisions on which features to keep maintaining. It could also be someone leaving and destabilising teams as well, everyone goes through their own judgment process, they might not like the change and leave. Eventually I got to enjoy this process , since I finally had a good reason to recap all the projects I’ve contributed to, figuring out how to document these in my portfolio. It’s always surprising to see how much you’ve done in the past, ideally without dwelling too long in the feeling of nostalgia. Then, I’ve spent a bit of time to get a sense of the job market in the design world and reflect on what would be a next step, just in case. Moreover, I realised that there’s no immediate guarantee that my career ambitions will be fulfilled in the new organisation. It was unlikely that someone would shut off opportunities for designers out of the blue, but as mentioned before, designer’s responsibilities can be wildly different in between companies, e.g. what if I don’t have the same freedom to conduct user research, and I’m expected to focus a lot more on supporting devs to create UIs? It doesn’t necessarily mean the approach can’t be changed, but the starting point will be different.

Design is difficult to merge

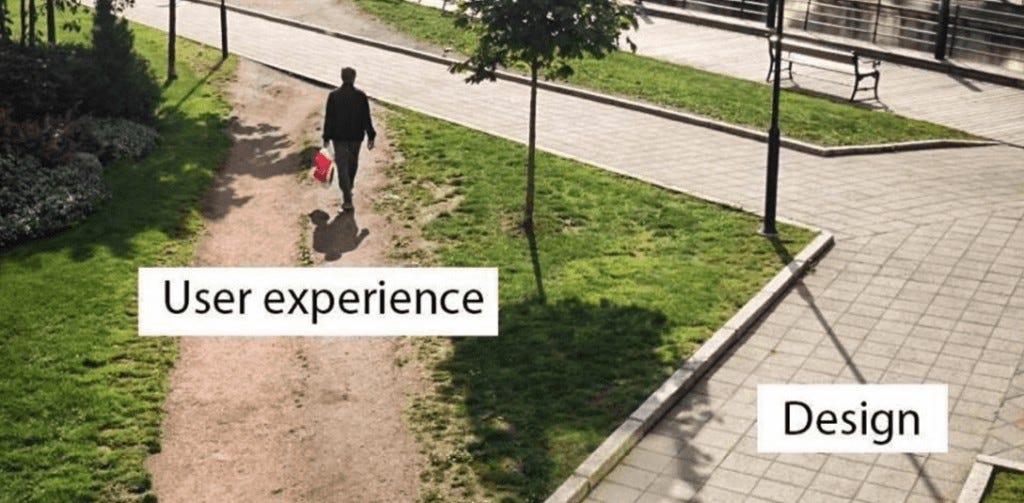

Building any kind of team means matching people on multiple levels, as skill, seniority, personality traits, specialisation, with the list going on for a few more rows. Having a cohesive team requires time and strong leadership that can identify what kind of gaps need to be filled based on present and future needs. Well, an acquisition might just ignore all that. In my case, both design teams were understaffed which lead to simply merging us all together, honestly, just hoping for the best. On top of that, each team had taken quite different approaches to their role in the company. One mostly busy creating UIs, trying to question tasks given to them by managers and engineers, while the other was transitioning to supporting discovery processes, scoping out work earlier on and relying more on design systems for decision-making. Merging was not straightforward. Each team had their pains to address, vision for ways of working, ideal structure, roles to add, tooling to buy, collaboration models to try out. How do you bring all these things together with as little friction as possible?

What I noticed is that top-down decisions tend to help in this situation, especially around team structure and roles, offering a foundation to build on; a foundation that provides enough freedom to try things, while having clear constraints. Generally, having a leader with a strong vision in a newly formed design group is needed, to expedite some decisions. The alternative is analysing endless possibilities framed as conversations instead of actions, which I unfortunately experienced until our group did get a leader. It all happened just in time to get going. There is a period of figuring things out during an acquisition, but sooner or later you need to get things done. You do not want to be in a position of still discussing basics ways of working in your team, by the time new projects get started. Looking back, I see that instead of pushing so hard for my own perspective of how the team should work, I could have helped create a stronger, more cohesive group and then push together in the same direction. Thankfully, due to everyone putting effort in this collaborative process, things worked out quite well, but it took a long time to figure it all out. If we were to start a design team from scratch, would it be formed by the same type of people? Not sure…but I’m happy to have experienced this process.

Embrace it, or not.

It’s tough to be acquired, things change and change in itself is difficult to deal with. No matter what you read and how many opportunities might come up, there is an emotional aspect to an acquisition that should not be ignored. However, dwelling on what was, and what could’ve been isn’t healthy either and constantly referring to the past will wear you down together with whatever passion you’ve got left for design.

Ignoring the change will eventually mostly get back to you because you missed the opportunity to influence it, and woke up by the time it’s all done. Pushing back on decisions by then will not only be difficult, but most likely out of sync with everyone else’s focus. Take time in your busy calendar early on, get informed and try to understand what this process means for you. Stay if you think there’s something worth building upon, or simply move on to try something else.

How did a company acquisition feel like for a product designer was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply