In the battle against misinformation, the solution lies in greater transparency, not censorship.

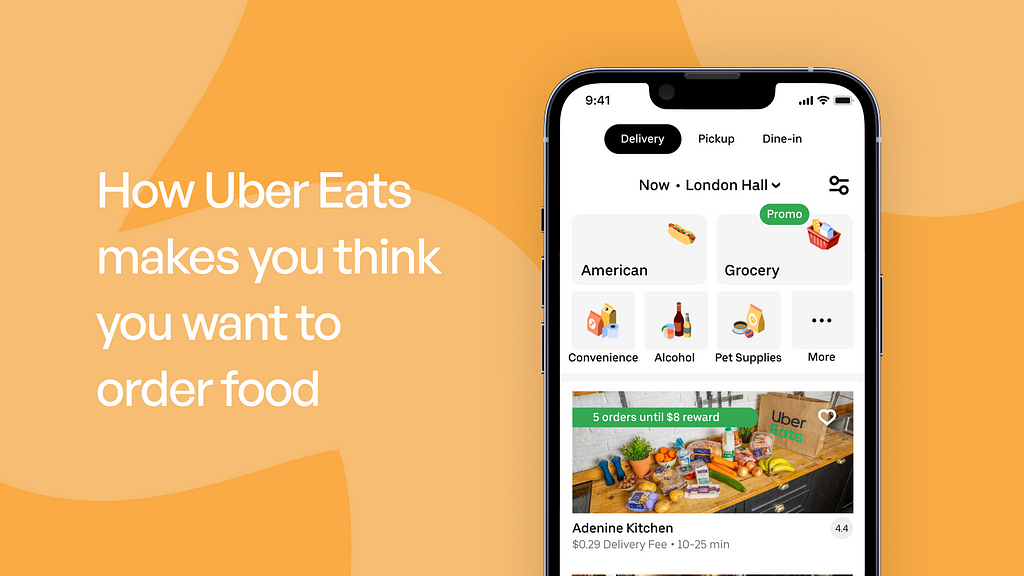

Apps like Uber Eats aren’t just about convenience; they’re designed to make food delivery a habit you don’t even think about.

Did you ever order food with the Uber Eats app? I certainly have — and I bet I’m not the only one.

Let’s tart with our current reality. Even though Uber Eats is here for a while now, last month (August 2024) nearly 30,000 people downloaded the Uber Eats app in my home country (The Netherlands).

However, we don’t want to rely on food delivery apps. After all, our kitchens exist for a reason, right? Yet, Uber Eats has a different goal. They don’t want you to order food as a special treat every now and then — they want it to become your default.

Apps like Uber Eats aren’t just about convenience; they’re designed to make food delivery a habit you don’t even think about.

But Max, I can decide for myself if I want to order Uber Eats tonight. — Are you sure? Or did Uber eats influenced your decision-making? Let’s find out!

Convenience is Uber Eats’ biggest ally, and let’s be real — we humans love convenience. We want things to be easy.

But forming a habit doesn’t come easy. Think about how hard it is to stick to a new habit (e.g. walking 10.000 steps everyday). If developing habits is tough, how does Uber Eats get so many people to use their app regularly?

Now, I don’t want you to feel bad about using Uber Eats. As with any behavior, it’s up to you to decide when it aligns with your values and goals. Convenience can definitely be worth it.

That said, it’s still worth to discover when behavior is actually triggered by our own goals and when it might be influenced by others!

Personally, I love using behavioral models and frameworks to design and analyze how digital products shape our behavior. However, it’s crucial to recognize their dual nature:

- Enhancing user experience and promoting “healthy” habits

- Creating addictive products that may harm society

For example, experts often argue that the way social media’s short-form content is designed shortens children’s attention spans.

Given these potential risks, designers should approach behavioral models with caution and ethical consideration.

Today we’ll use the Hook Model from Nir Eyal, a psychological framework that explains how products should be designed to form habits. It breaks down into four phases: Trigger, Action, Variable Reward, and Investment.

Let’s explore how Uber Eats makes us choose convenience — and order food over and over again.

Triggers: how Uber Eats initiates your behavior

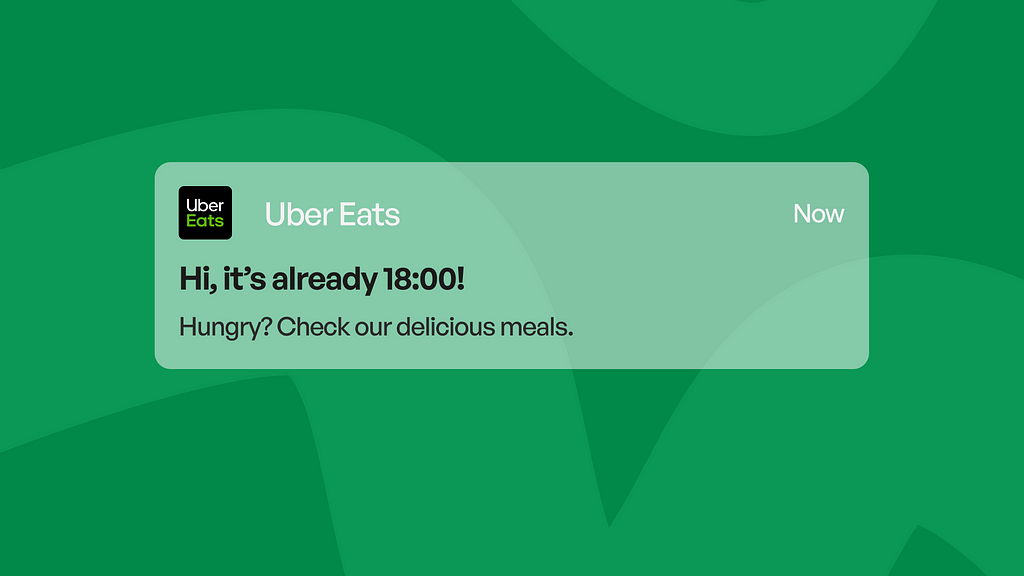

A new habit starts with a recurring trigger — a cue that prompts the user to take action.

Triggers can be external (notifications, prompts) or internal (emotions, desires). Uber Eats relies heavily on external triggers in the form of app notifications, promotional offers, and reminders. These cues are strategically timed to coincide with moments when users are most susceptible to ordering food.

Imagine it’s 7 PM, and you’ve just finished a long day at work. You’re tired, and the last thing you want to do is cook. Suddenly, your phone buzzes with a notification from Uber Eats — 15% off your favorite restaurant. Do you resist, or do you hit “order” without thinking twice?

Research in behavioral psychology suggests that timely external triggers can be highly effective in prompting action, especially when they coincide with internal states such as fatigue or hunger. By aligning external triggers with internal motivations, Uber Eats maximizes the likelihood of engagement.

Action: ordering food without a hassle

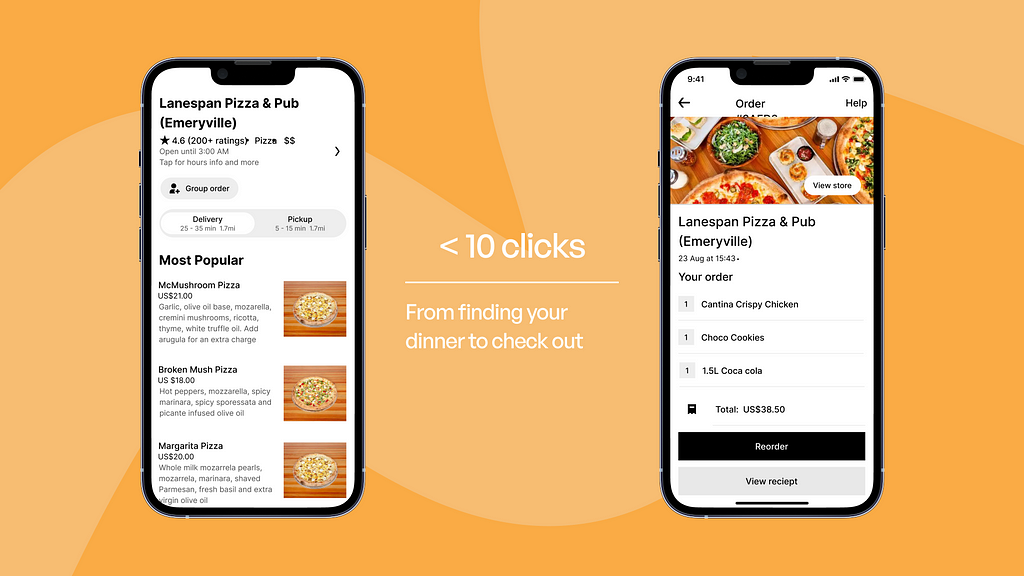

After the trigger, the next phase in the Hook Model is action. This phase refers to the user performing the simplest behavior in anticipation of a reward.

According to the Fogg Behavior Model from Dr. Fogg, action occurs when motivation, ability, and a trigger converge. If Uber Eats wants us to order food, they need to make the desired action — placing an order — as effortless as possible.

Reducing friction and simplifying the ordering process is key. — Only then you’ll always feel able to complete the action. In this case, ordering your food.

The app’s design prioritizes ease of use. With saved payment details, preset delivery addresses, and user-friendly navigation, the process of ordering food is streamlined.

At any time you’ll know you’re just a few clicks away from your next meal. Sounds easy, right?

Research shows that minimizing cognitive load — the mental effort an action costs is critical in driving repeated behavior. By making it incredibly simple for users to order food in just a few taps, Uber Eats eliminates any barriers that might prevent users from completing their orders.

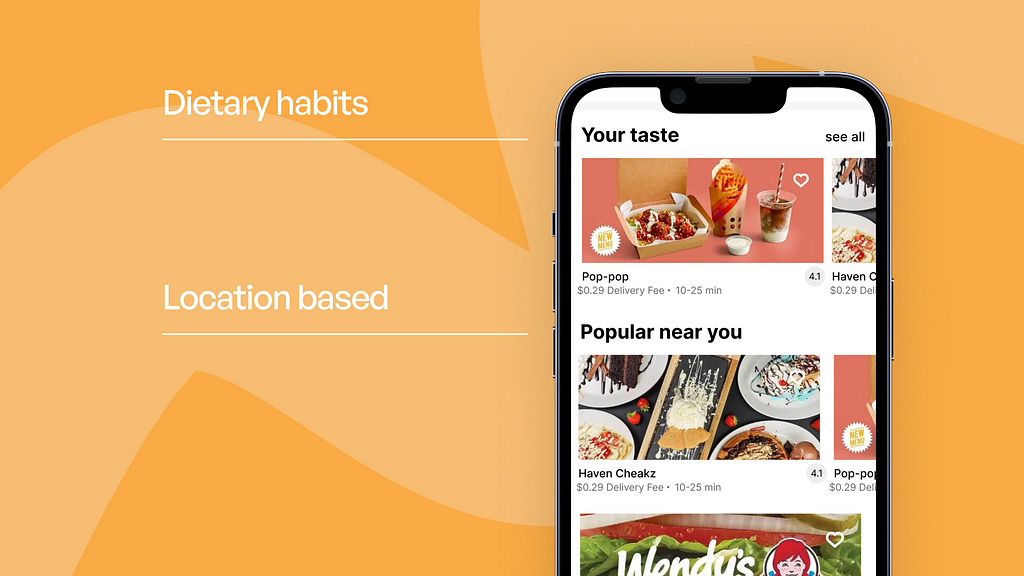

Another common challenge in apps like Uber Eats is decision fatigue — the mental exhaustion that comes from being presented with too many choices.

Ever found yourself looking for a movie on Netflix for a bit longer then you anticipated?

Instead of getting lost in endless scrolling, users are presented with personalized suggestions based on their previous orders, dietary habits, location, and time of day. Ultimately, making the decision to decide what to eat feel intuitive and easy.

Variable rewards: an offer you can’t refuse!

The concept of variable rewards taps into one of the most powerful principles in behavioral psychology: the unpredictability of outcomes. In 1963, the famous psychologist B.F. Skinner published his article about operant conditioning and intermittent reinforcement. Explaining how rewarding behavior sporadically and unpredictably creates expectations and excitement in humans.

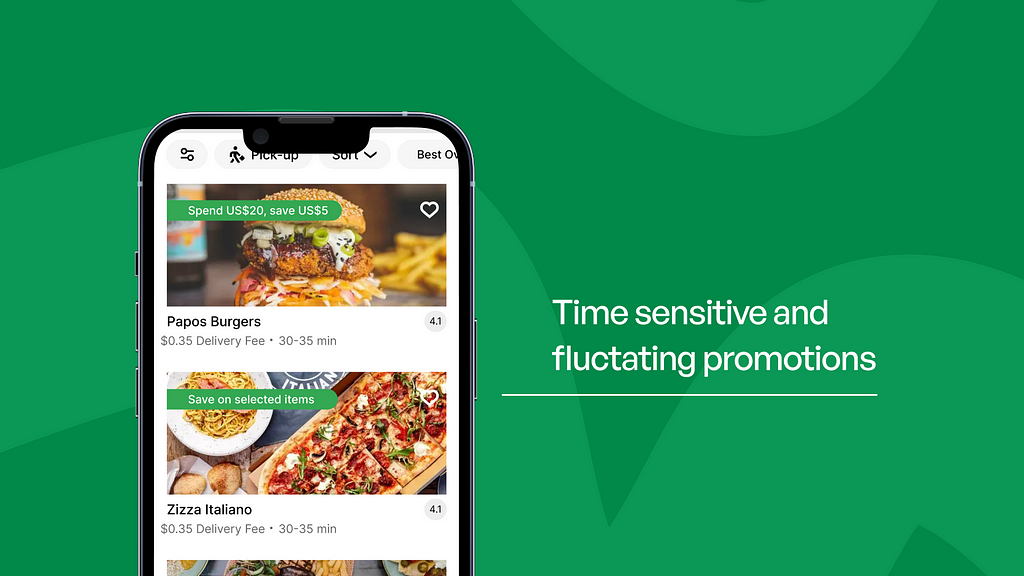

In the context of Uber Eats, variable rewards come in the form of fluctuating promotions and discounts. Users are often presented with time-sensitive offers, ranging from percentage discounts on their favorite foods to free delivery. But why do they work so well?

When users experience unexpected rewards, their brains release dopamine, a neurotransmitter tied to craving and reinforcement. This surge of dopamine creates a positive association with the action that led to the reward, such as ordering food through Uber Eats.

Unexpected rewards create positive associations with the action that led to the reward.

Over time, this reinforces the behavior, making users more likely to engage again. The unpredictability of these rewards adds an extra layer of anticipation and excitement, keeping users curious about what they might receive next.

This blend of dopamine release and the thrill of unpredictability compels you to return frequently. Does that sound like the development of a habit?

Investment: building long-term commitment

The final phase of the Hook Model is investment, where users contribute something valuable — time, effort, or personal data — that strengthens their commitment to the product.

Behavioral research suggests that when users invest in a product, they are more likely to return to it, as personal investment creates a sense of psychological ownership.

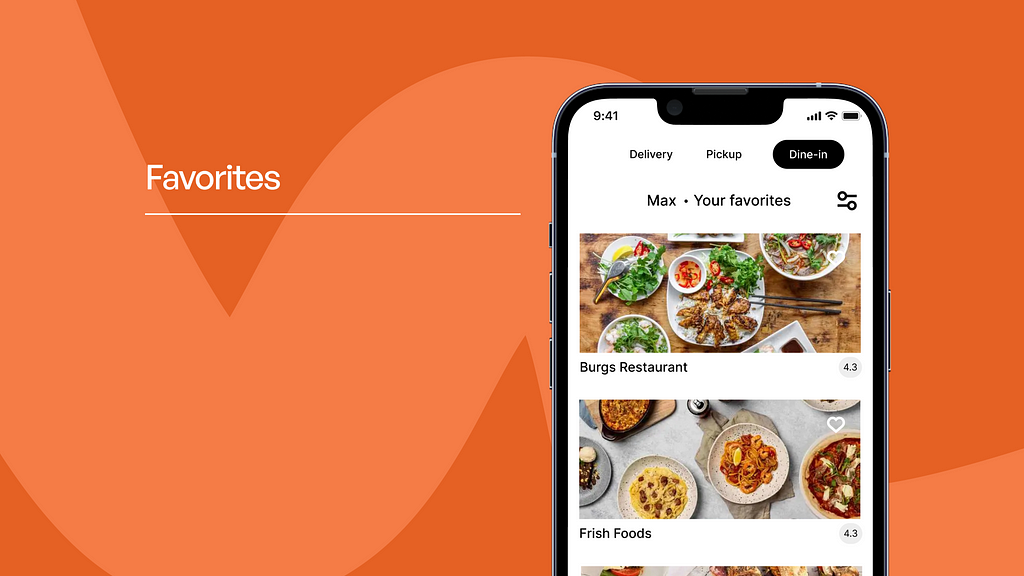

Uber Eats encourages users to invest by offering features that allow for personalization.

Users can save their favorite restaurants and customize their preferences. Each time a user adds a restaurant to their favorites list or they are investing in the app, which increases the likelihood of future engagement.

Writing a review is not just a personal investment — it enhances the overall value of the product and user experience. Each time someone leaves a review, it benefits other users by providing valuable insights, making the app more useful and trustworthy for everyone.

Great investments actually improve the overall value of the product.

Moreover, gradual investment is key. Uber Eats doesn’t rely on large, one-time actions. Instead, small, consistent investments — like adding restaurants to a favorites list or writing reviews — build up over time.

Conclusion: design impacts our behavior

The next time you order from Uber Eats, remember — it’s not just about the food. It’s digital technology that’s been carefully designed to keep you coming back. Through triggers, simple actions, variable rewards, and investment, Uber Eats has mastered the art of habit formation.

It’s fascinating to see how digital products shape our behavior, often without us even realizing it. Behavioral psychology might sound complicated, but it’s being used all around us, influencing the decisions we make every day.

So, if you find yourself on the Uber eats app again, think a moment about how you ended up opening the app.

One more question

As digital products continue to shape our habits, how aware are you of the psychology behind the apps you use? And more importantly, how much control do you feel you have over your own habits?

Sources used:

- Statistic: Monthly downloads of the Uber Eats app in the Netherlands from January 2020 to August 2024

- Medium article: 21 UX strategies to maximize user engagement without exploitation

- Science article: TikTok Brain: Can We Save Children’s Attention Spans?

- The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps

- The Fogg Behavior model

- Niels Norman Group: Cognitive load

- Medium Article: Decision fatigue and user experience

- Scientific paper: Operant behavior by Skinner

- Medium article: The Psychology Behind Variable Rewards

- Scientific paper: Consumer Psychological Ownership of Digital Technology

How Uber Eats makes you think you want to order food was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Leave a Reply